This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Jean de Dieu Rukundo is one of the lucky ones.

Nineteen years ago on Sunday, the then-7-year-old Rukundo huddled with other Tutsi children and women in a church they hoped would be a refuge against armed Hutu militia. By then, tens of thousands of Tutsi had already died in Rwanda in what would be a 100-day siege against the minority ethnic community that would leave up to one million dead.

Rukundo said he and others escaped only after the attackers ran out of ammunition, fleeing to the border with Burundi, where many more were killed by Hutu militia.

Rukundo, who now lives in Taylorsville, spoke to The Salt Lake Tribune during a commemoration of the 1994 Rwandan genocide held at the Wagner Jewish Community Center in Salt Lake City.

The Never Again Association, a new Utah group aimed at raising public awareness of genocide and providing support to victims, hosted the gathering. Co-founder Zeze Rwasama said about 50 survivors have relocated to Utah over the past four years through the diversity visa — or green card lottery.

"Now, within the umbrella organization, when someone comes we contribute money to have an apartment for them, food for them and help them to find jobs as well," said Rwasama, who came to Utah as a refugee in 2001.

Consolee Nishimwe told the audience of about 100 that it was "not an easy thing" to share her story. She was 14 when the attacks began, triggered when a plane carrying the country's president was shot down while arriving at the Kigali airport on April 6, 1994.

Nishimwe was the oldest of five children of two school teachers. She recounted the days her family spent "having to hide just because of who you are." Only Nishimwe, her mother and one sister survived the massacre as Hutus, many wielding machetes, turned on their Tutsi neighbors.

"It was hard to hear people walking around talking about how they killed my brothers," Nishimwe said.

While her life was spared, Nishimwe was raped and later learned she'd been infected with the HIV virus in the attack.

Nishimwe, who wrote a book about her experience titled "Tested to the Limit: A Genocide Survivor's Story of Pain, Resilience and Hope," now lives in New York and advocates for other survivors.

No matter what horrible circumstances life presents, never lose hope, she told the audience.

Jacqueline Murakatete, who was 9-years-old then, said she is still haunted by the memories of seeing family and friends killed. Now an internationally recognized human rights activist, Muraketete said many other survivors are still struggling to get by on a daily basis, let alone rebuild their lives. Murakatete and other speakers noted the United States and the rest of the international community reacted to the slaughter only after it was over.

"These challenges deserve more attention," said Murakatete, a moving force behind the effort to create a trust fund for survivors that will be launched later this month.

Mathilde Mukantabana, the newly named Rwandan ambassador to the U.S. and also a survivor, said efforts to remember the genocide and address needs of survivors is hampered by a "trend of denial" similar to attempts to minimize the Jewish Holocaust.

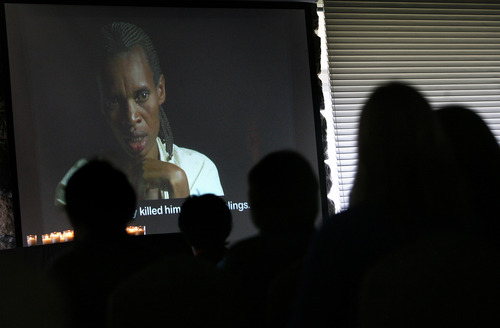

The event also featured an excerpt from "Voices of Rwanda," a video archive of testimonies created by documentary filmmaker Taylor Krauss.

Rukundo — who lost three brothers, a grandfather and grandmother and many other relatives in the genocide — came to Utah in 2011 on a diversity visa. He said he is seeking an engineering degree and doing what he can to support "those people who do not have somebody who can take care of them."

brooke@sltrib

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib