This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

There's a small concern lurking beneath the surface in Utah's same-sex marriage case, a quiet question that some experts say could derail the state's push to permanently ban gay and lesbian unions.

Although few believe it poses a serious threat to the case's trajectory — likely headed to the U.S. Supreme Court by summer — the question persists:

Could Kitchen v. Herbert be thrown out on a technicality?

On Tuesday, Utah's lead counsel Gene C. Schaerr drew attention to a question posed to both sides by a three-judge panel at the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals last week regarding whether the lawsuit targeted the appropriate state and county officials.

The technical term is Article III standing. What it means is according to constitutional standards the court must consider, "at an irreducible minimum" the party seeking to sue must have suffered injury that can be traced to the action of the defendant in the case.

In the Utah lawsuit, the three couple plaintiffs represented by Peggy A. Tomsic and James E. Magleby named the governor, the attorney general and the Salt Lake County clerk in the case.

They allege these three officials are responsible for same-sex couples being denied marriage licenses and for out-of-state marriages remaining unrecognized in Utah.

Schaerr's letter insists this belief is accurate.

Why would Utah's lead attorney be volunteering to the court that the governor and attorney general are, in fact, the proper people to sue?

If the court finds that they're not, the appellate judges may decline to rule in the case, leaving Judge Robert J. Shelby's ruling to stand as law in Utah.

That's what happened with California's Proposition 8 and the lawsuit Hollingsworth v. Perry that took the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court — after hearing the case, five out of nine justices voted to dismiss the appeal for its lack of jurisdiction, thereby leaving the decision of the lower district court to stand.

"It's the kind of legal technicality that could screw up the case," said Carl Tobias, judicial appointment expert and professor at the University of Richmond School of Law. "There's always a possibility, but courts tend to be reluctant to base a decision entirely on jurisdictional issues when it's a case like this. I think they're reluctant. It sounds like these judges want to get to the merits."

During Utah's arguments last week, Judge Jerome A. Holmes — widely considered to be the "vote to get" in the case — asked Tomsic to explain why the defendants her plaintiffs had singled out were appropriate.

Further, he asked whether the state continued to have the right to appeal the case, given that Salt Lake County Clerk Sherrie Swensen declined to appeal Judge Shelby's Dec. 20 decision to overturn Utah's same-sex marriage ban.

"You sued the clerk of court," Holmes said, referring to Swensen. "But the clerk of court is not on the appeal, and, it would seem to me that creates a fundamental basis for concern about where jurisdiction lies in this case. "

Tomsic argued that because the governor and the attorney general have authority over the county clerks in Utah — unlike in other states where clerks who issue marriage licenses are members of the judicial branch of government — they are, ultimately, the proper authorities.

Immediately after Shelby overturned Utah's marriage amendment, county clerks were inundated with requests for marriage licenses from gay and lesbian couples.

Some, like Salt Lake County, began issuing them without hesitation. Others took days to begin handing out marriage licenses to all couples — regardless of their gender.

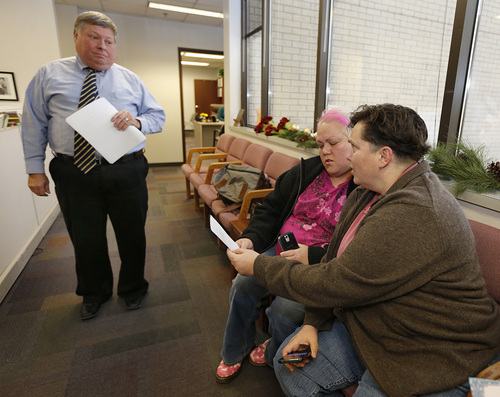

Utah County's clerk, Bryan Thompson, took nearly a week to begin issuing licenses, prompting threats of a lawsuit from a lesbian couple who had been previously denied.

The explanation several Utah county clerks gave was they were waiting on direction from the attorney general or governor's office as to how they should handle the situation.

This, Schaerr states in his letter to the court, is further proof that with or without the Salt Lake County clerk, the governor and the attorney general are within their jurisdiction to appeal the case to the 10th Circuit and, perhaps, beyond.

"Utah marriage licenses are issued by county clerks [...] not by court clerks," Schaerr wrote. "Plaintiffs' suit thus satisfied the demands of Article III standing."

The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals panel, consisting of Judges Carlos F. Lucero, Paul J. Kelly and Holmes, will likely address the question of jurisdiction in their decision.

It is not known when this decision may be issued, though experts estimate it could take anywhere from one to three months.

Should the court rule on the merits of the case and side with — or oppose —the lower court's decision, its ruling would effectually extend to all states in the 10th Circuit, including Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah and Wyoming.

Twitter: @Marissa_Jae