This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In pushing his "Healthy Utah" private-insurance alternative to expanding Medicaid, Gov. Gary Herbert must overcome Republican angst over "Obamacare" and ideological distaste for entitlement programs.

Political insiders put better odds on his brokering a funding deal with the feds than winning over members of his own party in Utah's Republican-led Legislature.

But states have faced this decision twice before: once with the creation of Medicaid in 1965 and again, decades later, with the Children's Health Insurance Program, or CHIP.

And while there was furor over both programs, the lure of federal cash proved too great for even the most obstinate of states.

—

'Too far, too fast' • Congress authorizes millions in federal funds to provide health care to the poor and a year later, only half the states have accepted the money.

The year is 1966 — not 2014, though the description applies to the current debate over the Affordable Care Act's multibillion-dollar expansion of Medicaid.

Medicaid and its cousin, Medicare for the elderly, passed Congress as an amendment to the Social Security Act and were signed into law July 30, 1965, by President Lyndon Johnson.

Utah was one of the first 20 states to sign up. Cal Rampton, a Democrat, was governor.

"I remember that my father jumped on it pretty quickly because it was kind of the brainchild of his buddy Lyndon Johnson," recalls the late governor's son, Vince Rampton, a lawyer in Salt Lake City.

But just as Utah's plan was approved in July 1966, alarms sounded nationally about Medicaid's costs.

"Congress may decide to pull the brake on the federal financing of health care," The Associated Press reported in the July 9, 1966, edition of The Salt Lake Tribune. "... The House Ways and Means Committee has held two closed-door hearings to explore whether Congress unwittingly went too far too fast last year in inviting the states to dip into the treasury for medical aid funds."

—

A state prerogative • Unlike Medicare, Medicaid is run and partially funded by states.

The difference "had a lot to do with the politics of poverty," said Alan Weil, executive director of the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Conservative, mostly Southern, states blocked national aid programs they felt were too generous, believing they would eliminate Americans' motivation to work, said Weil.

So offering Medicaid is voluntary and states have some discretion in setting eligibility rules, which are a near constant source of political wrangling.

States were enticed to adopt the program, however, by a promise that the federal government would pay 50 percent to 83 percent of the costs, depending on a state's per capita income.

By 1970, a final group of eight, mostly Southern, states joined Medicaid's early adopters. Arizona was the last, signing up in 1982.

Funding also quickly became a problem for states. One month into Utah's program, on Aug. 13, 1966, The Tribune reported the state's price tag was expected to more than double in 1967 to $12 million.

Then spending rose an annual average of 22 percent from 1973 to 1984 — a reflection of America's spiraling health care costs. In 1984, the state's share was $130 million, according to data from the Utah Hospital Association.

—

Expanding for children • Today Medicaid covers about 279,000 Utahns and costs $2.2 billion, two-thirds of which comes from Uncle Sam.

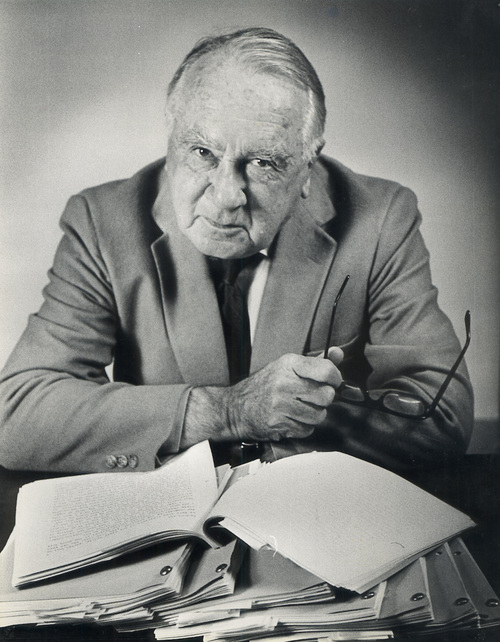

"All the federal programs would push our budget out of whack. That's been a perennial problem," said Norm Bangerter, who served in the Legislature in the mid-1970s and was Utah's governor from 1985 to 1993.

"We always seemed to manage," Bangerter said, but as health costs soar and Medicaid demands a greater share of tax revenue, "it gets harder and harder."

Through the years, Utah's eligibility rules changed and enrollment fluctuated, but it generally grew in pace with the population. Some states have threatened to drop Medicaid — which has never happened — while others have expanded eligibility.

The biggest expansion came in 1997 with creation of the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

The economy was booming and President Bill Clinton's push for comprehensive health reform had failed. CHIP, seen as a concession, had bipartisan support, sponsored by Utah Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch and Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Ted Kennedy.

Hatch told The New York Times he was offering the legislation to prove that the Republican Party "does not hate children."

As a nation, he added, "we have a moral responsibility'' to provide coverage for the most vulnerable children.

He was attacked, however, by conservatives in Washington and Utah. The Eagle Forum branded him a "Latter Day Liberal."

Utah lawmakers "protested strongly against taking federal money for another entitlement program, and it wasn't certain how many children would qualify," recalls Rod Betit, who directed Utah's Health Department under then-Gov. Mike Leavitt.

The duo lobbied Congress to shoulder more of the funding burden, and to permit states to cap enrollment and model CHIP benefits on private insurance plans.

"Hatch and Leavitt were arm-wrestling over it because Kennedy didn't want to make concessions. But we were able to get the governors to push the issue [of flexibility]," said Betit. "That was the only way the thing got through the [Utah] Legislature. It passed by just a few votes [in 1998]."

—

'Spend it in a better way' • Today, Herbert is seeking flexibility from Washington to create a program lawmakers can support.

"He wants to bring some fiscal certainty to it and tie it to the private market," Betit said. "Those same kinds of dynamics are happening again."

Herbert wants the Obama administration to hand over Utah's share of federal expansion funds — about $258 million a year — to fund private coverage for 111,000 poor and uninsured.

The feds are offering to pay the full costs of added Medicaid beneficiaries for the first three years and no less than 90 percent thereafter.

A growing federal deficit heightens fears that may change. This winter, Utah House Speaker Becky Lockhart, R-Provo, rejected the idea of taking the new Medicaid funds, arguing, "It would be irresponsible for the state of Utah to perpetuate reliance on federal money and continuance and reinforcement of a socialized medical system."

Congress has never withdrawn or reduced Medicaid funding, and increased it to help states through recessions in 2002 and 2004.

And the Congressional Budget Office has determined, more than once, that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will reduce the deficit, and that repealing it would increase the deficit. That's because of a host of new taxes, predominantly on the health industry.

"Right or wrong," Utah leaders have the sense that federal and state budgets are more thinly spread today than in the 1990s, said Betit. "And there's the fear that once you start [an entitlement] program, you can't pull it back. It's politically not likely to happen."

Herbert has criticized the ACA and the federal government's failure to live within its means. But Utah is already sending hundreds of millions of tax dollars to Washington to pay for the ACA, he points out.

"That's our money; it's going back there for a specific purpose," he said. "We ought to take the money because I think we can spend it in a better way."

Twitter: @KStewart4Trib

Tribune archivist Ana Daraban contributed to this report. Herbert's 'Healthy Utah' proposal

Participants in the "Healthy Utah" plan envisioned by Gov. Gary Herbert would have to contribute an average of $420 a year toward their health care.

Some would face a work requirement. Low-income parents whose children are on Medicaid could get financial help to move the whole family onto a private health plan.

"On private insurance they can probably get better quality of care and will have more insurance choices to fit their unique [health] needs," Herbert said. "Nobody's getting a free ride; they've got to put skin in the game. It'll make for a better program with better outcomes and give us better bang for the buck."