This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

This is not a Jerry Sloan eulogy.

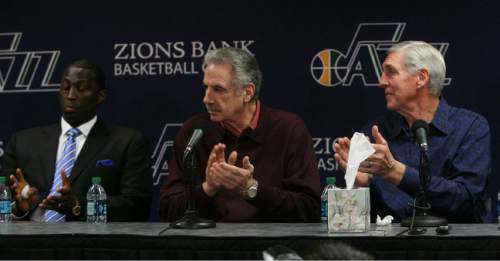

Five years ago, I wrote about the funereal aura of his farewell news conference as the Jazz's coach, as people talked about him in the past tense and we all realized that Utah would never be quite the same, because a Midwesterner who had become so much of the heart of our state was stepping away from his job.

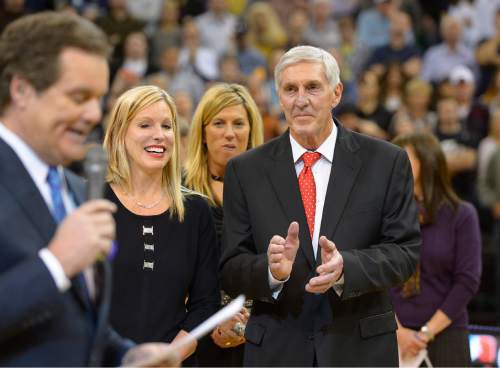

This is different. He's still with us, still one of us, watching the Jazz play from Section 8, Row 11 in Vivint Smart Home Arena, adjacent to the media platform above the tunnel where the home team enters and exits. Part of my routine is to glance over and see if Jerry and his wife, Tammy, are in their seats — as almost always is the case.

Yet in observing Sloan as he watches games, seeing how he interacts with people around him, I've wondered about him lately. So have many others. And that's why he's publicly sharing how Parkinson's disease and another neurological disorder have affected him at age 74.

This news hits home. My brother was diagnosed with Parkinson's at 46, knocking his college football coaching career off course. The accompanying tremors are a reminder that treatments exist, but not cures.

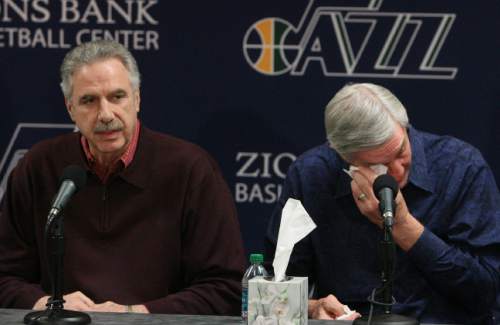

That's not a plea for empathy, nor is Jerry's disclosure. I believe this is just his way of dealing with a health issue, getting it out there and facing it daily. That's exactly how he handled the cancer diagnosis of his first wife, Bobbye, in January 2004, as the couple appeared at a news conference to make the announcement and asked for support in a one-time setting. She died five months later.

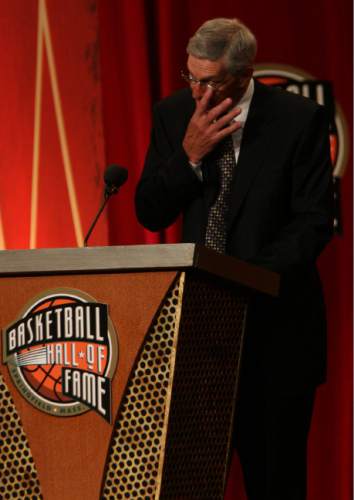

Through that experience, Jerry showed his human side. That was refreshing. His wife was the tougher one; the hardened Midwestern farmer was the one who cried. And that episode was all the more reason for Utahns to become attached to him. We all shared in the trials of Bobbye's illness and Jerry's emotional loss, and nodded approvingly as he married a Utahn two years later.

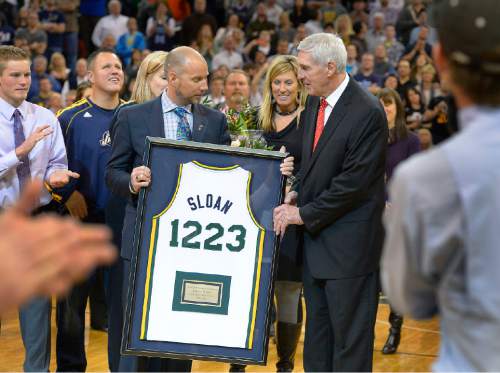

And then we mourned in a different way in 2011 when he suddenly resigned as the Jazz's coach. This guy is part of the fabric of life here. We may have worried that we were losing him to the southern Illinois farm when he retired, but Tammy's influence has kept him in the Salt Lake Valley, to our benefit.

He's one of us, permanently. As outgoing Jazz president Randy Rigby once said, "His style resonates very well with all of us from Utah. He was so sincere and genuine. That's what people loved about him. They could relate to Jerry Sloan."

See what I mean? Rigby's words were wonderful, but the tense was wrong. Everything he said about Jerry five years ago applies today, only with these words substituted: "is," "love" and "can."

If anything, Jerry is more relatable than ever. We all wish Sloan would be as indestructible as his image suggests, but there's something about the way he accepts his human frailty and moves forward that makes him even more lovable.

The most memorable series of interviews I've ever done came during the Jazz's last playoff run of the Sloan era, when I delved into the stories of fans who were so attached to the team that families were compelled to mention their devotion to the Jazz in their obituaries. In nearly every case, the relatives I contacted would trace those ties to admiration for Sloan.

This is not one of those obits. Jerry presumably, hopefully, will remain with us in Utah for a long time. He may not always be the exact same guy we've known for more than three decades, but who among us could make such a claim, anyway?

Jerry's evolving, just like all of us, and we'll be here for him. As the late Bobbye Sloan said, "It's too bad that we have to get sick to find out how much people care about you."

The love and concern shown to Jerry Sloan surely will resemble that outpouring. We're Utahns. That's what we do.

Twitter: @tribkurt