This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Vineyard • Wayne Holdaway is like many old-timers who never imagined the future that is swiftly unfolding just to the north where Utah's Geneva Steel once stood.

In a few short years, a huge development at the site will transform his hometown with a pulsing 1,700-acre complex of houses, apartments, town homes, stores, offices, factories, school buildings and a new town center.

Vineyard is expected to mushroom from about 465 residents to as many as 27,000 in less than a decade as a shortage of developable land and booming real-estate markets drive one of the most ambitious projects seen in Utah County. That's a growth rate of more than 5,700 percent.

The development, dubbed (at)geneva, is meant to bring new life and value to one of the largest U.S. brownfields west of the Mississippi River.

"Rather than fence this thing off and let it become a big weed patch for the foreseeable future, we are taking the responsible approach of repurposing and rebuilding what was an old steel mill," said Stewart Park, project manager for (at)geneva on behalf of Sandy-based Anderson Development.

Today, construction crews are finishing the first homes and paving the initial roads into what is envisioned as a blend of residential, commercial and industrial buildings worth upward of $3.2 billion. Final totals on office and retail space alone could top 5.6 million square feet, comparable in span to 30 Wal-Mart Supercenters.

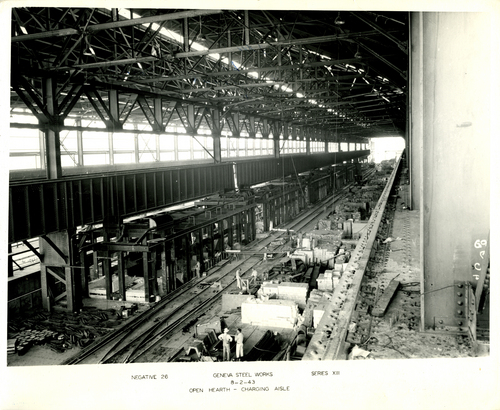

Holdaway, 77, marveled as a young boy at the Geneva mill's mammoth presence, its smokestacks and its World War II-era military features — back when dairy farms and steel production defined that corner of Utah County. Most area residents grew up either working the fields or smelting and rolling sheets of hot metal.

"This was always farm country," recalled Holdaway, who lives along Vineyard's Holdaway Road, named for descendants of pioneer prospector and polygamist Shadrach Holdaway. "If we had our way, we would still be a farm community. But it's progress and I realize that."

—

Talk of the town • Though much of the former mill site spreading west from Geneva Road to Utah Lake remains rubble and dirt, (at)geneva's plans are dramatic — even for a county of 552,000 whose population swelled by 6.8 percent just from 2010 to 2013.

Land-use blueprints call for single- and multifamily housing, lakefront properties, commercial districts, corporate headquarters, a Utah Valley University satellite campus, Larry H. Miller Megaplex Theatres, a transit hub centered on FrontRunner and, perhaps, TRAX, three Interstate 15 interchanges, nine stoplights and a town center rivaling those in nearby Orem and Provo.

Managers with Anderson Development, which acquired the site for $46.8 million in bankruptcy proceedings in 2005, are moving fast these days. More than half the roughly triangular (at)geneva footprint has sold to future builders, said Park, with many remaining parcels under contract or getting multiple bids.

Sentiments in Vineyard's older southern quarter have evolved since Anderson's master-planned project first took shape.

With only a handful of full-time employees, town hall relied heavily on the company in creating a new zoning master plan. The powerful developer pitched, pestered and pleaded with elected leaders along the way. It has lobbied county and state officials and lured major players into (at)geneva with sweet land deals. At one point, frustrated with the Town Council, company officials explored carving the entire site out of Vineyard's boundaries and annexing it into adjacent Orem or Lindon.

Anderson and town officials both say their dealings are cooperative these days. Longtime Town Council member Sean Fernandez said Vineyard's leaders, for their part, have scaled a steep learning curve.

"For a long time we were somewhat skeptical, but we've really embraced it and tried to make it a nice development," Fernandez said. "It's a huge deal, especially for the residents who have grown up in Vineyard."

The mayor and four-member council reluctantly created a Redevelopment Agency, or RDA, letting Vineyard bond for more than $300 million to put toward cleanup, developer incentives and new water, sewer and road amenities for the project.

"There was lots of whooping and hollering around the office that day," Park said.

The town's RDA debts will be paid off in increments with new tax monies drawn from (at)geneva's upward impact on the site's property values, part-time town planner Nathan Crane said.

"We've been very careful not to overextend ourselves," he added.

With Vineyard Elementary its only public school, the town also agreed to pay one-time mitigation fees to Alpine School District should the influx of new students from (at)geneva skew the district's bottom line.

Many predict (at)geneva could pump up the area economy as much as Geneva Steel did in its heyday — or more — and without the air pollution that once belched from the mill and clung to the sky.

"It has the potential," explained Utah County Commissioner Larry Ellertson, "to build a good commercial base, add jobs and contribute with a reach far beyond that town's borders."

—

Concrete jungle • Federal law mandates ongoing review of the site by the Utah Department of Environmental Quality, a legacy of six decades of mill operations. Contrary to dire predictions a decade ago, less than half the acreage has proved polluted enough to warrant regulatory concern, according to DEQ environmental scientist Rocky Stonestreet, who helps oversee the Geneva cleanup.

DEQ notes the polluted areas— about 140 waste-management units within the site — show varying levels of contamination from volatile organics, heavy metals, petroleum byproducts and other potentially health-threatening compounds.

With state regulators looking over their shoulder, Anderson Development and its partners spent seven years moving mountains of tainted soil, slag, building waste, scrap metal and other mill remnants while drilling scores of groundwater monitoring wells. Huge mounds of dirt have steadily piled up at the site's north end, where Anderson wants to put industrial buildings.

Some surprises emerged as the company inventoried pollution problems, Park said, but the worst headache has been concrete.

Lots and lots of concrete.

The U.S. government built the Vineyard mill as the country ramped up for World War II and located the factory inland partly to lessen the chance of a Japanese air attack. Holdaway remembers seeing anti-aircraft turrets at key positions around Geneva. Its underlying design, come to find out, reflected a similar fortress mentality.

When Anderson bought the site and a Chinese company, Qingdao Iron & Steel Group, stripped out mill equipment and shipped it to the Far East, initial estimates pegged the total volume of concrete at 150,000 cubic yards.

Crews already have pulled out 700,000 cubic yards — about 1.4 million tons — and new estimates are that's a third of what's there. In some places, abandoned building foundations reach 40 feet or more underground.

"They poured concrete for weeks and weeks and weeks," Park said. So much, in fact, Anderson moderated how it crushed and resold the material to avoid depressing statewide prices for road base.

Stonestreet with DEQ said the abandoned slabs also deeply complicate site cleanup, monitoring and modeling of how pollutants might leach into underlying water tables.

—

Town and gown • With the cleanup well underway and other components falling into place, Anderson now has what it portrays as something of a land rush on its hands. Parcel sales picked up dramatically in the past 18 months, Park said, as realty markets on the Wasatch Front continue to rebound.

Some would-be buyers are chasing UVU's decision to secure a second 125-acre piece in the core of the development, next to a 100-acre lot it purchased in September 2011. Eager to draw the surging school as a marquee tenant, Anderson Development donated half the first parcel's $20 million price tag.

"We can now call it a college town instead of an industrial park," said Gerald Anderson, the company's co-owner.

For the university's part, with little available land near its Orem campus, the (at)geneva add-on is seen as vital to accommodating student growth, UVU spokeswoman Melinda Colton said.

"It will essentially double our footprint in Utah County," she said.

UVU has already planted four intramural sports fields on its (at)geneva lots and is hiring consultants to help plan academic, athletic, housing and parking facilities.

Road access to (at)geneva led to it being eyed in 2006 as a potential Real Salt Lake soccer stadium site, before the team chose Sandy. Transportation is an even bigger selling point for it now.

Tapping redevelopment money, town officials are extending two roads, Main Street and Mill Road, northward into the project. The Utah Department of Transportation began work in July on a one-mile east-west highway segment steering Orem's 800 North west into the development and tying those two roads together.

"This is a huge benefit for the traffic flow through Vineyard," UDOT project manager Justin Schellenberg said. "It basically opens up the entire north area of their town.''

UDOT's work, he added, is the first phase of a four-lane arterial — akin to Bangerter Highway — called the Vineyard Connector, which will eventually stretch north and east into American Fork.

The Utah Transit Authority plans a FrontRunner station near UVU's (at)geneva locale, though UTA spokesman Remi Barron said the agency has no timetable yet for building it.

Work began this summer on two apartment complexes — Vineyard Crossing and ConcordGeneva — and a cluster of town homes called Edgewater with about 1,065 dwellings between them.

All are located at the southern end on land that housed the mill's administrative offices and saw minimal contamination through the years.

As Geneva goes from paper to bricks and mortar, Holdaway, Park, Fernandez and others expressed a desire to preserve elements of Vineyard's legacy.

The town recently formed a heritage committee. Two titanic, rusting foundry ladles kept from the Chinese salvage will be relocated near the 13-theater complex, now going up along Geneva Road between Orem's 400 North and 800 North. A mill locomotive and antique farm implements from some of Vineyard's original homesteads may be featured in Geneva's green spaces.

Holdaway wonders if these items won't soon be lonely relics of Vineyard's steel backbone and bucolic pastures.

"It's interesting that some people want to move here because of the open spaces," he said. "They don't realize that it isn't going to be open for too much longer."

tsemeradsltrib.com Twitter: Tony_Semerad