This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

LaVell Edwards said he loved flowers. And he loved when he drove home from work everyday to eat lunch with his wife, Patti, for some three decades, the way the shades and seasons changed the colors of Rock Canyon, the massive cliff outside his front yard.

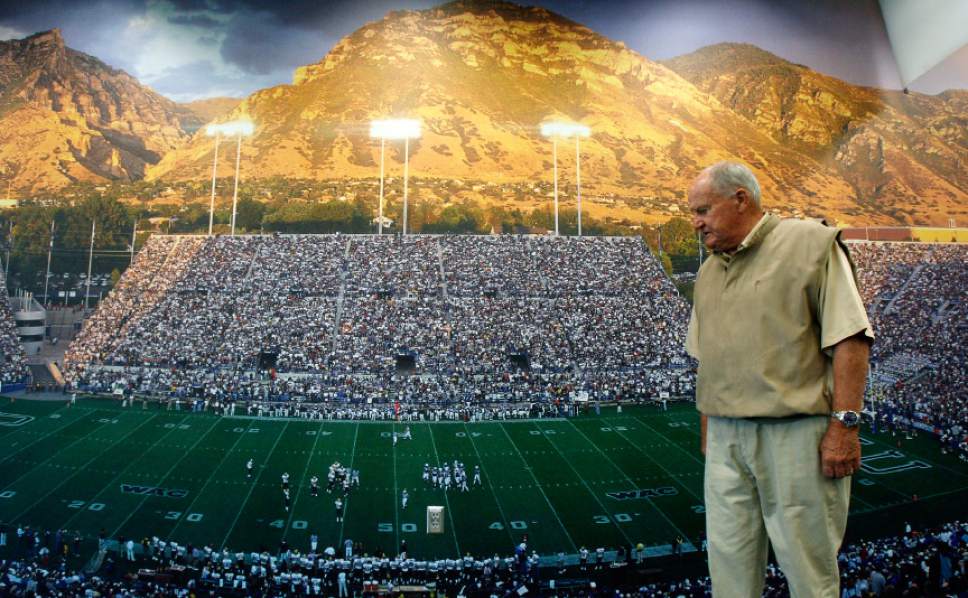

So it is that one of the best college football coaches in history, a man respected and revered enough to have a stadium named after him while he was still alive, loved dahlias and chrysanthemums, snapdragons and daylilies, daisies and zinnias and philodendrons, planted and tended by him in bunches around his house, and the scenic changes on a canyon wall that only those who paused to look can see.

"I just looked up there and thought, 'Holy Cow! What a sight,'" he once told me. He stopped for a moment and then added: "I've noticed that it's especially that way when the leaves turn in the fall."

The expression on his face, the tone of his voice, so full of appreciation for nature's splendor — I'll never forget. That it came a few days before BYU's season opener that year made it even more memorable.

How many college football coaches have you heard of who would take the time to soak in visuals like that, soak in life, in the manner Edwards did? The man had an ear for great music, a taste for great books — his favorite of all time was "Lonesome Dove" — and eyes in which the tide would unabashedly rise when he saw a sad movie. His view of the game of golf was darn-near religious, but still not as spiritual to him as kneeling down to supplicate the Almighty in prayer. He made room for all of those things and more.

Most head coaches have to be reminded to break from film study and team meetings long enough to breathe.

Not LaVell Edwards.

He breathed in everything. The game's narrow parameters were nowhere near vast enough for him: "Football has been important to me," he said that day, "but it's never been the most important thing."

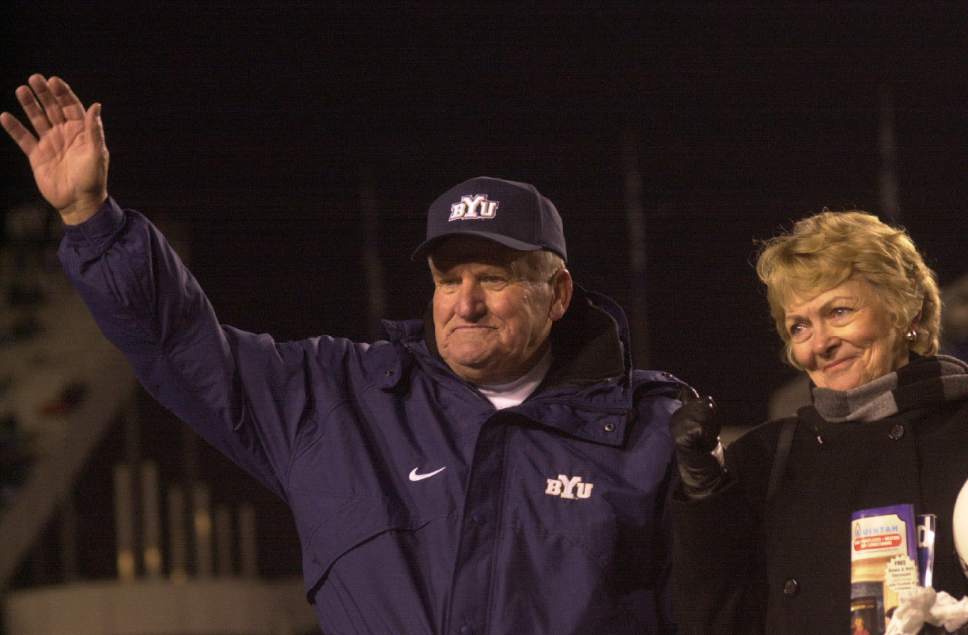

When he died this week, at the age of 86, there was little to mourn, then, other than the pain of saying goodbye, and a lot to celebrate, an existence richer and fuller than LaVell himself could have imagined.

The winning wasn't bad, either.

In his later years as a coach, I asked Edwards if BYU had a mandatory retirement age, and he answered: "Not if you're winning."

He won.

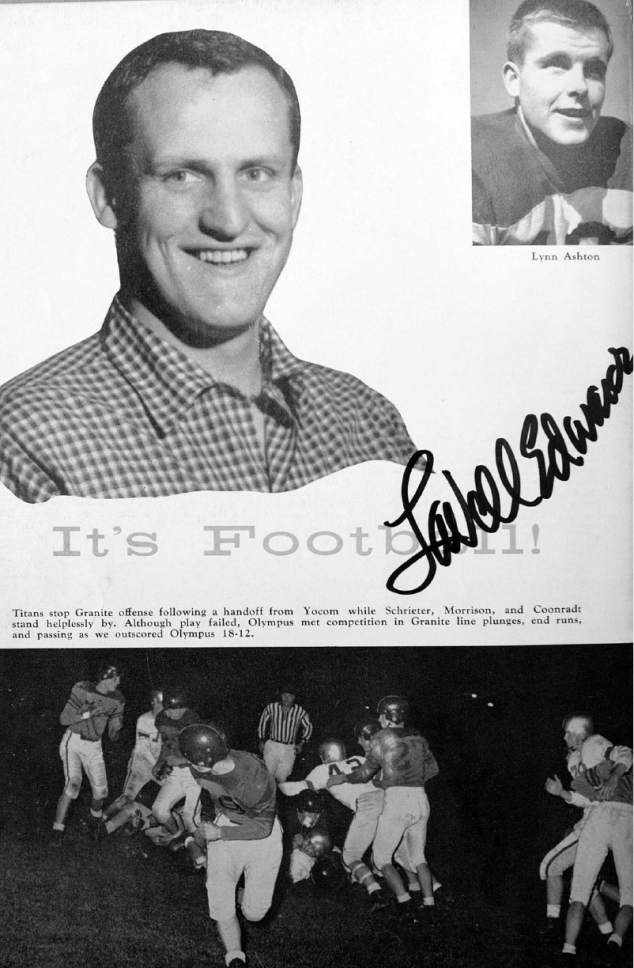

Before Edwards took the wheel at BYU in 1972, the school's all-time record in football was 173-232-23. His record: 257-101-3. He changed the way people saw football at BYU, and the way outsiders saw BYU because of football. When he announced his coming retirement at the start of the 2000 season, effective at season's end, he said, "We made football a presence at BYU. I'm as satisfied with that as anything."

Out of desperation, and inspired by the success achieved by Jim Plunkett at Stanford back in the day, he transformed BYU into a passer's dream. And the passers came, all right — Gary Sheide, Gifford Nielsen, Marc Wilson, Jim McMahon, Steve Young, Robbie Bosco, Ty Detmer, Steve Sarkisian, and the rest, and so did a national championship, 20 league titles, 22 bowl games, a Heisman winner, a couple of Outland winners, and a victory in the Cotton Bowl.

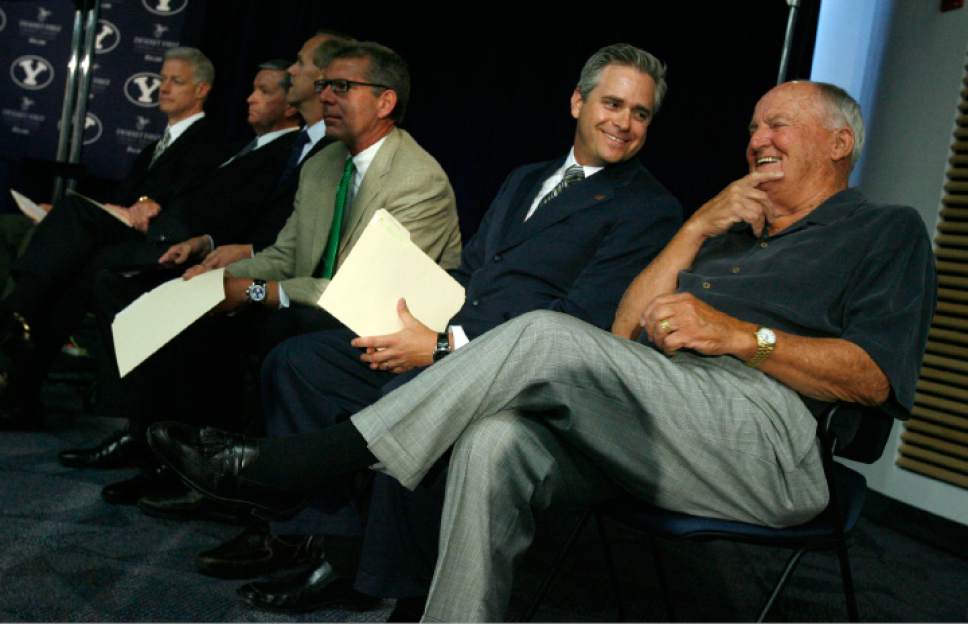

The outrageous success didn't affect or change Edwards. It made him more of what he already was — as comfortable a man in his own corporal state as God ever created. His personality was that of an overstuffed Barc-O-Lounger, his personage on the sidelines that of a slab of granite. Still, he had a razor-sharp wit that would emerge out from between the sofa cushions.

For instance, when Young was a neophyte starter for him, playing at Georgia, the quarterback threw an interception. Edwards told him not to worry about it. Young said he wouldn't. When the quarterback threw another pick, Edwards said, "Don't worry about it." Young said he wouldn't. When he threw a third pick, the coach remained patient, essentially telling his quarterback, "No big deal." When Young threw a fourth interception, Edwards asked his QB if he was worried about it. Young said, "Nah." Edwards asked, in so many words, "Isn't about time you start worrying about it?"

Edwards cared deeply about his kids — one a writer, one a lawyer, one a doctor. His children's children, and their children, loved him. And he loved them back.

Everybody loved LaVell.

That's what should be written on his tombstone. Not his win-loss record. Not what other coaches, cursed with such narrow focus, obsessed over. What he always knew was the most important thing. And maybe somebody will plant a few daisies and dahlias and daylilies nearby, and take the time to more fully appreciate the way the leaves turn in the fall. He would like that.

GORDON MONSON hosts "The Big Show" with Spence Checketts weekdays from 3-7 p.m. on the Zone Sports Network, 97.5 FM and 1280 AM. Twitter: @GordonMonson.