This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Andrea Griggs was grateful to hear the words, "Your child has autism."

"We were relieved to finally have the answers we had been seeking for so long. We were relieved to finally know what we needed to do to help Jaxon achieve his potential," said the Murray mother of four.

But a diagnosis of autism, the Griggses soon learned, is a double-edged sword that can be used by health insurers to sever medical benefits, which can be financially devastating for families. To pay for the expensive Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy Jaxon needed, the Griggses had to sell their home.

"It's a decision no family should have to make," Griggs said. "But we're lucky, really. There are plenty of families who lose everything and still can't afford treatment for their kids."

Utah is one of 16 states that don't require insurers to cover autism treatment — despite repeated attempts at insurance reform. Sen. Brian Shiozawa, R-Cottonwood Heights, is giving it a third try this year with SB57, which is scheduled for its first public hearing Friday in the Senate Business and Labor Committee.

His bill competes with a $2 million measure to continue Utah's autism "lottery," a program created in lieu of an insurance mandate. Fewer than 400 families have gained ABA therapy through the initiative, funded through Medicaid, the state's public employee insurance plan and privately funded grants.

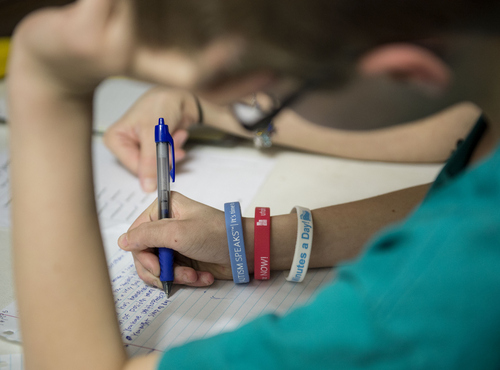

By all measures the program has been a success for the enrolled children. Testing before and after one year of treatment shows across-the-board academic and behavioral improvement. And the cost to insurers was less than anticipated.

"It showed what we thought it would," said Shiozawa, who wants to extend ABA's proven benefits to more privately insured Utahns.

"Some lawmakers want to let the [lottery] play out. We agreed to do that last year and we withdrew my bill. But that can no longer be used as an excuse," Shiozawa said. "The results are in. Here's an evidenced-based therapy that works and we have a vulnerable population that needs help."

Utah's autism rate of 1 in 47 children is believed to be among the nation's highest. The advocacy group Autism Speaks estimates 18,000 Utah children live with the disorder.

SB57 would require state-regulated health plans to cover up to $36,000 worth of ABA therapy a year for children through age 8, then up to $18,000 a year through age 17. It mirrors the coverage that Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams proposed for county employees in his 2014 budget.

Small businesses with fewer than 50 employees would be exempt from the mandate if they could show it raised the cost of their health benefits by 2.5 percent or more.

Studies in states that have imposed mandates have seen no significant bump in insurance premiums.

But the cost of treatment is too much for some families to shoulder alone.

The Griggses pinched pennies and tapped their savings to pay for Jaxon's ABA treatment, which was $25,000 for the first year. They also faced $42,000 in medical bills that accrued from his stay 3½ years ago at the University of Utah's neuropsychiatric unit. It was that stay that led to his diagnosis.

The Griggses had long thought Jaxon was on the autism spectrum but they couldn't find a health professional capable of making the diagnosis.

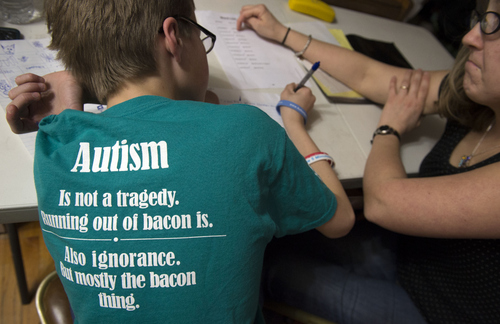

Jaxon, now 12, is on par academically with his peers but socially and emotionally impaired, explained Griggs.

"So it wasn't until he was about 7 that he started to notice he was different," Griggs said. "He didn't know how to be OK with other kids or how to relate to them and it depressed him."

It reached a crisis in 2010 one day on the playground. "He was jumping off the top of a slide. The recess aide asked him to stop and when asked to explain why he wouldn't, he said, 'I've figured out the math and figured out if I land just right, I'll break my neck and die,' " recalls Griggs.

Doctors at the U. wouldn't release Jaxon from the hospital until his family secured an ABA therapist and regular psychotherapy.

"My husband is an accountant, and we sat down and crunched the numbers and realized the only way we could get treatment for our older son was to sell our home," Griggs said. "So we prepared to say goodbye to our friends and neighbors and to leave the only school my kids had ever known. It wasn't easy but there was really no question for us."

Shortly after Jaxon was diagnosed, the Griggses' second son, Ender, was also diagnosed with autism. ABA "worked miracles" for both, said Griggs.

"Before ABA, Jaxon was missing 10 to 15 days of school a year because of the emotional toll it took on him. I was bringing him to the doctor all the time because he complained his stomach or heart hurt; the stress was manifested physically," she said.

"Today he's attending school and getting better grades. ... We feel like if he wants to, he'll be able to go to college, get married and have kids. That's huge for us."

Griggs said other Utah children deserve the same chance.

"I know you can't compare autism to cancer, that cancer is different," she said. "But you would never tell a child with cancer, 'We have a treatment for you, but sorry it's not covered and you can't afford it.' We don't tell those parents, 'Take your child home and watch them regress.' "