Powerful and problematic, the drama “Detroit” depicts with gritty realism a troubling time in recent American history, but raises more questions than it’s prepared to answer.

It’s 1967, and there’s chaos in the streets of American cities. African Americans are fed up with decaying inner-city living spaces and brutality from predominantly white police forces, and riots break out around the country. (A prologue, written by the scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. and illustrated by paintings by Jacob Laurence, details the historic forces leading up to this moment.) And nowhere were the riots so fierce, and the police crackdown more extreme, than in Detroit.

Director Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal, the team who explored the Iraq war in “The Hurt Locker” and chronicled the hunt for Osama Bin Laden in “Zero Dark Thirty,” don’t try to clear up the chaos at first. Instead, they make the viewer soak in it for a while, mixing archival footage with re-enactments to show how a police raid on an illegal nightclub agitated the neighbors, who threw rocks and bottles at the cops. Soon stores are being looted, buildings are being set afire, and Gov. George Romney (yup, Mitt’s dad) is calling out the National Guard to restore order.

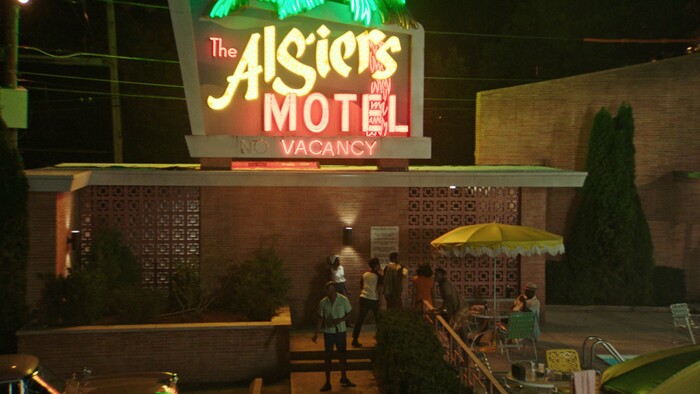

The event on which Bigelow and Boal focus their attention happens on the third night of rioting, July 25, 1967, at the Algiers Motel. Locals knew the Algiers and the three-story house behind it that was the motel’s annex as a party spot, but the Detroit cops targeted it for drugs and prostitution raids. During the riots, it was also a place to hide until morning, when the curfew was lifted.

Boal’s script brings in some of the people whose lives will collide at the Algiers gradually, from different walks of life. There’s Larry “Cleveland” Reed (Algee Smith), lead singer for a Motown-in-waiting singing group, who ends up at the Algiers with his friend and band manager, Fred Temple (Jacob Latimore). There’s Robert Greene (Anthony Mackie), an honorably discharged Airborne soldier just back from Vietnam. And there are two white teens from Ohio, Juli Hysell (Hannah Murray) and Karen Malloy (Kaitlyn Never).

On the side of the law, the movie introduces Melvin Dismukes (John Boyega), a security guard at a nearby shop. We also meet a Detroit cop, Krauss (Will Poulter), who is already on a homicide detective’s radar for shooting a looter in the back, and his partners, Demens (Jack Reynor) and Flynn (Ben O’Toole). It’s important to note that Dismukes is black and the cops are white.

When one of the Algiers partygoers (Jason Mitchell) fires a starter pistol, cops and National Guardsmen posted a block away panic and think they’re under fire from a sniper. The three Detroit cops lead a raid in the Algiers’ annex, with help from Guardsmen and even Dismukes, who sees himself as a liaison between the white cops and the black motel denizens. But the sight of two white teens in the company of several black men sends the officers into a rage.

What follows in Bigelow and Boal’s detailed and tensely realized dramatization — which, they acknowledge, is based on incomplete information — is a harrowing night of thuggish cops terrorizing innocent civilians, with some of those civilians ending up dead.

The movie provides pseudonyms to the three Detroit cops, but not to Dismukes or the people the police threatened, bullied, beat up and shot. That choice may have been necessary, presumably for legal reasons, but it feels like another injustice — revictimizing the people in the Algiers, while allowing the bad cops to get away with murder once again.

The movie concludes with a trial, and anyone who pays attention to recent accounts of police officers accused of killing young black men knows how this all will end.

Therein lies the central problem with “Detroit”: For all of Boal’s skill in condensing information and Bigelow’s talent at creating riveting images and drum-tight tension, they are applying it to an event that provokes anger and cynicism without offering a way to channel it.

“Detroit” asks audiences to learn from America’s blood-stained history. What it teaches us is that the list of victims of police violence — that includes Eric Garner in Staten Island, Michael Brown in Ferguson, Freddie Gray in Baltimore — is longer and sadder than most Americans choose to remember.

* * *<br>’Detroit’<br>Police brutalize African-American motel occupants during the urban riots of 1967 in this tense but troubling dramatization.<br>Where • Theaters everywhere<br>When • Opens Friday, Aug. 4<br>Rating • R for strong violence and pervasive language.<br>Running time • 143 minutes.