This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

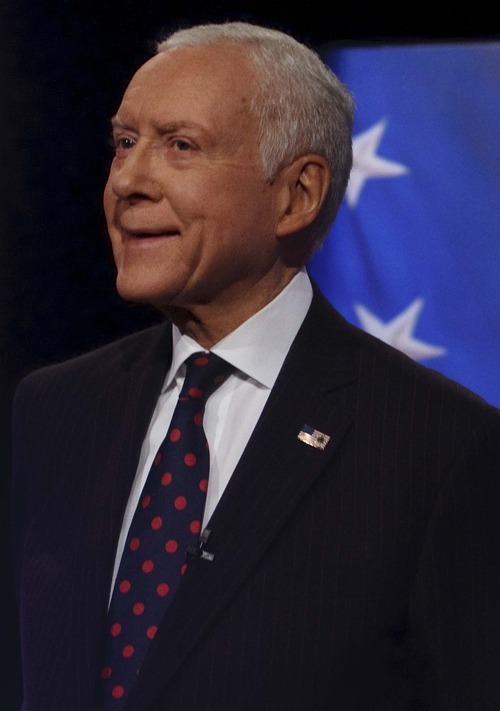

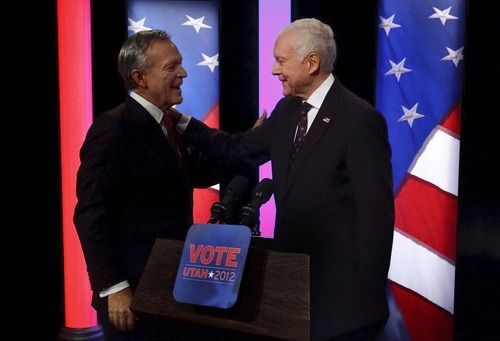

Sen. Orrin Hatch and Democrat Scott Howell agree on what the major issues are in their race: the value of seniority, Hatch's age, the big special-interest money that is funding Hatch — and what it all may say about how well Hatch is able to represent the average Utahn.

They just happen to disagree totally on each point.

Hatch says his seniority will allow him to lead the GOP's fight over the nation's toughest problems by possibly becoming chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Howell says Hatch's 36 years in Washington are far too long, and at age 78 Hatch is also too entrenched in the ways of Washington — and change is needed.

Howell says the record $11.7 million that Hatch has spent in the race shows that he's beholden to special interests, and has forgotten who he's there to serve. Hatch says it shows he has a national reputation for getting things done, and people throughout the country want to help him. He adds he knows Utahns well through his long service.

"I like to talk about experience. I have the respect of my colleagues. I will have a position of power where I can get things done for the people of Utah and the nation," Hatch says. "As long as I'm in the Senate, I will work my butt off."

Howell isn't impressed.

"When your heart and soul is bought by someone else, you can't be loyal to the average Utahn," Howell says.

—

Roots • Both men have been giant killers at times who challenged and beat longtime incumbents. Now, Hatch is the formidable incumbent who Howell is challenging in a rematch of their 2000 U.S. Senate race, when Hatch beat Howell with 66 percent of the vote.

Howell — who just retired after 34 years as an IBM executive — fell into politics and his first giant-killing encounter when he moved back to Utah after working in Atlanta. He took a young son to kindergarten, and found 32 other kids in the class.

"I asked if they were combining classes that day," he said. The teacher responded that no, classes are large in Utah. He complained to vneighbors that their children were being cheated out of a quality education. "They said why don't you do something about it?"

So he ran for the state Senate against an entrenched incumbent to fight for more school funding.

He knew something about fighting, having been a starting guard in football at Skyline High and Dixie College even though he weighed only 165 pounds. "It was pure determination and attitude," he said. Howell says he used that sort of effort to win the race, then two years later win election as Democratic leader in the Senate — a post he held for eight years.

Hatch first ran for the Senate in 1976 as a relative unknown, although he was a successful trial lawyer who had moved from Pennsylvania. "I thought [Democratic Sen.] Frank Moss voted too liberal to represent a state like Utah." The more he thought about it, the more he wanted to run.

He overcame better-known Republicans in the convention and primary with fiery speeches. Then he beat 18-year incumbent Moss by arguing not only that he was too liberal, but that he had been in Washington too long.

—

Mentors • Howell and Hatch both had some well-known mentors in their youth who convinced them that they could make a difference.

Hatch's family was poor in Pittsburgh and lived in a house that Hatch's father built out of scrap materials. But Pittsburgh Pirates star Vernon Law, a fellow Mormon, often stayed with them in his early career. He took an interest in young Hatch, and often took him along to religious firesides and speeches.

"He made me believe I could be somebody," Hatch says. That became powerful when combined with effects of an early shock in Hatch's life. He remembers a day he heard his mother screaming as she was told his older brother was missing in action (and later found dead) in World War II. Hatch says the shock made a permanent white streak of hair appear overnight when he was 10 years old.

It made him want to live two lives in one. Hatch says ever since he has tried to work twice as hard at anything he does.

Howell was raised in the LDS East Mill Creek 12th Ward where he rubbed shoulders with and was taught by such people as philanthropist O.C. Tanner and food bank founder Lowell Bennion. But he said more influence there came from Gordon B. Hinckley, then an LDS apostle who later would become church president.

"We had a quick relationship and bonding," Howell says, and adds they even talked in Hinckley's backyard about topics including "politics and giving back."

Howell says years later he mentioned to Hinckley that Republicans were courting him to switch parties when he served in the state Senate.

"Without flinching, he said, 'Scott, you will not join that Republican Party. We need good men and women in both parties. It does us no good to align with one political party. You can tell everyone you see that we are not a Republican church,' " Howell says.

—

Seniority • While their backgrounds make both value public service, the pair now see the value of seniority differently.

Howell recalls the president of his LDS mission imparting an important lesson when Howell questioned why he had been named senior companion to a missionary nearing the end of his service. "He said, Scott, seniority is not about age or time in service. It's about leadership, creativity, innovation."

He remembered that later in life when IBM sent him to manage more senior employees to try to turn around some underperforming units.

"IBM has very little appetite for those who don't perform," he said. So he adds, "I just can't imagine we're going to send back a guy who's been there 36 years" after he "voted to raise the debt ceiling 16 times" while vowing to cut spending and reduce debt.

Howell not only wants to get rid of Hatch, but also some Democratic leadership that he sees as part of the problem — including Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev. "Harry Reid has to go. ... When I get back there, we're going to have new leadership."

Meanwhile, Hatch says his long service is finally putting him in a real position of power. He is the GOP leader of the Finance Committee, and could become its chairman if his party wins the majority in the Senate.

"It's the most powerful and influential committee in the Senate," he says. "It often takes years just to get on the committee."

Hatch said the position will give him a chance to play a key role in reforming entitlement programs like Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, and overhauling health care and the tax code. "About 60 percent of all federal spending goes through that committee."

—

Big money • Hatch has raised and spent more than $11.7 million on this Senate race, or 48 times what Howell has managed to raise.

"You look at where his funding has come from, and Orrin Hatch is not being run by his constituents. He's being run by big dollars," Howell says. In contrast, tears come to his eyes when he talks about how a disabled man gave him $100 over his objections as he said he wanted someone who would represent him.

"That made me very emotional and made me realize what's going on in America today," he said. "It's eliminated those who want to serve because they don't have rich and powerful friends."

Hatch sees it differently. "Nobody expects me to do their bidding [because of donations]. They know me better than that," he says. "I hate to raise money here [in Utah] because a lot of people pay tithing" and other church contributions, "and I'm real reticent to ask them, but I've had significant support in this election."

—

Too far right? • Howell contends that Hatch moved far to the right in this election to try to appease tea partyers who helped defeat Sen. Bob Bennett two years ago. He charges that has contributed to gridlock, making Hatch hesitant to work with Democrats because it could upset hard-line conservatives.

"We've got to send people to Washington who value the way we want politics done, and truly that means electing people who are willing to reach across the aisle and always put people first," Howell says. "He sold his soul to that tea party group."

Hatch says his record is plump with bipartisan accomplishments, including working with liberal former Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Mass., and Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., to find compromise and pass bills on children's insurance, generic drugs, dietary supplements and even the Religious Freedom Restoration Act.

Howell, age 59, created a stir in the race with a fundraising letter that suggested Hatch was too old to serve, and could die or become disabled in the next term.

"That's a desperate comment by a desperate campaign," Hatch said. "That's an insult to people who have ability and a lot of years to live." He insists he's in great physical and mental shape, "and I don't know anybody that works as hard as I do."

Hatch has vowed that he will not seek re-election after this term.

Howell said he brought up age because Hatch had attacked Moss back in 1976 over age and his length of service, and had said in writings and speeches through the years that he planned to retire before now.

"I'm not going to be 78 and running for the Senate," Howell vowed. "I'm going to go back for two terms, get in and get out and come back." U.S. Senate race

Sen. Orrin Hatch, Republican

Served 36 years in the Senate, after first being elected in 1976.

Former chairman of the Senate Labor and Judiciary committees. Currently ranking Republican on the Finance Committee.

Ran unsuccessfully for U.S. president in 2000.

Former trial lawyer.

Wrote many song lyrics that have been recorded. His song "Heal Our Land" was performed at President George W. Bush's 2005 inauguration.

Scott Howell, Democrat

Served 10 years in Utah Senate, including eight years as its Democratic leader.

Recently retired after 34 years as an IBM executive.

Ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate against Hatch in 2000.

Won football scholarship as an offensive lineman to Dixie College, even though he weighed only 165 pounds.

Says when GOP tried to get him to switch parties, former LDS Church President Gordon B. Hinckley talked him out of it.