This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

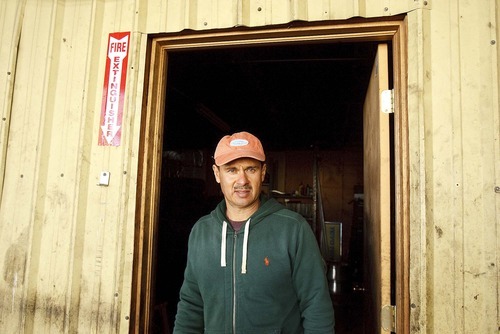

Gerardo Avilos is surrounded by tires. Big ones and small ones, new ones and used ones — stacked so high inside a garage bay that it's hard to tell where the black rubber ends and the back wall begins.

His business is getting people on the road again and, for the past 11 years in Salt Lake City, it's where he has spent every day except Sunday supervising four employees replacing tires and repairing engines.

But Avilos knows that there wouldn't be a Mexico Tires and Auto Repair if it weren't for the events of Nov. 6, 1986.

"Everything was different," Avilos said. "I felt kind of free, you know?"

The 46-year-old with green eyes, a brown moustache and a quick smile paused, remembering the long-ago moment with clarity. It was that day when, with the stroke of a pen by President Ronald Reagan, Avilos was put on the road to citizenship.

Even mentioning Reagan's name makes him emotional.

"A great, great man," Avilos said. "He had compassion. He understood."

Today marks the 25th anniversary of Reagan signing a landmark bill that granted legal status to almost 3 million undocumented immigrants in the United States. It was legislation that was more than four years in the making and had been decried by critics as a disaster and lauded by supporters as the only reasonable way to deal with the undocumented immigrant population already living here.

Supporters point to people like Avilos, who opened a business, hired people and contributes to the economy. Opponents say it didn't work and simply opened up the border to an explosion of illegal immigration, which depresses wages.

But what everyone seems to agree on is this: Reagan's signing of the Immigration Reform and Control Act was the last major step taken by the federal government on an issue that seemingly won't go away.

—

A new law • According to the Pew Hispanic Center, the estimated undocumented immigrant population in the country was about 4 million around the time Reagan signed immigration reform into law.

In the center's latest estimation, that number has swelled to more than 11 million.

Those numbers tell the story of why Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, said he chose to vote against the bill in October 1986.

"I predicted if they grant amnesty, which they were honest enough to admit they were doing, we'd have millions more coming in," Hatch said. "Guess who won that argument?"

Hatch was in the minority, however.

The measure swept through the upper chamber 63-24 and by a 238-173 margin in the House of Representatives.

Sen. Alan Simpson, R-Wyo., was the chairman of the Immigration and Refugee Subcommittee and saw the legislation as a chance to normalize the lives of those living in the shadows.

"You can't just have this undigestible lump of 11 or 12 million people in the United States who are used, exploited and expendable," Simpson said. "That's the cancer."

The legislation, however, lost some teeth when it came to employer sanctions.

It was changed to level fines against employers of between $250 and $10,000 per violation — but only if the business "knowingly" hired undocumented immigrants.

He said that provision was undercut when the bill didn't require a proposed national identification card, which would've provided an easy way to verify a person's legal status.

Simpson said that part was removed largely because of a speech prior to the House vote given by U.S. Rep. Edward Roybal, D-Calif., who warned the country could "face the danger of ending up like Nazi Germany."

The Wyoming senator was incensed.

"And who in America would want a national ID card? That's what they did in Germany? I mean, honest to God," Simpson said, exasperated. "Well, that took care of that."

But the portion that remained permitted undocumented immigrants who had been in the country before 1982 to apply for temporary residency as long as they didn't have any felony convictions.

Within 18 months of being given temporary status, they could then seek permanent residency after satisfying a series of requirements, including minimal understanding of English and a knowledge of American history.

After five years, they could apply for citizenship.

Gerardo Oribios followed that path into the U.S. Army.

—

A new life • Oribios had come over the border at Tijuana illegally as a young teen and worked his way through parts of Southern California picking oranges until he decided to move to Washington state to harvest apples in the orchards.

But it was that summer, when "Top Gun" was setting box office records and Roger Clemens was pitching his way to a Cy Young award with the Boston Red Sox, that Oribios and friends heard another bit of news: There was a piece of legislation floating through Congress that would give them a chance at legal status.

"Everybody was excited by it," Oribios said.

And when the bill ultimately was signed, Oribios said it changed everyone's perspective. His friends started looking into being lawyers or immigration advocates. But Oribios wasn't quite ready to focus on a specific trajectory. Instead, he bounced from job to job until he moved to Utah in 1992 and decided to join the National Guard. It was then, when talking to soldiers, he thought he'd try to enlist in the U.S. Army. He scored well on the tests, was sworn in and sent to basic training.

"I went in and, man, what a feeling that was," he said. "I couldn't believe that I had just become a soldier. My lifetime dream was achieved."

Oribios became a paratrooper before settling in as a civil affairs specialist stationed in Italy.

The 40-year-old father of three, now a staff sergeant, said in an email interview he has been struck by two key moments in his life: the day he was sworn in as a U.S. citizen during a Salt Lake City ceremony in 1996 and when he decided to make his career in the military.

"Being in the Army," he said, "has given me the satisfaction of somehow being able to repay my adoptive country for all of the good things it has given me."

Oribios' story wouldn't surprise Simpson.

The retired senator said he still runs into people who were granted legal status through the legislation and will be greeted with calls of "Viva, Simpson" when he's traveling.

But he said he doesn't care about the credit. Those who grabbed the opportunity afforded in the Immigration Reform and Control Act are the ones who deserve praise, he said.

"Don't thank me, thank yourselves," Simpson said. "You were given the chance, and you made it. I opened the door a crack, and you blew the hinges off and made yourselves great Americans."

—

A different time • The signing of the legislation in the White House's Roosevelt Room came just about a week before Reagan would admit to selling arms to Iran in exchange for the release of American hostages — a scandal that rocked his presidency and dominated headlines.

The immigration-reform signing ceremony that Thursday morning took less than a half-hour. Reagan delivered a few remarks as he was flanked by a broad spectrum of politicians, from conservative Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., to liberal Rep. [now Sen.] Charles Schumer, D-N.Y. Vice President George H.W. Bush stood right behind the seated president.

"The legalization provisions in this act will go far to improve the lives of a class of individuals who now must hide in the shadows, without any access to many of the benefits of a free and open society," Reagan said. "Very soon many of these men and women will be able to step into the sunlight and ultimately, if they choose, they may become Americans."

U.S. Rep. Romano Mazzoli, D-Ky., was the House sponsor of the bill and stood by as the president signed it into law.

Mazzoli said he took heat for sponsoring the bill, namely from the AFL-CIO, which had been a vocal opponent, using a series of protectionist arguments.

"It made for some tough elections," Mazzoli said. "But then again, I was the only guy in a tobacco patch who voted for a ban of smoking on airplanes, too."

The 79-year-old retired lawmaker, who just completed a six-part presentation on immigration at the University of Louisville, said the current political climate on immigration would make it difficult to pass similar comprehensive reform today.

But Mazzoli said he'd attempt to do it again because of what he sees are the fruits of the legislation.

In 1996, he recalled being in El Paso, Texas, where 3,000 people were sworn in as citizens. He said several he met there were either beneficiaries of the Immigration Reform and Control Act or relatives of those who benefited.

"They came up to me and told me how it had helped them," Mazzoli said. "I had no idea at the time [in 1986] that I'd meet so many wonderful people that would yield such wonderful memories."

—

A 'huge mistake' • William Gheen sees it all differently.

The founder of Americans for Legal Immigration PAC, centered in North Carolina, said the entire bill was a sham from the beginning.

"Reagan made a huge mistake in giving amnesty to 3 million illegal aliens on the promise of future enforcement and now we have 12 to 20 million in this country," Gheen said. "God knows how many are dead and suffering because of his mistake or betrayal — I'm not sure which it is since I can't judge his heart."

Gheen said a key advantage advocates for the bill had in 1986 was the absence of the Internet and a dearth of vocal groups opposing amnesty. At the time, the only national organization fighting the legislation was the Federation for American Immigration Reform, commonly known as FAIR.

"If we had the Internet in its current form and more groups like ours joining FAIR, it wouldn't have passed," Gheen said. "I guarantee if we could use the communication tools we have today and could tell people that 1 million getting amnesty would become 3 million and that now it would be 12 to 20 million, that bill would've been stopped."

"We have helped defeat these amnesty bills over the past six years," Gheen said. "We will continue to do so."

Edwin Meese, who was Reagan's attorney general at the time of the bill's passage and signing, said he supported the president then but wrote in a 2006 opinion piece in the The New York Times that revealed his thoughts about its failings.

"From the start, there was widespread document fraud by applicants. Unsurprisingly, the number of people applying for amnesty far exceeded projections," Meese wrote. "And there proved to be a failure of political will in enforcing new laws against employers."

But some opponents at the time of its signing have since flipped their view on the bill, too.

The AFL-CIO, for example, now is in line with the Service Employees International Union in pushing for new immigration reform that would provide a pathway to citizenship.

—

States step out • In the absence of comprehensive immigration reform for the past quarter century, states such as Utah, Arizona and Alabama are taking stabs at leading out on the issue — all with enforcement-only laws on the books and Utah adding a guest-worker law.

Each of those states is defending the enforcement-only laws in court. Utah's guest-worker law — which would allow undocumented immigrants to pay fines and pass background checks in exchange for a legal work permit — isn't slated to take effect until July 2013.

Hatch said he understands why states are moving forward.

"When states have criminals coming across the border and killing their citizens," Hatch said, "and the federal government isn't doing the job, I really believe there is a considerably good constitutional argument that states ought to be able to protect themselves."

Reagan, in his remarks at the 1986 bill signing, expressed a more optimistic view.

"Future generations of Americans will be thankful for our efforts to humanely regain control of our borders and thereby preserve the value of one of the most sacred possessions of our people — American citizenship."

dmontero@sltrib.comTwitter: @davemontero