This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Wet skies have brought relief to allergy sufferers, but don't expect it to last, say experts who predict earlier and longer allergy seasons to be the new norm.

One possible culprit: climate change.

Putting aside the debate over what causes global warming, "everyone agrees carbon dioxide levels are on the rise," said Rafael Firszt, an allergist at the University of Utah. "Carbon dioxide generally makes plants bigger, and bigger plants produce more pollen."

Warming temperatures can also prolong the flowering season, research shows.

"We are experiencing longer allergy seasons, earlier onset and there is just more pollen in the air," said Richard Weber, an allergist at National Jewish Health in Denver, and president of the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

What this means for sniffle- and sneeze-prone Utahns, though, is hard to say.

"Predicting the allergy season is a crapshoot, a little like predicting the weather six months from now," said Duane Harris, an allergist at Intermountain Allergy & Asthma, which measures and publishes Utah's official pollen count.

So far, this year is looking a lot like last year.

"For three years running, we've had wet, cool springs. If that persists, the pollens will come a little later than usual," Harris said. "The first tree we see is elm, sometimes as early as mid-February. This year we didn't see it until the second week of March."

Complicating local pollen forecasts are factors beyond temperature and carbon dioxide, such as pollution, moisture and sunshine, or UV radiation.

"It's complicated," said Weber, noting that conditions for a healthy grass pollen season aren't necessarily favorable for trees.

"Last year in Denver, we had a horrendous tree season. Everything was pollinating at the same time, some trees later than usual and others earlier than usual," he said. "But this March, not so much. So why the difference? I think it's mostly due to it being a dry winter. ... Tree pollen is very dependent on the kind of rainfall that happens in late fall and winter, because trees store up the moisture."

Grasses, on the other hand, tend to thrive in wet springs, Weber said.

Bad air plays a dual role as pollutants interact with greenhouse gases and irritate nasal passages, making people more susceptible to allergies, Weber said. "A study in Los Angeles, California, found people who live along heavy traffic routes had higher rates of being allergic."

Utah's winter inversions, though, are short-lived and don't coincide with spring blooms, he noted.

Still, how the changing climate is affecting allergies is of increasing interest to scientists. Weber published a survey of the growing body of literature last spring in the Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology.

A 2002 study done in Great Britain, for example, found 385 plant species that are flowering earlier, advancing by 4.5 days over the past decade. And 30 years of European pollen monitoring has shown increases in hazel, birch and grass counts in Switzerland and Denmark, the article says.

Researchers in Mediterranean areas have traced higher oak and olive pollen counts, notes Weber. And data from a dozen sites in the midwestern United States and southern Canada show the ragweed season has been extended by 13 to 27 days, he said. Short ragweed pollen particles have grown in size and production between 61 percent and 90 percent.

More research is needed, Weber said, to tease apart the complexities, especially in the U.S., which hasn't been monitoring pollen for as long as European countries have.

Until then, he advises patients to investigate what triggers their allergies and, to the degree possible, anticipate pollen blooms.

"It's much better, when treating your allergies, to start taking medication before it's really bad," he explained. "If you know you're allergic to grasses, for example, start taking your medicines in the beginning of May." —

Harnessing hay fever

What is pollen?

Pollen, made up of microscopic powder granules, is the male fertilizing agent in plants. Grasses, trees and weeds, which are pollinated by the wind, are the main culprits for causing allergies.

Controlling allergies

There is no cure for allergies, but health officials recommend the following steps to control or reduce symptoms:

Keep outdoor activities to a minimum when pollen counts are high. Most pollen is released at midday, between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m.

Keep windows to your car and home closed; use air-conditioning.

Do not air-dry clothes or towels outside.

Take medication early; it's easier to prevent symptoms than it is to alleviate them.

How to track pollen blooms

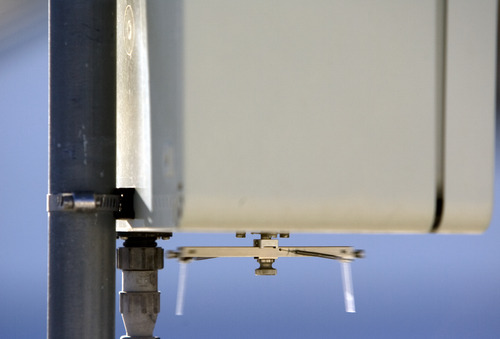

Utah's official pollen count is updated daily by Intermountain Allergy and Asthma Clinic at: http://bit.ly/chs8ov.

Pollens are reported as low, moderate or high as compared with normal pollen levels for Utah. Take precaution when pollens that you are allergic to are shown to be moderate or high.

Source: Utah Department of Health Asthma Program