This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Carbon County officials are looking for state funding to pave 34 miles of roadway through Nine Mile Canyon, home to ancient Fremont rock art and an industrial conduit serving a now-dormant drilling complex.

While Carbon and Duchesne counties say the project is needed to serve natural gas operations on the West Tavaputs Plateau, preservationists believe the real goal is to open a new route for hauling Uinta Basin oil to a proposed refinery near Green River.

Utah's Community Impact Fund Board on Thursday advanced a $5 million funding request for the project's first 11-mile phase to its priority list for consideration in October.

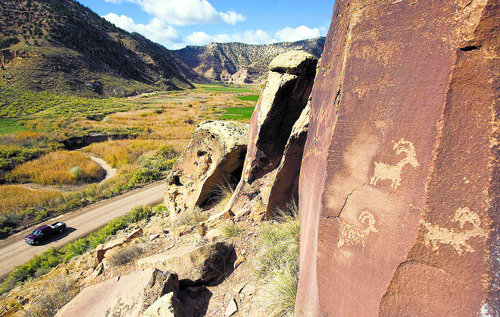

The county road, which leaves U.S. Highway 6 at Wellington, passes through an area rich in cultural resources and ancient rock art, which earns Nine Mile Canyon the nickname of "World's Longest Art Gallery."

Officials say the paving project is needed to reduce maintenance costs and improve access to approved gas-drilling projects held by the Bill Barrett Corp. and Gasco Energy. Yet neither company is actively drilling in the face of depressed natural gas prices. Meanwhile, Carbon County has just completed a $20 million surface-hardening project needed to protect the canyon's petroglyphs from road dust kicked up by truck traffic.

If Duchesne County paves the Gate Canyon Road south out of Myton, tanker trucks may soon have a fully paved shot to U.S. Highway 6, noted Dennis Willis, a board member of the preservation group Nine Mile Canyon Coalition.

"There is a concern of increased oil traffic. The concern is Gate and Nine Mile canyons will become a haul route to move waxy crude," he said.

Messages left with Carbon County commissioners weren't returned Thursday. In papers filed with the Community Impact Fund Board, officials made no mention of oil shipments, instead focusing on Barrett and Gasco's natural gas operations. This board disperses oil and gas revenue to municipalities for projects designed to address the impacts of energy development. The plan is to pave the road in three phases starting with the 11 miles above Soldier Creek Mine.

"This roadway is critical to both counties due to the significant benefits of natural gas development, cultural resources and other potential developments in the region," wrote Duchesne County official Edmund Bench Jr. in a May 29 letter to the impact board. Other papers say Barrett is "aggressively" drilling 80 to 90 wells a year on the Tavaputs, yet the company suspended drilling there a year ago after sinking about 200 wells in the first two years. Gasco, saddled with financial difficulties, has yet to start drilling.

Officials characterized the surface-hardening project as an initial phase of the road upgrade, which will cost another $17 million to cover in asphalt.

Bolstering the case that the project is about oil are recent reports from the Utah Department of Transportation, predicting a shortage of road space to move oil produced in the Uinta Basin.

A Myton-to-Wellington route through Nine Mile could alleviate truck traffic on U.S. Highways 40 and 191. But it would also further industrialize one of Utah's special places, according to Jerry Spangler, executive director of the Colorado Plateau Archaeological Alliance.

"That would sacrifice the cultural resources for industry because people wouldn't be able to enjoy them," said the expert in Nine Mile archaeology.

Spangler, who travels the 35 mph road about 25 times a year, says it appears to be in good shape and he has never seen a county road maintenance crew there.

Willis said he has seen vehicles traveling 70 mph on this road and suspects commercial haulers are already using it to avoid the port of entry and inspection station on U.S. 6.

"There is zero enforcement," he said.

To win approval for the West Tavaputs project in 2010, Barrett agreed to cover half the cost of the surface-hardening project. But county officials now say the 3/4-inch seal was never meant to be a permanent solution and truck traffic is taking a toll on the road.