“When I say, ‘Sandy Hook,’ what does that mean to you?”

The question, posed by Utah Valley Hospital nurse Tina Dewey, is an unusual way to kick off a first-aid class.

But the threat of gun violence is what’s motivating scores of Utahns to sign up for “Stop the Bleed” classes being offered by health care providers around the state.

“With all the events going on in the news lately, we figured it would be good to have just some basic knowledge of things like first aid,” said Niles Wimber, who signed up for an upcoming class with his wife, Svetlana. “This is seemingly more and more — like, I hate to say popular, that’s pretty morbid, but it almost seems that way.”

The Wimbers’ summer schedule is packed with festivals and fairs, and increasingly, Wimber said, he finds himself envisioning how a shooting or bombing might play out.

“We were just at the Lantern Fest in Tooele,” he said. “The main area was enclosed by a chain link fence and there was one large entrance. If something were to happen there wouldn’t be a whole a lot of options.”

Wimber, of Provo, has no background in health care; he is an IT specialist at Utah Valley University. But, he says, if he’s at a big gathering and the worst happens, he’d like to be of use.

“People are energized to learn these skills,” said Zach Robinson, outreach coordinator for University of Utah Health’s trauma program, which is one of several Utah organizations offering the classes. “They’ll leave a class really excited, feeling like they can help.”

At Utah Valley Hospital in Provo, which specifically advertised its classes as preparation for mass shootings, enrollment spikes after high-profile shootings are in the news, said trauma surgeon Mark Stevens.

“I couldn’t keep up with class requests after Las Vegas,” Robinson agreed. “We were doing classes like crazy.”

A gunman opened fire on the Route 91 Harvest music festival on the Las Vegas Strip in October, killing 58 people and injuring 851.

Recently, requests have come in from youth organizations, like Boy Scout troops and schools, he said. Teachers at Beacon Heights elementary school were trained last month following months of national debate and escalating fears after the February shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla.

The principal “wanted us to specifically come and talk to her teachers because of what’s going on in the schools,” Robinson said.

The Stop the Bleed campaign grew out of studies following the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Connecticut, where 20 students ages 6 and 7 were killed, as well as six adult staff members. Doctors at Hartford Hospital examined the role of blood loss in the deaths and began to campaign for more immediate, aggressive efforts to staunch bleeding in events with mass casualties.

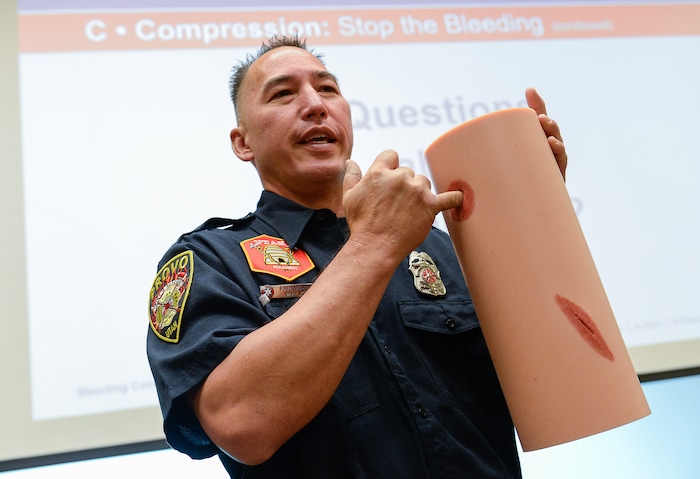

In Dewey’s class, participants learn to compress and pack wounds and use tourniquets.

But they also prepare mentally to take steps that may sound obvious but could be easy to neglect in a crisis — especially a violent crisis.

First, Dewey said, get safe and call 911 — and be ready to leave victims behind if the scene becomes unsafe.

“You can’t help anyone else if you’re not OK, so you don’t go into an unsafe scene,” Dewey said. “If there’s a car accident on the freeway and there’s still cars going, you don’t go running out there. ... If you’re in a shooting-type situation, don’t render aid until you’re absolutely sure you’re going to be safe to go help that person.”

Next, find the source of the bleeding, Dewey says. That likely will mean removing a victim’s clothes and searching for wounds. Jeans, for example, can soak up a lot of blood and make a person with a cut femoral artery look like they are bleeding less than they actually are.

“Make sure you get those off,” she said.

When helping at a scene with multiple victims, people providing assistance will need to make decisions about what treatment is best — and keep in mind who may need medical help first. Gunshot wounds through the abdomen, for example, may not bleed much externally, which likely means the patient is suffering from internal bleeding.

“There’s nothing we can do outside of a hospital to help these folks,” Dewey said. “When [medics] show up, we let them know, ‘These patients have internal injuries, so these patients need to go first.’”

Also make note of victims who are confused, unconscious or whose bleeding isn’t stopping even with aid, Dewey said; those patients will be priorities for medical care.

Once wounds are identified, they need pressure. Dewey and other teachers warned participants in a recent class of some unpleasant realities when treating a victim. Tourniquets are painful and frightening, and victims likely will fight whoever is applying it. Lock your elbows when compressing a wound; otherwise your arms will get tired while you wait for medics. Deep, large, gaping wounds may need to have cloth pushed into them, not just held on top of the cut — and if clean cloth isn’t available, use whatever is.

“Are we worried about putting a little dirt in the wound? We’re worried about saving a life immediately,” she said. “We might give them an infection, but all of these wounds are going to go to the OR when they go to the hospital. ... So shake the dirt off and use that, whatever you have.”

No matter how resistant a victim is, Dewey added, be kind.

“Be compassionate when you’re doing this,” she said. “They’re already hurting and in pain and upset by whatever situation they’re in. Be compassionate; tell them it’s going to hurt, but [you’re] saving their lives, and that as soon as [a medic] gets there he’ll give you some good drugs.”

Stop the Bleed classes have been going on in Utah for about a year, Robinson said. While they have recently been promoted in response to mass shootings, the skills apply to any traumatic injury that causes bleeding. Dixie Regional Medical Center in St. George, for example, advertised its class in connection with backcountry injuries common during summer’s outdoor recreation tourism.

“I thought it would be some good stuff to know in case anything did happen: any sort of accident that can cause major bleeding, whether a car accident, an accident in the home, in construction or anything — and hopefully it never happens, but if there’s another public shooting or public attack,” said Tim Tsai, 23, of Orem, who took Dewey’s class. ”

For class information, visit https://www.bleedingcontrol.org/.