This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Washington • President Barack Obama says he has a mandate from voters after winning re-election but Utah's members of Congress, too, say they have one from their own constituents and those agendas may not always line up.

Welcome to Washington dysfunction, 2013 edition.

Gridlock has described this town for the last several years — the most recent example being the showdown over the fiscal cliff — and it doesn't appear the polarization will lessen anytime soon.

"We have created a set of congressional districts, due in large part to gerrymandering, that means there are relatively few members of the Congress, of the House of Representatives, that are inclined to feel any urgency about accommodation or compromise," says Brigham Young University political scientist David Magleby. "And that makes governing pretty hard."

Indeed, this week's tumultuous battle over how to avert hikes on every taxpayer went down to the wire, and nearly fell apart amid rumblings by House Republicans that they would reject the final deal. Many members, including four of the five Utahns in Congress then, still ultimately voted no.

Worse, the deal really just punts more big decisions — such as raising the nation's borrowing limit and smoothing out spending cuts — for a couple months. Come March, Congress will again be taking the country to the brink of shutting down, or possibly, actual default.

A way of life • Sticking to campaign-style ideology in office has become more of a way of life in Washington, especially after the rise of tea party-backed Republicans and a left tilt for some Democrats. Taking a hard-line on issues, such as a GOP pledge against raising any taxes, leaves little room for negotiation.

"That assumes you'll get your way at all times but that's not life; that's not the legislator life," says Magleby. "We compromise."

Historically, there has been more ability to do so in Congress, with moderates bridging the gap between the two parties. But more and more of those members have lost tough elections, leaving, for example, only a handful of so-called Blue Dog Democrats like Rep. Jim Matheson of Utah who were the go-to bloc to make deals.

Matheson, who is now in his seventh term, agrees new, partisan congressional districts have produced members rigidly toeing a party line.

"They're more threatened by a challenge from a more extreme element in their party than they are by a general election challenge based on the way congressional districts have been set up across the country," says Matheson, who represents the most Republican district of any Democrat. "There's something to that that makes it more challenging to have consensus building."

Matheson notes that in his 12 years in Congress, he's seen the shift away from bipartisan compromises toward a strategy of simply trying to make the other side look bad.

"Something has got to give in this dynamic," he says.

The incentive, though, is lacking in many ways.

Lopsided elections • In Utah's case, Rep. Rob Bishop handily won re-election with more than 70 percent of the vote. New Rep. Chris Stewart claimed above 60 percent of the vote in his district.

And Rep. Jason Chaffetz swamped his opponent in the election, grabbing nearly 77 percent of the vote in his district and handing him, he believes, a reason to continue pushing the same ideals he has since first entering Congress in 2009.

"I'm going to fight for principle and not waffle day to day courting votes, and I think that's why I get such a strong percentage of the vote," says Chaffetz. "I'm not here just to oppose the president, I'm here to do what I think is right for the country and specifically Utah's 3rd Congressional District."

Chaffetz has crossed over to co-sponsor some legislation with Democrats in his time in the House but he says there are some issues where there is no room to move.

"I'll buck up against my party, I have many times, but we have to cut spending," he said. Most members express a similar perspective.

Sen. Orrin Hatch, who is in, he says, his final term in the Senate, was the only vote in Utah's delegation for the fiscal cliff bill, and he argues that the deal was a "perfect illustration of how compromise does happen."

"I'll take tax cuts for 99% of the people any day of the week rather than go off the cliff and not get anything," Hatch says. "Compromise has to be part of the system but it ought to have reason to it. That had plenty of reason to it, even though there's much of that bill I didn't like."

In the Senate of old, Hatch was one of those who forged compromises, including many with the late Sen. Ted Kennedy, such as the Children's Health Insurance Program and a national service initiative. But even Hatch, who is beginning his seventh term, says the body has shifted.

"The Democrats [have gone] more liberal, the Republicans more conservative," he says. "That's really what's involved here."

Mike Lee • Hatch's new Senate colleague, Sen. Mike Lee, is a good example. Vaulted into office by the rise of the tea party, Lee has stood strongly against Democratic efforts in his first two years and at one point held a lonely vigil against every single presidential nominee in protest.

Still, Lee says, it's not a given that Congress will reel from impasse to impasse.

"Compromise is a necessary, indispensable, and I believe ultimately inevitable part of any legislative exercise," Lee said. "I don't believe compromise is a dirty word."

His solution? Return to the previous process where legislation is introduced, heard in committee, amended and debated on the floor instead of the current route where bills are written in back rooms and changes strictly controlled.

"The best way to get bipartisanship and the best way to get genuine compromise ironed out under the light of day is to have an open amendment process," Lee says.

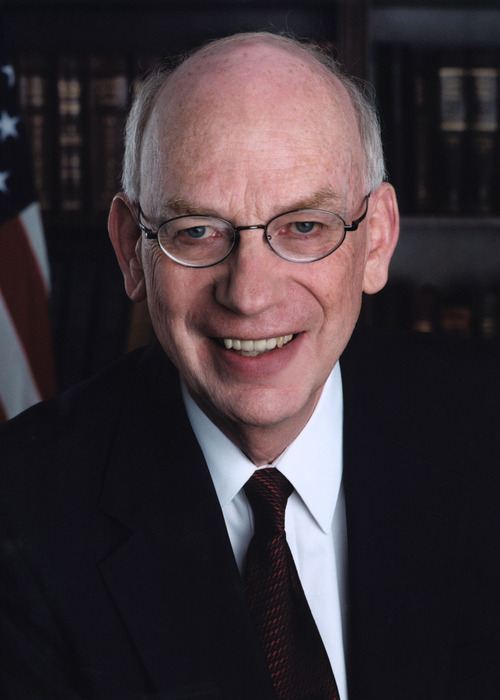

Interestingly, that's the same point stressed by Lee's predecessor, former Sen. Bob Bennett, who also saw the growth in the partisan divide during his waning years.

Bennett offers up a prime example of how the old system worked better: When Salt Lake City was in desperate need of a new federal courthouse, he went to the mat and worked with Democrats to ensure the money ended up flowing to Utah instead of to a project in Los Angeles not even yet in the planning stages.

"In that atmosphere, you can do that, but today because regular order has broken down those kinds of relationships that you build with cooperation are gone and as a result the decisions get made by the Executive Branch," Bennett says. "As a consequence, you get bitter feelings all around and no motive for people to work together because everything is going to get decided [at the White House] anyway."

Out of the Senate and in the private world of consulting and lobbying, Bennett says he's optimistic cooler minds will prevail with the new House and Senate and with Obama's second term.

"The problems are serious enough that serious people will emerge, and they will emerge as leaders and pretty soon one party or the other will begin to coalesce to solve our problems," Bennett says. "I think there are people in the Senate who are capable of coming forward and saying, 'OK, you guys have had your fun. Now, let's get serious.'"