This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Dylan Thurgood constantly had hands on the brain.

No, he wasn't thinking about hands. Instead, the 10-year-old literally had his glove-covered hands all over a gray, moist and slightly squishy brain.

"It's mushy and sort of foamy," the blond boy from Magna said. "Maybe about five pounds?"

Next to the one he held was another brain. And then another. Three-and-a-half brains in all — along with a wet spinal cord. Judd Cahoon, a University of Utah medical student, held up a half-brain and, with a metal pointer, mapped it all out for the small crowd gathered at the table inside The Leonardo in downtown Salt Lake City on Saturday.

The cerebrum. The cerebellum. The protective dura mater— which translated from Latin means "tough mother."

It was part of the University of Utah's Brain Institute and the Interdepartmental Program in Neuroscience's Brain Awareness Day at The Leonardo. For the past week, about 80 neuroscientists and volunteers traveled around to Salt Lake Valley schools, educating students on how the brain works, the effects of concussions and avoiding drugs or alcohol.

Some of those who came to The Leonardo got to try on goggles that simulated what the world looks like after a concussion. Another set of goggles simulated being just below the legal blood-alcohol limit for driving, and a final set of goggles showed what it looked like at more than twice the legal limit.

Matt Diamond, 30, put on the goggles simulating the higher blood-alcohol level and tried to walk a straight line taped to the floor. He staggered, carefully placing one foot in front of the other and almost knocked over 7-year-old Landon Herlocker.

"It's like crazy double vision," Diamond said laughing. "It's terrible."

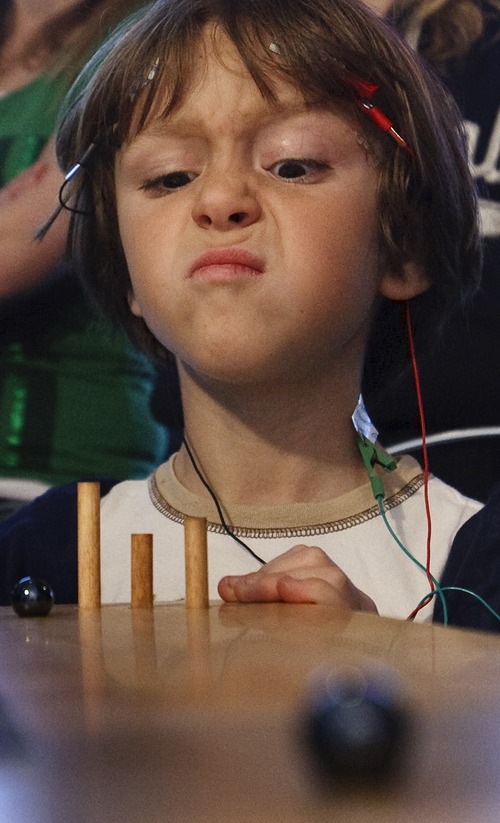

One of the most intriguing attractions was the mind-control exercise — a literal example of mind over matter.

Four people sat at corners of a table with a metal ball in the middle. With electrodes attached to their foreheads and necks, the trick was to relax brain activity and draw the metal ball toward your corner without the benefit of using hands.

Scott Hiatt, an electrical engineer who ran the challenge, said the electrodes measured alpha, beta and theta brainwaves. The activities of those waves were visible by watching small pegs — each marked by the corresponding Greek alphabet letter — in front of each person that rose and fell throughout the exercise.

Hiatt said the goal was to keep the beta peg high and the alpha and theta pegs low.

Easier said than thought.

"I was getting frustrated as the ball moved away," said Russell Culley, 36, of South Jordan. "And then instead of relaxing, I was thinking about being frustrated."

Hiatt said the work in using brain waves to control movement is a critical area of science that is being studied to help people who are paralyzed or missing limbs control the movement of robotic arms.

There have been recent advances in that area of neuroscience, including reports last year in the scientific journal Nature of a quadriplegic woman who raised a cup of coffee to her mouth by using brainwave control.

Carly Spackman, an 11-year-old in a pink shirt who came with her parents from Richmond, said the brain-wave exercise was both "frustrating and cool." So were the actual brains nearby — though she doesn't expect those to be the last brains she ever sees; she wants to be a neurosurgeon when she grows up.

"It's all she's wanted to be for as long as we can remember," her dad, Kelcey Spackman, said.

In other words, she's got brains on the brain.

dmontero@sltrib.comTwitter: @davemontero