This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2015, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

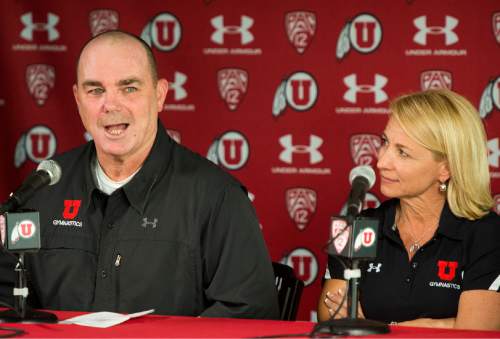

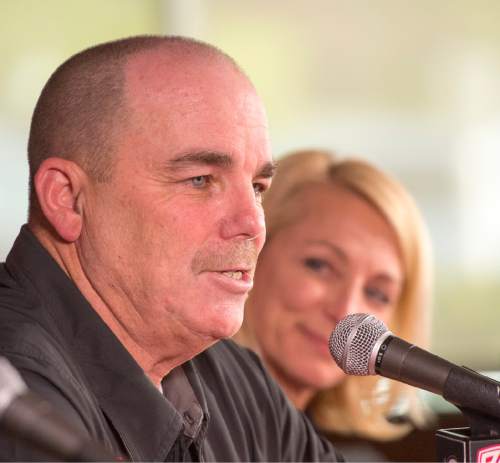

Greg Marsden sat in front of a microphone on Tuesday, thanked you and you and you and you and you, thanked his athletes, his school, his fans, his wife, his boss and his boosters, and said what everybody already knew, as of Monday.

He is letting go. Letting go of a gymnastics empire he built and sustained over the span of four decades, straight from the time when he wouldn't have recognized a straddle Jaeger from a Shaposhnikova release to his days of complete expertise now. What he did recognize back then was that he had no money. As a graduate sports psychology student who volunteered in 1975-76 to help establish Utah's program for the yearly financial bonanza of $1,500, he studied and he learned.

And, man, he won.

Ten national championships and, just as significantly, annual contention for that top spot, including this season's second-place finish. In Marsden's 40 years as head coach, his teams qualified to compete at every single NCAA Championship ever held, all 34 of them. His overall career meet record: 1,048-208-8. He is the most successful coach in the history of college women's gymnastics.

Remarkable, considering Marsden at the start had never coached the sport and from a technical standpoint knew about the same as you or I do, maybe a little more. It took him all of five years to win that first national title. He read books, recruited, worked all aspects of program building and marketing, transforming women's gymnastics in this state from a sideshow into a marquee event that regularly fills the Huntsman Center. This past season, the Utes drew an average of 15,000 fans

That's sort of a ridiculous number, but one in line with the Utes' run-up since 1990, a span during which they've averaged over 11,000 spectators.

The root and rudiments of that success bubbled up from Marsden himself.

While he lacked the clinical, classical background of, say, Bela Karolyi, he was familiar with the far reaches of resolve and tenacity, of mental and emotional toughness. I'll never forget the first time I interviewed Marsden, some 20 years ago. I'd sat in front of driven, competitive people a thousand times before, but he was an amplified version of most, a coaching rendition of a Plott Hound on a Porterhouse. He was determined and relentless. He filled me in, telling about his familial frame of reference and what it took to make his way through it.

His father, a Navy weather pilot, was killed when Marsden was 3 years old. He flew into a typhoon over the Pacific Ocean and never flew out. His mother suffered from mental illness and, at times, was institutionalized. His grandmother reared him and loved him, and then died when Marsden was a teenager. His grandfather taught him discipline and argued with him — a lot — before he committed suicide.

The primary lesson taken from all of that was this: How to fight and how to survive and how to win.

That's what the coach, both as a neophyte and as a veteran, brought to his teams. Anybody who has spent time around top-level gymnasts knows they already are tough. They may be petite, they may be elegant in their form and in their movements, but on the sliding scale of athletic grit and resiliency, they are more Gunnery Sergeant Hartman than they are Sweet Polly Purebread.

Marsden poured diesel fuel on that fire.

"I learned never to feel sorry for myself," he said back then. "I learned to be independent, to be responsible for my decisions, my actions. I learned not to make excuses."

He certainly didn't want to hear that last thing from his athletes.

"My life has been a series of triumphs and tragedies and struggles I have grown from," he said. "As I look back, I've learned more from my mistakes than from the highlights, the national championships."

His biggest gaffe, he said at that time, was falling in love many years ago with a 19-year-old freshman — Megan McCunniff — and later marrying her: "The best mistake I ever made. Megan and I are absolutely happy. But it was the wrong thing to do."

After years of coaching together, winning together, Megan Marsden will take over the program in the lead role starting now, along with Tom Farden.

They can have it, Marsden said on Tuesday. The former king won't be meddling with his old kingdom. He doesn't know exactly what he will be doing because, as he said it, "I have no hobbies."

So, the man who built the program, who accomplished everything there is to accomplish in the college version of his sport, whose trophy case and whose life with wife and family is pretty much full and fully fulfilling, having hauled his sport from almost nothing to something substantial, is letting go.

"I'm a very lucky man that I got to do a job for 40 years that was my passion, that I couldn't wait to get out of bed to get to," he said. "That's all any man could ask for. It's been great."

GORDON MONSON hosts "The Big Show" with Spence Checketts weekdays from 3-7 p.m. on 97.5 FM and 1280 AM The Zone. Twitter: @GordonMonson.