Shante Johnson brushed a tear from her cheek.

“It just means a lot to always know that they keep their word when they said they’ll never be forgotten,” she said on Wednesday morning.

At the annual Utah Law Enforcement Memorial Service, people remember her and the sacrifice she and her family have made. They ask how her son — now 11 and getting taller than her — is doing. She has attended the memorial service every May since her husband, Draper police Sgt. Derek Johnson, was fatally shot in 2013.

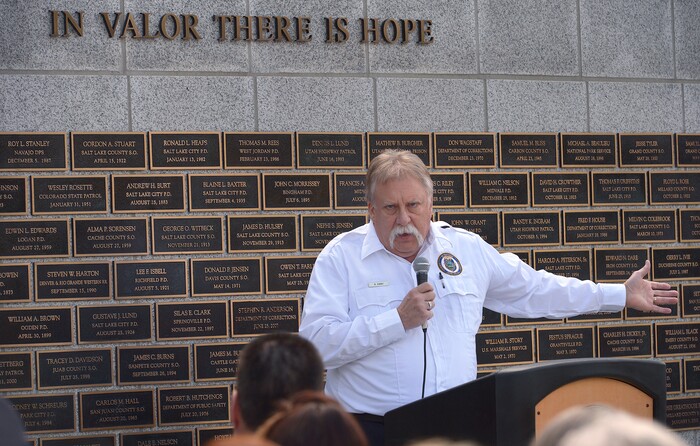

“The gatherings of this memorial aren’t to listen to speakers, but rather to gather in association with people who have lost so much and given so much. I’m speaking specifically about the family members in the audience and the men and women on this wall,” said Robert Kirby, the vice president and historian of the Utah Law Enforcement Memorial.

Near the end of Wednesday morning’s service, the notes of taps drifted over Shante Johnson and hundreds of others gathered in a concrete alcove on the west lawn of the state Capitol building where 142 plaques display the names of police officers who died in the line of duty.

“Our fallen are never forgotten,” Salt Lake County sheriff Rosie Rivera said.

Every once in a while, a year like 2017 comes along, with no officer fatalities. It’s not that often anymore, Kirby said. In 2015, no names were added to the memorial. In 2016, three names were added (two who died in 2016, and one whose death Kirby discovered in an old newspaper article).

“We are very much aware that this is an open-ended casualty list,” Kirby said. “And that the next to fall could very well be standing in this audience today. Please be careful. I don’t want to have to write about you.”

Though he is now a Salt Lake Tribune columnist, Kirby, a former police officer, researches and documents law enforcement officers who were killed in the line of duty.

He started 22 years ago, after finding that officers had been killed in the area he worked, yet he’d never heard about them.

“Why am I such a hostage to people I’ve never even met?” he wrote in a July 18, 1995, journal entry, which he read aloud on Wednesday.

There were times, while searching through stacks of information at the BYU Family History Library, that he felt the presence of those officers — a “line of people who still call me brother and need me to back them,” he wrote.

He had felt angry, he said. Enraged that officers were forgotten so easily. Since then, he has worked “with wonderful people in honoring our fallen officers,” he said.

Now, the names of the officers are displayed at the law enforcement memorial.

“We just appreciate the work they put into honoring them every year. It’s a special occasion and it means a lot to the families,” said Julie Leavitt, who was 11 years old when her father, Cache County Sheriff’s Lt. James R. Merrill died.

She, her mother and her brother come to the memorial every year, she said.

“I don’t believe we should just mourn their deaths but also give thanks that such people lived,” Kirby said. “They gave us what we have today.”

Bre Lasley built a relationship with police after Salt Lake City Officer Ben Hone saved her from a home invader in 2015.

She and her younger sister had been living in their new house near 800 South and 250 East for six days when a man forced his way into her bedroom window around midnight. In the basement of the house, he stabbed Lasley three times in the abdomen with a jagged hunting knife.

Lasley sent her sister, Kayli, out of the house. Hone, who’d been on his way to a different call, heard Kayli’s screams.

Hone went into the house, walked down 17 steps in the dark and found the intruder, holding a knife to Lasley’s throat. Hone gave the man three chances to drop the knife. When he didn’t, Hone fatally shot Lasley’s attacker in the face.

Earlier that day, Hone had learned that his wife was pregnant with their second child, Lasley said. He had thought about “his own daughters and his own family,” before going into the house, she added.

“The men and women behind the badge are heroes. It’s not just them that are sacrificing their lives,” she said, referring to officers’ families, her voice catching in her throat.

“Let no one wearing the badge be left alone. When the dreadful day comes and they lose a brother or sister, let them not walk alone,“ Rivera said. “Although our badges and patches are different, between each agency, they are a family crest. and in this family, no one walks alone.”