This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

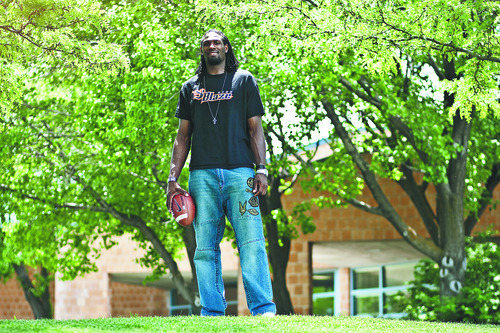

When he walks off the gridiron after morning practice, Caesar Rayford prepares himself for his next battle of the day. It's not a job that requires him to be physically menacing — as he must be as a defensive end for the Utah Blaze — but he still has to be strong.

Rayford works as a part-time counselor at Decker Lake Youth Center, a detention facility for troubled youngsters in West Valley City. The 25-year-old football player spends hours every week helping kids with their work, playing games with them or simply talking.

"A lot of these kids don't have a person in their life who they can talk to about stuff," Rayford says. "When I was a kid, I could've gone either way, but I had people who influenced me. That can change your life."

Rayford is one of a handful of Blaze players who work part time during the season. It's akin to being split between worlds: On one hand, many of the younger players such as Rayford hope to move up to the NFL one day. But it's not stopping players from investing in a future beyond football.

Rayford has been interested in social work for a while. He left a lucrative job as a car salesman three months ago to have a chance to work at Decker Lake.

As an athlete, Rayford realizes many of the youths there look up to him and listen to the advice he offers. Beyond his playing days, he sees a future as a caseworker or another job where he can see the effect of his influence as a role model.

"Football gives you opportunities that you can take advantage of, but it's only temporary," he says. "In my eyes, I'll take making positive, real change over being filthy rich."

Not that Arena Football League players are rich — playing football full time is a long way off for men who make about $400 per week. Part-time jobs during the season open doors to make some extra money and gain work experience.

Defensive back LaBrose Hedgemon works for PMI Coaching, a consulting firm based in Lehi. After morning practices, he commutes using the car his boss lends him and works anywhere from six to eight hours a day.

At 26, Hedgemon still has ambitions to rise to the NFL. But practicality demands that he seek out other options, and PMI is a good job — definitely better than when he was stocking pet food for a living.

"It takes a lot of time-management to stay on top of it," Hedgemon says. "You can survive on our salary, but for the things you want, you have to work for them. Just in case something happens, I have a backup now, which is the reason I got a job."

It's a tricky balance, but players know not being ready for the future is a dangerous trap. Life after football will come, and when it does, guys such as Rayford will be prepared.

"It can be draining, at times, when you get out of a hard practice and then the kids act out," he says.

"But it's cool to see how your actions make a difference. It lets you know if something happens to you in football, you're not stuck."

Twitter: @kylegoon —

Other players'other gigs

Not everyone works during the season — these guys take on a new persona when football is over:

Ben Stallings, fullback • Officer at Boliver County Regional Correctional Facility

Chris Bocage, receiver • Football coach at Lewisberg College (N.C.)

Brandon Taylor, defensive back • Permanent substitute/teacher's aide and coach at Robbinsville High School (N.J.)/personal trainer at Sweat Institute —

Pittsburgh Power at Utah Blaze

P At EnergySolutions Arena

Saturday, 7 p.m.