This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Utah sued the Obama administration Friday over its new "wild lands" policy, becoming the first among several like-minded Western states to attempt to block "virtual wilderness" designations.

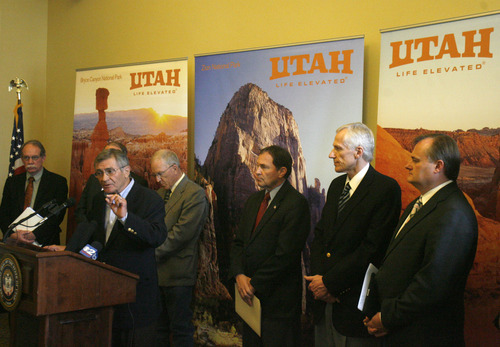

Gov. Gary Herbert announced the lawsuit Friday at the Utah Capitol, saying that he expects Alaska to do the same, while Idaho and Wyoming could join the Beehive State's case.

Herbert warned that the wild lands policy creates a category of lands akin to wilderness without going through the proper congressional process. That puts a drag on resource development, he said, and "is not good for Utah. It's not good for America."

"Some would like [lands] to be a single use: all wilderness, all just backpackers," the governor said. "That's wrong."

Wilderness areas bar motorized access and many forms of resource development but allow primitive recreation and livestock grazing.

The Utah Attorney General's Office filed the lawsuit against the U.S. Interior Department in Salt Lake City's federal court.

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar announced the hotly disputed plan in December. It calls for a new inventory of roadless lands with wilderness characteristics that could be administratively protected.

John Swallow, Utah's chief deputy attorney general, called that "virtual wilderness."

"Congress," he said, "and not the executive branch, has the right to designate wilderness."

John Harja, the governor's public lands policy coordinator, added another legal theory that the case will test: Wild lands are effectively an amendment to the Bureau of Land Management's area management plans without the usual years-long public process to determine appropriate uses.

The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance rejected those arguments and predicted a judge likely would toss the case.

For starters, SUWA attorney Heidi McIntosh said, the wild lands policy hasn't even resulted in any acreage being managed differently. If an inventory identifies new areas to protect, she said, the BLM then would gather public input.

The court likely would find the lawsuit premature, she said, "because they don't even have anything to complain about."

Utah also argues that Salazar's move violates a congressional mandate to identify potential wilderness areas by the early 1990s. The lawsuit contends all such studies were to end then, although McIntosh said that first inventory was simply a mandatory starting point.

Interior spokeswoman Kendra Barkoff declined to comment on the state's lawsuit. But she provided an April 15 email from BLM headquarters to senior land managers instructing them to back off from "any activity that could be construed as implementing" the wild lands policy, due to the congressional action earlier this month striking funding for the program.

State officials point out that the defunding decision affects only this year's budget.

Salazar's policy appears to have legal backing in the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act, according to University of Utah law professor Robert Keiter, who teaches public lands and natural resource law. That act calls for constant inventory of lands for possible management shifts to "reflect changes in conditions and to identify new and emerging resource and other values."

"The secretary is probably on fairly firm footing," Keiter said.

Peter Metcalf, president of Utah-based Black Diamond Equipment and vice chairman of the Outdoor Industry Association, said the state's move makes no economic sense. His company employs 250 Utahns, he said, and the twice-yearly Outdoor Retailer shows bring $40 million to the state, all in the name of "human-powered recreation."

The retailers show nearly pulled out of Utah when then-Gov Mike Leavitt negotiated an end to wilderness inventories, he said, referring to a deal that Salazar's rule effectively ended.

"This is extreme," Metcalf said of the suit. "This is a power grab by the state on behalf of extractive industries."

Herbert, who collected at least $396,000 in campaign contributions from energy companies during his 2010 election campaign, recently released a 10-year energy plan that leans on traditional fuels from federal lands while promoting renewable-energy development.

He said Friday that Salazar's policy is "like throwing a monkey wrench in the gears" of energy development.

County commissioners from Uintah and Washington counties joined the governor to back the suit.

Uintah County, chief among the state's natural-gas producers, feels threatened by a potential reversal of a 2008 BLM plan for the Vernal area designating lands for energy development. The uncertainty could chill companies that otherwise would seek drilling permits, Commissioner Mike McKee said.

"With investment," he said, "there has to be some kind of predictability."

Washington County, a pioneer in the state's single-county approach to wilderness, fears Salazar's policy means the 2009 bill that designated wilderness in Utah's Dixie won't be the final word.

"We were excited to have wilderness behind us," Commissioner Alan Gardner said.

Ted Wilson, Herbert's environmental adviser, said he is a wilderness advocate, but backs the suit because "these counties need a place to make a living."

Herbert said Salazar's policy "threw a wet blanket" on negotiations in other counties to work out wilderness designations. San Juan County's talks are furthest along, with potential to protect places such as Cedar Mesa while penciling in others for resource development.

Those talks have continued, though, with county officials saying they are committed to the process regardless of the wild lands controversy.

The Wilderness Society's Utah director, Julie Mack, agreed Salazar's policy injected some uncertainty in the process, but said the suit could add more.

"I hope," she said, "that this decision that the state has made won't further threaten that climate that we need to collaborate in or to move forward."

twitter: @brandonloomis —

The Leavitt deal

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar's wild-lands policy essentially set aside a 2003 agreement negotiated by then-Utah Gov. Mike Leavitt with the Bush administration to take away the authority to identify new areas with wilderness potential.

It could affect 6 million roadless acres in the state, including spots such as Cedar Mesa, Desolation Canyon and the San Rafael Swell — all in eastern and southeastern Utah.

Utah officials, including the congressional delegation, have scoffed at Salazar's plan. Rep. Rob Bishop, R-Utah, helped strip this year's program funding from the budget, and Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, said Friday he is working on legislation to "release federal lands from wilderness protections."