This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Amber Christensen spent Valentine's Day 2009 watching, again and again, a scene from her husband's death.

She would rather you don't Google the video, but here's what it shows:

At roughly 50-below zero, Federico Campanini is on all fours, tethered to exhausted mountain rescuers by a rope around his neck. They tug the makeshift leash, barking in Spanish: "Come on! Come on!"

Their only hope is to coax the Argentine guide and onetime Salt Lake City resident up to Aconcagua's 22,837-foot summit — from which he set off two days earlier on Jan. 6 — and back onto its easiest route.

But that's a few hundred yards away, and "El Fede," as he was known to friends and loved ones, can barely crawl for 10.

Over the radio, a rescuer asks permission to leave him for dead. The request is denied.

It sounds like the cameraman begins to cry.

—

Fede's final days • Campanini died of pulmonary edema a few hours later, with rescuers still by his side.

The video sparked a media firestorm in Argentina. Some had questioned Campanini's state of mind for leading his four Italian clients astray, and now others — including Campanini's father, Carlos — criticized rescuers for perceived callousness and a lack of preparation.

But as Christensen replayed it some 30 times, she realized the blame game was doing no good. The rescuers had tried their best, as had Campanini.

"I just don't want this to ever happen again to someone, for a family to go through losing someone," she says. "This did not have to happen. I did not have to become a widow at 33."

Each year, thousands try to summit Aconcagua — the tallest mountain in both the Southern and Western Hemispheres — and many years, some die.

It's thought that Campanini became disoriented on the summit when his GPS malfunctioned during a swift-moving storm. He then spent his remaining energy retrieving a client who fell into a crevasse, and when rescuers reached the group two days later, Campanini was still breathing but far gone, his face blackened by frostbite.

Longtime Aconcagua guide Gabriel Barral says he's still trying to understand why his best friend with the famous smile is no more.

"It's hard to believe that this happened to him, because he was very focused on safety," Barral says. "No pushing to the limits when you are with clients."

Previously, Campanini had gotten lost in a storm guiding on Washington's Mount Rainier, and rather than wander farther off course, he simply radioed and waited for help.

But Christensen believes that faith was misguided on Aconcagua because of three factors: 1. It took too long to coordinate the rescue, 2. A spotter in a helicopter flyover wasn't familiar with that side of the mountain, and 3. When rescuers arrived, they didn't have what they needed to save her husband.

—

A new purpose • In Salt Lake City, Christensen alternated between despair and denial as she read conflicting media reports. Eventually, a call from Campanini's sister woke her at 3 a.m. on Jan. 9.

"The only word she said was 'Confirmado,'" says Christensen, who threw the phone, screamed and collapsed.

"She was quite beside herself, and she still is, four years after his death," says her father, Todd Christensen.

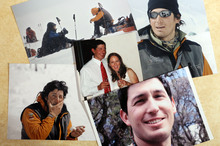

They fell in love on Aconcagua in 2002 — her a wide-eyed traveler and the sturdy, olive-skinned Fede her enchanting guide, singing in Spanish as they walked and pointing out the constellations at night. "He was just a beautiful man," she says. She stayed in Argentina for three years before they married and moved together to Salt Lake.

Barral says that when a smitten Campanini introduced him to Christensen, he thought, "'Well this is a good girl for Fede.' She had a big heart. She was sensitive."

Christensen spent three weeks back on Aconcagua arranging Fede's cremation — first waiting for workers to retrieve the body amid a flurry of emergencies, then for his body to thaw. She would look up at the summit from base camp, knowing that Fede was now both close and impossibly far.

"I met people that I hadn't met before that knew him, and they told me things that he said about me and our life," she says. "It was this tragic, beautiful sort of goodbye."

She soon discovered that as a widow she was in a unique position to do attract support, so she launched the "El Fede" Campanini Foundation in July 2009. In January 2010, mountain workers helped her install three rescue caches with sleds, splinter kits, oxygen, medicine, ropes and other necessities. (Each has a combination lock, with a code available by radio.)

Remote Medical International executive Tom Milne, who once guided on Aconcagua, says the peak is particularly dangerous because of its reputation as "nontechnical," meaning any strong hiker can conceivably reach the top. While that's true, many visitors don't have experience at high altitudes, and some exhibit haphazard and boorish behavior in pursuit of one of the vaunted Seven Summits.

Rescues are frequent, and Christensen's idea "is an incredibly simple and effective solution," he says. "It's just what the doctor ordered."

—

"Bittersweet" • The effect of the caches was truly immediate. Just an hour after workers installed the highest cache, they used supplies to aid a woman who collapsed on the summit.

Other testimonials for Christensen's caches include:

• Erik Endert, a mountain guide for Rainier Mountaineering Inc. (for whom Campanini worked), told Christensen that he had a "got-to-keep-it-together" moment when he was nursing a sick client at high camp and saw an "El Fede" sticker on the oxygen bottle. His client made it down, saw a doctor and returned for a successful summit attempt the next year.

• This January, Argentine porter Matias Cruz helped rescue a Japanese climber at 20,000 feet. Thanks to one of the sleds, "it was a smooth descent to base camp," he wrote. He believes the caches have saved multiple lives, and adds "It is amazing to see how successful rescues can be when the correct material is available."

"Amber's story is pretty intense, and I give her a huge high-five for seeing this through," Milne says. "It's too bad that this is what it took to get something done."

Christensen repeatedly uses the word "bittersweet" to describe the success of her foundation. It gave her a connection to her late husband and a sorely needed purpose, but it's also a constant reminder that, "he shouldn't have died. If he had had any one of these things, he would have survived."

Christensen says the government, which charges foreigners upward of $800 to summit Aconcagua, has reneged on its pledge to replenish the caches, so she returned with another load of supplies earlier this month. She's keeping a blog about her time on the mountain and also plans to self-publish a book about her life with Campanini.

She speaks about her foundation in an almost pleading tone. She doesn't want to keep flying back to Aconcagua and reopening that wound. She, and others concerned about her well-being, are hoping that somebody else will someday take over the heavy lifting.

"She just can't quite let him go," says her father. "I kind of think that it's almost an anchor. But on the other hand, I'm really proud of what she's trying to do."

Twitter: @matthew_piper —

Contributors to rescue caches

SkedCo donated Skeds (rescue sleds) and splinter kits (to mobilize people with injured limbs). Remote Medical International gave two oxygen tanks and provided discounts on supplies. Rainier Mountaineering Inc. gives $500 each year. Petzl pitched in three ropes. Caches also contain survival blankets, first aid kits and other necessities. Donations are welcome at http://elfede.org. —

Pico El Fede

Gabriel Barral met his best friend in March 2000 in Mendoza, Argentina, as both were testing in a mountain guiding program.

Federico Campanini had been head of the class on the written portion of the test, and then Barral — a former competitive runner — found himself well behind "El Fede" throughout the physical exam.

"And I was in my best shape," he says. "I said, 'Who is this guy that I cannot follow?'"

The two became fast friends. In 2004 they teamed up for a "life-changing" climb in the Quebrada de la Jaula ("Broken Cage") section of the Mendozan Andes. A fox ate most of their food on Day Two of the expedition, and they wound up losing 15 pounds over the next week, but they completed an ascent that had only been done a few times before.

After Fede died, Barral thought of that experience. They had long talked about going back to the area and tackling a so-called virgin peak — one that had never been summited.

So in October 2009, Barral and some friends of Campanini — or people who Barral thought Campanini would have liked — decided to do just that, to honor El Fede.

But there was a problem. In a bizarre twist of fate, some locals had already had that idea.

Just days earlier, a group that included a porter from Campanini's rescue climbed the peak that Barral and his group were targeting.

At the last minute, Barral and Co. decided to climb another virgin peak, a mere 300 yards or so away.

"It was amazing," Barral says. "Two teams summiting the mountain, thinking of him."

They called it "El Fede's Peak," and the porter's group dubbed theirs "Campanini Peak."