This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Christina Harms died a prisoner in her own home.

The disabled 22-year-old was routinely tied to a bar inside a dark closet and bound by zip ties. Her arms were bandaged, her body bruised. Every motion was controlled by an alarm system and a knife rigged to the door. Cardboard placed beneath her was covered in human feces. Her only company, a sketch of Jesus Christ.

Two years later, friends of Harms appeared in a 3rd District Courtroom on Friday. They begged a judge to sentence Cassandra Marie Shepard, one of Harms' tormentors, to the same fate: spending the rest of her life locked away in small, cramped cell — hidden from the world.

The judge agreed.

"I don't think there will ever be understanding. There will probably never be closure," said Judge Katie Bernards-Goodman before handing down Shepard's sentence. "But today is a day for justice."

Shepard, 29, was sentenced to spend between five years and the rest of her life in prison on charges of first-degree felony aggravated abuse of a vulnerable adult and second-degree felony manslaughter — reduced charges to which Shepard pleaded guilty in a deal with prosecutors. A sentencing commission will determine how long she ultimately will be in Utah State Prison.

But for Marilee Nelson and Tonya Willprecht, family friends of Harms from Minnesota, the sentence was not enough.

"I wanted to look that woman in the face and tell her, 'May God forgive you, because I never will,' " Willprecht said outside the courtroom. "She needs to be treated the way Nina was treated. That would be fair. That would be justice."

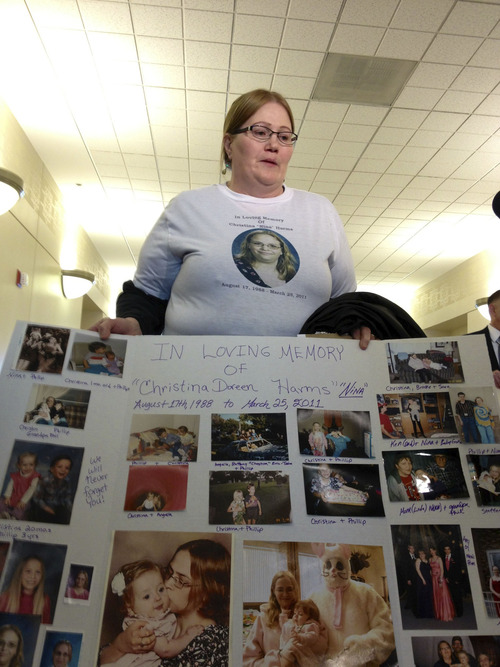

Standing beside a cardboard display covered by photographs of Harms and her young daughter, each woman addressed the court in turn.

Each said they had offered to care for Harms before Shepard moved from Aberdeen, S.D., to Utah in 2010, but Shepard refused.

"[Harms] had dreams — she wanted to go to college, have a family," Nelson said, standing before the court wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with Harms's smiling face. "We would go to see her every couple of months, but then one day, she disappeared."

After Shepard and Harms moved to Utah in May 2010, the women lost all contact.

They were worried, Nelson said, but didn't know where to turn. Shepard was the cousin and legal guardian of Harms, who had fetal alcohol syndrome and the mental capacity of a teenage girl.

The next time they heard anything about Harms was after her death on March 25, 2011.

On that day, police were called to a possible overdose at a Kearns home in the 4900 South block of 5415 West and found Harms unconscious, according to the Unified Police Department. She was later pronounced dead.

At her funeral, the casket was closed. Friends and family could not look upon the face they said "lit up any room" because Harms was battered too severely.

Prosecutors said the adults in the home — Shepard and her mother, Sherrie Lynn Beckering, and stepfather, Dale Robert Beckering — had abused Harms severely and often.

An autopsy showed Harms was extremely dehydrated and had potentially fatal levels of Benadryl or a similar drug in her system.

A jury in September found Sherrie Lynn Beckering guilty of first-degree felony aggravated abuse of a disabled adult. In January, a judge sentenced the 51-year-old woman to five years to life in prison for her role in Harms' death. In February 2012, a jury convicted Dale Beckering, 54, of abuse of a vulnerable adult. He is serving up to 15 years in prison.

Shepard was originally charged with murder and aggravated abuse of a disabled adult, both first-degree felonies punishable by life in prison. The plea deal allowed Shepard to avoid two life sentences.

Twitter: marissa_jae