This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In 2007, the University of Utah began collecting umbilical cord blood donations for the National Cord Blood Stem Cell bank.

Two years later, it expanded, adding Utah's major labor wards to its public banking effort — giving more women in this most fertile of states the opportunity to save a life or contribute to research.

But public banks are tightly regulated and expensive. In 2010, the U. quietly suspended its program due to cost overruns and the departure of its founder, Linda Kelley, who moved on to work as chief scientific officer for one of the world's largest private cord blood banks, Cryo-Cell International Inc.

"It was a money loser," said Jo-Ann Reems, scientific officer of the U.'s Cell Therapy and Regeneration Program.

In the program's absence, obstetricians say, cord blood donations have declined.

Private banks have stepped up to fill the void, offering in marketing materials to process donations free of charge and ship them to public banks.

"It's a feel-good thing and not a moneymaker for us. But our view is none of these precious stem cells should be thrown out. They're just discarded as medical waste," said Eliott Spencer, co-owner and founder of the for-profit Utah Cord Bank in Sandy.

Nationally, private banks are loosely regulated, profit-driven and more prone to quality-control problems and aggressive marketing tactics, causing some medical authorities to question their role.

A recent Wall Street Journal analysis of government inspections found evidence of "dirty storage conditions" and "leaky" blood samples. The article cited researchers who say they often reject privately collected samples as unusable.

To cut costs and boost profits, some companies have begun outsourcing the processing and storage of samples without informing consumers. Fierce competition for customers is driving many to establish ties with research organizations and doctors.

"Parents are sometimes approached by doctors who are getting a kickback for sending consumers to private banks," said William Shearer, a professor of pediatrics and immunology at Baylor College of Medicine. "It's repulsive to me. Pregnancy is a high-anxiety time and patients are prone to making decisions they might not normally make."

—

'Science in the making' • Shearer is one of the authors assigned to update an American Academy of Pediatrics policy that discourages storing cord blood unless a sibling has a disease that could benefit from a transplant.

The new policy will diverge slightly and acknowledge the potential of emerging therapies without giving parents false hope, said Shearer.

Rich with stem cells — the body's building blocks for blood, organs and tissue — cord blood is used as an alternative to bone marrow transplants for treating cancer and other diseases of the blood along with some genetic and metabolic disorders. Research is also underway to see if stem cells can be used to treat spinal cord injuries, cerebral palsy, autism, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, heart disease and diabetes.

"But that's science in the making," said Shearer, noting the banking of cord blood for personal use is expensive and, for now, chances that it will be used are low — 1 in 2,700, by some estimates.

Private banks in the U.S. charge between $900 and $2,500 to process and cryogenically freeze cord blood, followed by annual payments to keep it stored.

Donating to a public bank, on the other hand, costs the donor nothing and is more likely to benefit someone who needs a transplant, Shearer said.

—

Value of options • Still, the argument for private storage can be compelling for expectant parents as insurance against future disease.

A child is less likely to reject his or her own cells than a donor's cells, and the chance of finding a perfect match at public banks is just 25 percent, according to Be The Match, a nonprofit bone marrow and cord blood registry in Minneapolis.

Fourteen-year-old Shannon Johnson of Syracuse was among the lucky ones.

Diagnosed with leukemia in February 2008 and requiring a stem cell transplant, she was unable to find a suitable bone marrow donor but found a cord blood match through the nonprofit.

The therapy worked. The busy, service-driven teen has been in remission for four years and will travel to Washington, D.C., next week to participate in a cord blood donation awareness event.

Her mom, Vickie Johnson, acknowledges it's "hard to say" whether she would have considered paying to privately store her kids' cord blood.

"I never thought my child would get cancer, not in a million years," she said. "But I definitely would have donated if I'd been given the option."

—

The challenge of donating • In Utah, however, donation options are limited.

"It's been a year since I've done a cord blood donation," said Jan Byrne, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the U. "When we had a cord bank, we had a very active collection service. It was easier. Nowadays it's kind of a pain."

Women who want to donate must use private companies, and it's up to them to research the company and order the collection kit, said Byrne. "We collect the cord blood [free of charge] and give it back to the family who is responsible for shipping it."

There's no national shortage of cord blood with about 195,000 units in the national public inventory, according to Be The Match.

But Michael Boo, the organization's chief strategy officer, said with 450,000 good quality units "we could increase the likelihood of providing a better match for virtually all Americans."

Boo would like to see more public collection sites open, but welcomes private banks as an alternative.

Of the 4 million births each year in America, private banks collect from about 5 percent to 6 percent, he said. "We don't see them as competition."

But, he acknowledges, there's more "variability" in the quality of private banks with "some very good banks and not-so-good banks."

—

Capturing Utah's cord blood • In five years, the number of successful cord blood transplants nationally has tripled, a trend that's likely to continue as new medical applications surface and private banks surge to meet demand.

Spencer welcomes scrutiny of the booming, multibillion-dollar global industry by regulators and consumers.

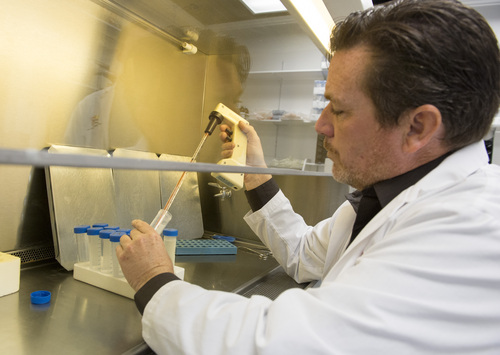

"There's a lot going on and it seems to have escalated in recent months," said Spencer, who started Utah Cord Bank nine years ago. "The first cord blood we processed as my son's. We started doing it because we thought methods being used were too expensive and not as good as they could be."

The for-profit company is not accredited by the American Association of Blood Banks (AABB), which sets industry standards, but Spencer said federal inspectors have visited its facilities three times and haven't had concerns.

It has survived as a price leader and by carving out a niche as "the lab's lab," processing and storing samples for its large, international competitors, he said. Spencer has learned over time which companies to avoid.

"Some brokers will collect lifetime storage fees from clients, but won't pass that onto the lab that does the storage. Then if they go out of business, that leaves us with unfunded samples," he said, noting his bank stores them anyway.

Few of the thousands of samples that Utah Cord Bank stores came from Utah, which has yet to join 27 states with laws requiring doctors to inform patients of their cord blood options.

To remedy this, his company pays obstetricians a $200 "compliance fee" for informing patients about cord blood storage and donation options "in a balanced way."

Attorneys assured Spencer the strategy doesn't run afoul of federal anti-kickback laws. "They have to earn it by educating their patients and performing the blood collection," he said.

To tackle objections over cost, Utah Cord Bank also offers to put a portion of its upfront fee into a college fund for consumers to tap once their babies come of age.

"Our goal is to make this affordable and capture as many units as possible," said Spencer, "whether to serve the public good or serve the family who needs it to save their child."

Twitter: @KStewart4Trib —

Treating disease with stem cells

Cell therapy

Cell therapies involve transplanting human cells to replace or repair damaged or diseased blood, tissue or organs. Bone marrow transplants of hematopoietic (blood-forming) stem cells are the most common.

How does it work?

Hematopoietic stem cells can form mature blood cells, such as red blood cells (which carry oxygen), platelets (to stop bleeding) and white blood cells (to fight infection). In addition to treating cancer and other blood diseases, they are being tested for use with autoimmune, genetic and a host of other disorders.

Why cord blood?

There are three sources of hematopoietic stem cells: bone marrow, peripheral blood donation and umbilical cords. Cord blood is a valuable alternative for patients in urgent need of a transplant because samples are banked, blood-typed and easily searchable, and there's evidence that they are less prone to rejection from the host.

How to choose a private cord blood bank

• Talk to your doctor about options early in your pregnancy.

• The American Association of Blood Banks and many doctors urge parents to use accredited banks.

• Find out if your bank operates in a state that licenses them (California, Maryland, New Jersey and New York).

• Ask about storage methods, viability of blood samples compared with other banks and financial stability.

Other questions to ask:

• What tests does the lab perform on maternal blood, for infectious disease markers and contamination?

• Does the lab have a quarantine tank for samples that might transmit disease?

• Does the lab inform parents, before storage, if the collection is too small for transplant and give them an option to not store it?

• Does the lab offer a refund if the collection has problems?

• What is the geographic location of the storage site (is it vulnerable to hurricanes or earthquakes)?

• What types of security and backup power systems are in place?

• Are samples processed within a certain time frame and how are they shipped?

Sources: Parent's Guide to Cord Blood Foundation and American Association of Blood Banks