This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2017, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Ten rows deep they packed Main Street — thousands of men and women crammed in to catch flashes of Utah's conquering heroes.

At the time, Lyman Clark heard someone remark it was the most significant procession in the valley since Brigham Young arrived. The then-teenager from Clearfield had little reason to doubt it.

"It was a big deal — people from all over the state came," he said. "I have no idea how many thousands of people were there."

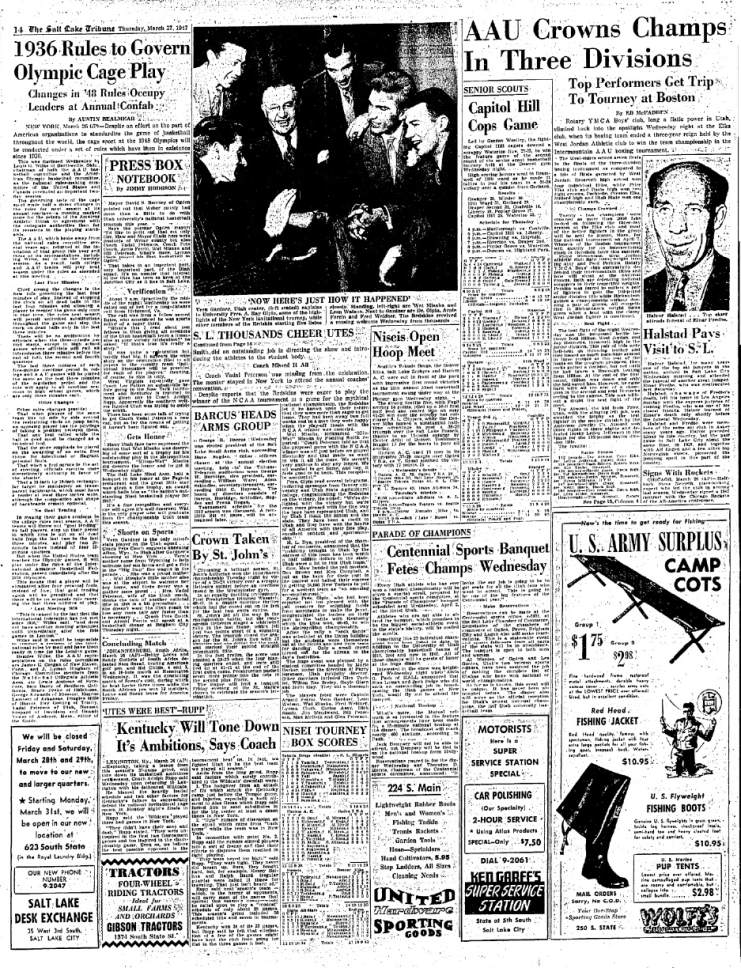

The parade on March 26, 1947, drew an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 souls, according to a Tribune account. They gathered to celebrate Utah basketball's triumph in the National Invitational Tournament, described then as "the most tumultuous welcome in the history of athletics in this state."

That idea is quaint now: Now, the NIT is second fiddle to the NCAA Tournament's March Madness. When the modern-day Utes lost in the first-round of the NIT to Boise State on Tuesday, just over 4,000 fans attended — about a third of Utah's average attendance. Last year's NIT title game between George Washington and Valparaiso drew just over 7,000 fans.

In 1947, it was 18,467 who filled Madison Square Garden, which was about 15 blocks north of MSG's current location. The hardcourt contained dead planks and the cigar smoke was so thick, former All-American Arnie Ferrin recalled, that when the team stood for the national anthem, they couldn't see the flag at the top of the arena.

The 70th anniversary of Utah's feat — the team was the underdog in each of its three wins over Duquesne, West Virginia and Kentucky — finds only a few members of the team remaining. But those who remain, including Ferrin, Clark and tournament hero Wat Misaka, treasure what memories they have from when winning the NIT was viewed as arguably the biggest athletic achievement in the state up to that time, including Utah's 1944 NCAA championship.

As sports scribe Jimmy Hodgson penned in The Tribune in 1947: "Never before has a sports event created such a stir and so much commotion as the accomplishments of this Centennial Utah basketball squad."

—

The team, the dream

As most championship teams do, the 1947 Blitz Kids had experience. Ferrin, Misaka and Dick Smuin were all returners from Utah's charmed NCAA run in Kansas City, as well as a Red Cross Benefit win over St. John's in New York in 1944.

Something else all the Utes had: Military experience. Almost to a man, they were in "the service," with Ferrin in the Army and Clark in the Air Force. That helped coach Vadal Peterson instill the quality that he believed would be his chief advantage on the court: physical conditioning.

"His mindset was if you're in great condition and you can defend, you'll have a chance," Ferrin recalled. "We were in really good condition."

It was critical because Utah played mostly without substitutes. Ferrin was Utah's best and most versatile scorer, his arsenal featuring a "scoop shot" that has escaped the modern game. At 5-foot-7, Misaka was a stalwart and antagonistic defender. The star newcomer that season was Vern Gardner, a 6-foot-5 Wyoming boy who played rugged and tough both inside and out. Sometimes the Utes subbed once per game. Other times they didn't sub at all.

While most of Utah's players had never been to New York, several of them had in the prior tournaments — and they had left an impression. When the basketball team arrived a few days prior to the NIT, they routinely were recognized on the street.

"For some reason they took a liking to us," Clark said. "Arnie and Vern had their pictures in the paper every other day. They recognized Arnie more than everybody else."

In both Ferrin's and Clark's estimation, on most nights, Kentucky would've been the better team. They featured the great Ralph Beard, who was once called the best guard in the game by Bob Cousy. The Wildcats were coached by Adolph Rupp, who would go on to win four NCAA titles.

But Utah had another advantage: By the time they faced off against Kentucky on March 24, they were the darlings of the city fans, whom they had won over with their grit in 1944. A Tribune account also describes two "yell leaders," Don Brown and Ken Campbell, who trekked to New York for the NIT and taught Ute-backing chants to the crowd, including "U-T-A-H."

When they won, the Tribune story called the audience applause "one of the greatest ovations in Garden history."

"It almost felt like we had the homecourt advantage," Ferrin said. "There were more people cheering for us than Kentucky."

Utah won in dramatic fashion, edging the Wildcats 49-45. Misaka smothered Beard, who was held to one point on a free throw. Clark described Misaka's style as "a synchronized dance — wherever he went, Wat was there."

Misaka was a particular crowd favorite, and it was noticed by the New York Knicks, who signed him later that year. He only played three games, but Misaka still stands as the first person of color to play professional basketball.

—

Citywide party

The championship was won. The Utes stormed the floor after the buzzer, took the Kelleher Trophy and hoisted Peterson on their shoulders.

But they had little idea the party Salt Lake City was about to throw for them.

"I think that they said while we were in a plane, there was going to be a big crowd there to greet us," Clark said. "That was the first time any of us knew."

At the airport were 5,000 people who had driven to the edge of the Great Salt Lake to meet the United Air Lines flight carrying the "Cinderella Cagers." They rode into town in cars wearing red and white, each player getting his own convertible donning his name. Peterson was the only key member missing, having stayed in New York for an annual coaching convention.

The only one who didn't ride in a convertible was Gardner, the tournament's most outstanding player who sat astride a fire engine called "Big Dan."

They first went down Main Street, which had been shut down and filled with throngs of fans. The city had hung centennial banners from the buildings extra early for the team's return.

They stopped for 15 minutes in front of the city commerce building, where the governor and the mayors of both Salt Lake City and Ogden made remarks for the crowd. Gardner was presented with a trophy for his play in the tournament — as well as a kiss from Days of '47 queen Calleen Robinson ("a regular movie kiss, too" the Tribune account read).

The celebration continued at Kingsbury Hall, where the university president joined a rally of students who were abuzz to see the conquering team. The players spoke, filling in the gaps for those who had listened to the radio broadcast at home. Officials read off telegrams of congratulations that had been sent from around the country. The team later attended a dinner at Hotel Utah, which had been scheduled the following month to celebrate the state centennial, but was moved up to accommodate them.

For at least a month afterward, Ferrin recalled, the team or individual players were asked to speak at assemblies and dinners: Lion's Club, Rotary Club — you name it.

"I think it was just an occasion to celebrate a big thing in the community," he said. "It seemed like the whole state had been listening in. We had a lot of people in the foxhole with us."

—

Lasting memories

When writing "Utah Basketball: A History of the Runnin' Utes Since 1908," author Jason Hansen had a dilemma: In his ranking of Utah's greatest games, how did he order the NCAA and NIT championships?

It was Bill Marcroft, the voice of the Utes for 35 years, who convinced him to push the NCAA title to No. 1, given the mountainous adversity the 1944 team faced to win it all. The NIT remains No. 2, and the wins over Duquesne (17) and West Virginia (8) still hold a hallowed place in Hansen's view of school history.

"In 1947, the NIT was the biggest deal," he said. "They were considered the best."

The 70 years since Salt Lake City shut down Main Street has seen the value of the NIT change: As the NCAA Tournament became televised in the 1950s, it gained importance, and going to the Garden wasn't as big of an event. Today, being the NIT champion is a bittersweet honor for the best team to miss the NCAA Tournament.

It's also watered down a bit for Ferrin, who said his experience as chairman of the tournament committee as Utah's athletic director gave him an added an appreciation for his own NCAA title success. But the 1947 team does hold a place in his heart and among the walls of his office, where he keeps certificates and pictures from his All-American season — the ones that survived a house fire he had decades ago.

For Clark, the NIT game is his claim to fame in his basketball career. He jokes with Ferrin that he wouldn't have scored as many points without Clark's own stellar passing. As the years go on, he said, it seems that he gains esteem as well.

"When people introduce me, they say, 'He was an All-American,' — I used to deny it vehemently, but now I just say 'sure,'" Clark joked. "It was a big deal for the whole state to get behind and take a little bit of credit. It was really a pleasant experience."

Twitter: @kylegoon —

About the 1947 team

• Went 19-5, 10-2 to finish second in the Skyline Conference.

• Beat Duquesne (45-44), West Virginia (64-62) and Kentucky (49-45 to win the championship).

• Center Vern Gardner was tournament MVP.

• Between 1916 AAU championship, 1944 NCAA championship and 1947 NIT championship, Utah is the only program to win all three national titles.