This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2016, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Some Utah high school basketball coaches, including three of the six black coaches who run boys' programs in the state, are concerned about the officiating at their teams' games — specifically how referees are interacting with minority coaches and athletes, and how at least some officials appear to condone racially charged comments directed toward their players.

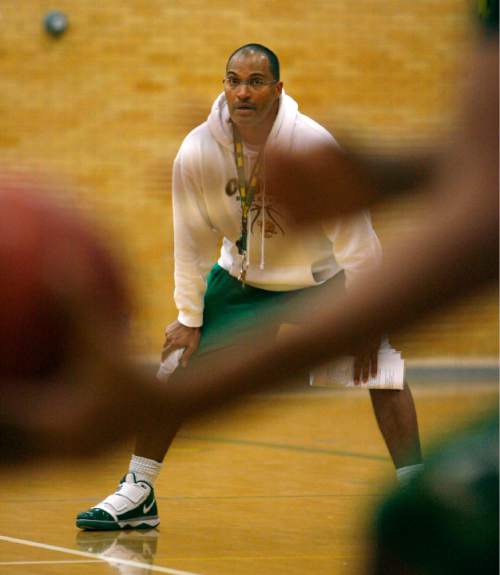

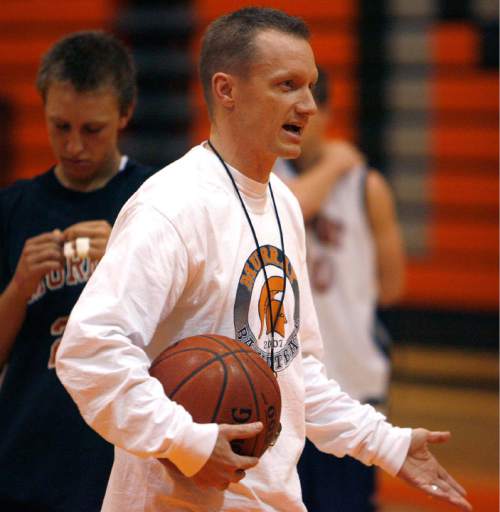

Layton Christian's Bobby Porter, Kearns' Dan Cosby, Summit Academy's Evric Gray and Murray's Jason Workman — who is white but has two black assistant coaches and a multicultural roster — met this week with staff from the Utah High School Activities Association (UHSAA) and two members of the joint board of officials.

The coaches say they are reluctant to accuse game officials of racial bias, but enough incidents have occurred during the first month of the season that they felt compelled to raise the issue.

"Is it a coincidence? We don't know. We're trying to figure it out," Gray said. The UHSAA "is trying to get it right. They're really good people. Am I calling [game officials] racist? No, I'm not, but the communication sucks."

One issue raised during the Tuesday meeting was the casual use of racial slurs by players and spectators during games, particularly in rural towns. Gray says he has expressed his concern to game officials about the potential hazards of such taunting, with tempers flaring and things potentially getting out of control. But the Summit Academy coach maintains referees have routinely dismissed his fears and ignored him.

"We have issues where kids are called the 'N-word,' and when I try and explain it [to the officials, the response is], 'Just coach your team. Don't worry about it,' " Gray said. "I'm like, 'OK. Our kids are getting a little frustrated.' Nothing ever happens."

Under UHSAA rules, officials can eject players for inappropriate behavior; fans also can be booted out, in liaison with an on-site school administrator.

Another topic raised by the coaches was how game officials handle the late stages of lopsided games, when the trailing team's players get increasingly frustrated and their play tends to get more physical. Their own teams, they said, don't seem to get the benefit of the doubt.

"It starts getting more chippy, and then the officials come over to us — us being the teams with African-American players — and say, 'You got to control your kids,' Workman said. "We're up 20 [and the other team is] frustrated and fouling. Why aren't [the officials] over there? It's the assumption it's got to be us; it's got to be our 'thugs.' It sends the wrong message."

Kearns forward Kur Kuath said he frequently is not afforded the same opportunities to discuss calls with officials as his white teammates.

"Things happen and the refs won't even let me talk to them about it. The refs would say some rude things," said Kuath, who claims he was told to "stop [expletive] whining" on more than one occasion.

"It's just like, I'm trying to talk to you guys and tell you what's wrong. … It doesn't feel right," he said.

The coaches presented no data at the meeting to quantify what they say they're experiencing on the court. But Cosby, whose team was on the short end of a 28-9 foul disparity in a two-point loss to Dixie earlier this season, urged UHSAA officials to take their concerns seriously.

"Find the cause," he said, "and the problem will cease."

Layton Christian's Porter said he came away from the meeting encouraged.

"The thing that came out [Tuesday] that I thought was really good, is, people forget officials are human, too," Porter said. "There is no perfection on either side. That's really important."

Jeff Cluff, UHSAA's assistant director and director of officiating, says several factors could be at work, ranging from an official's stress level or temperament to possible physical exhaustion or a simple lack of awareness. All might lead to officiating mistakes on a subconscious level, he said.

Cluff says that communication between officials and coaches is the most complicated issue he deals with daily. He adds that UHSAA has "zero tolerance" for discrimination and "if there is an issue regarding race, we need to know about those specific incidences and handle it."

Porter, who organized the meeting, emphasized that he is not alleging premeditated prejudice on the part of referees, but says a little awareness and empathy go a long way.

"It would be stupid of me to say racism doesn't exist throughout the country, but I see things getting better," said Porter, who has coached in Utah for 16 years. "I think people get better when they become more familiar and understand how people perceive things. When you do training and things of that nature, people eventually come around."

The four chapters of the state's officials association are expected to discuss the coaches' concerns during their regularly scheduled meeting Jan. 25 — "if not sooner," according to Cluff.

"We have a lot of games between now and then," he said, "and the sooner we can address these issues and start to create awareness, the better off we are."

Cluff described the Tuesday meeting as "very amenable" and "constructive," adding, "I felt like we're going in the right direction, not only regarding officiating, but sportsmanship as a whole in the state of Utah."

Porter agreed. "Talking does a lot of good," he said. "It's a situation we have to continue to work to make it better — to not ignore the elephant in the room — and to get these things resolved."

Twitter: @trevorphibbs