This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Washington • Four years ago, Mitt Romney arrived in New Hampshire, his usually perfectly coiffed hair slightly disheveled and his mood a bit depressed after coming in second in the Iowa caucuses.

"Well, we won the silver," Romney told supporters, who, despite their zeal, couldn't wrestle up enough votes to win the Granite State's primary days later.

Always the optimist, Romney pressed on, noting that like in the Olympics, when you don't win your first time around, "You come back and win the gold."

This week Romney will take the stage in Tampa, Fla., before thousands of enthusiastic delegates and lay claim to the GOP's top prize: the party's nomination for the presidency.

It's the coveted spot that Romney has fought for, arguably, for more than six years, and one that his father sought and failed to obtain more than four decades ago.

Friends and advisers to the presidential candidate say that his late father's advice after his own disappointing loss still helps Romney bounce back after faltering and keeps him pushing forward.

—

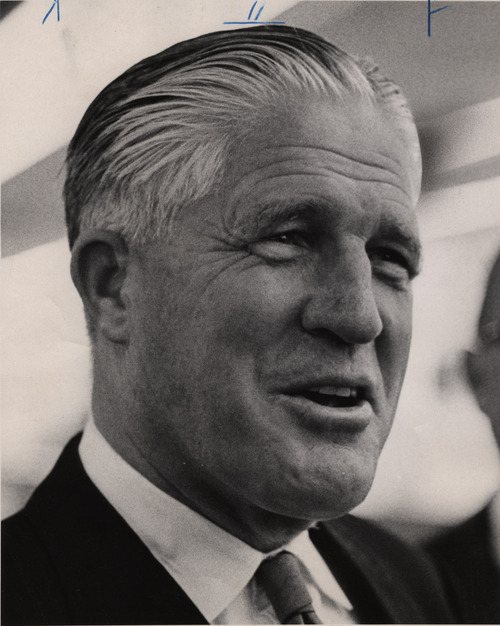

Family code • In 1966, after George Romney won a second term as Michigan governor in a landslide, boosters started cheering him on for higher ambitions.

"Romney's great — in sixty-eight," they chanted, hinting at a 1968 presidential run, according to the book George Romney, Mormon in Politics by Clark Mollenhoff.

A Gallup poll at the time showed Romney within striking distance of President Lyndon Johnson (who hadn't yet announced he would not seek a second term), and a Harris poll later gave him a 10-point advantage over the Democratic incumbent.

Then, the trouble started. The conservative wing of the party raised questions about Romney's more liberal Republican leanings, and Democrats piled on, according to the biography.

Ultimately, it was Romney's own comment — and the hype it received — that brought his White House hopes to an end. In an interview with a Detroit radio station, the host pressed Romney on his apparent inconsistency on Vietnam.

"When I came back from Vietnam [for a fact-finding trip], I had just the greatest brainwashing anybody can get," Romney said, uttering the word that would doom his chance at the presidency.

At the time, Mitt Romney was serving a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in France and heard about his father's loss in a letter.

"Your mother and I are not personally distressed. As a matter of fact, we are relieved," George Romney wrote on the last page, according to Time magazine, which dug up the letter a few years ago.

"We went into this not because we aspired to the office, but simply because we felt that under the circumstances we would not feel right if we did not offer our service. As I have said on many occasions, I aspired, and though I achieved not, I am satisfied."

Mitt Romney noted the latter phrase was a favorite of his mother, Lenore Romney, and one that she used when she lost her own bid for a Senate seat from Michigan in 1970. But it was another famous quote by an ancient Jewish leader that Lenore Romney often cited that rang out for her son.

"If not me, who? If not now, when? If not here, where?" Romney quotes his mother as saying in his own book, Turnaround.

It was Mitt Romney's turn in 1994 when he took on a dynasty, Sen. Edward Kennedy in his home state of Massachusetts. Romney lost but continued on in the business world until another opportunity opened: The 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City.

Romney is credited with turning those Games from scandal to success and parlaying that into the Massachusetts governorship.

Kevin Madden, a senior adviser to Romney's campaign, says the candidate often draws on his family's experiences in politics — successful and not — and that Romney himself has followed his father's path from business to public service.

"It's part of the Romney code: to those that are given much, much is expected," Madden says. "Drawing upon the six years I've known him, that's how he was brought up. Those principles were instilled in him at a very young age."

In 2007, Romney took his first plunge himself into the challenging waters of the presidential race.

—

The first try • One poll, coming days after he announced an exploratory committee, showed that about 4 percent of Americans knew who Romney was.

Romney plunked down tens of millions of his own money to expand his name ID, even paying for straw poll voters to swing his way. But there were definite moments when the campaign struggled.

Madden, the Romney adviser, says the ex-governor's fortitude kept the campaign alive.

"I think he actually got the strongest when these campaigns have been at their lowest moments," Madden says. "That's where he's had an incredible effect on the entire organization. The campaign reflects his attitude."

After 2008 losses in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Florida, Romney finally won Michigan, where he was born and where his family name was still revered.

Super Tuesday, though, was the death knell. Romney put on a brave face at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington where he pulled out of the race and stood behind the eventual nominee, Sen. John McCain.

Years later, McCain returned the favor, endorsing Romney on the eve of the New Hampshire primary that Romney this time would win in a walk.

Another senior adviser to the Romney campaign, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he wasn't authorized to speak by the campaign, says the ex-governor's withdrawal from his 2008 bid helped attract supporters this time around.

"I think in the end people do reward persistence," says the adviser who has worked with Romney for years. "They want to see him get knocked down and stand back up, and the fact is we did that, didn't run away, [played] the big boy, took our medicine and came back and worked very hard for McCain in '08 and others in 2010. This is how he was prepared to pay the price and go the distance."

Republicans, traditionally, have rewarded candidates the second time around on the national stage, but that doesn't mean Romney was going to have the nomination bequeathed to him.

—

The gauntlet • Like his father before him, Romney entered the 2012 race as the likely front-runner. He had the experience from his first run, the veteran team and the money tree ready to shake.

But Republican voters weren't quite sure they wanted Romney. In fact, it seemed like they wanted to dance with everyone else before settling on him.

First, it was Minnesota Rep. Michele Bachmann who won the Iowa straw poll and bounded to the front of the line. Texas Gov. Rick Perry drew high interest when he entered the race until he uttered the debate "oops" heard round the world.

Businessman Herman Cain won November's poll numbers, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich owned December and ex-Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum came from behind in January.

Romney, though, stayed consistent and started racking up delegates and avoiding the story of the day to focus on the economy as the main, and sometimes single, theme of his campaign.

"There's always this sort of fascination with the next one, and the fact is we were a campaign that was organized to win the nomination, not win the month of November 2011," says the Romney senior adviser who spoke on condition of anonymity. "And you have to let that play out."

In debate after debate, Romney often stayed clear of attacking his opponents and instead laid siege to President Barack Obama's policies. Ignore the others on the stage, Romney's strategy suggested, this is between Obama and me.

"I think now, given what America is facing globally, given an economy that has changed its dynamics dramatically over the last 10 years, you need to have someone who understands how that economy works at a very close level if we're going to be able to post up against President Obama and establish a record that says this is different than a president who does not understand job creation," Romney said in an ABC News debate in New Hampshire.

Romney's well-funded campaign, helped along by a super political action committee forking over millions, put staffers on the ground and commercials on the air. His team was unmatched in the GOP field, and by mid-May it had outlasted any major competitors.

While Romney suffered his own gaffes — such as calling corporations people or noting that he liked to be able to fire people — the news cycle burned through those slip-ups quickly and moved on, unlike in his father's day.

Kirk Jowers, a Romney friend and supporter and head of the University of Utah's Hinckley Institute of Politics, says Romney followed a path similar to his father's but with the added bonus of not having to blaze it.

"He saw his father's success in politics and public service, so he saw how much could be accomplished," Jowers says. "I'm sure he absorbed a lot of lessons from his parents' losses, but there have been so many successes as well that he certainly had a balanced view."

Romney, in an interview with MSNBC aired Friday called his dad a "huge presence in my life. … I wish he were able to see what I'm up to right now."

Thursday night, on the stage with a backdrop built to look like a wall of family photo frames, Romney will be crowned the GOP nominee.

For Romney, the images likely are more than a politician's prop.