This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Investigators were confident the touch DNA they brought to Utah's crime lab a couple years ago would confirm they had the right suspect. But an analysis pointed to someone else, according to lab director Jay Henry.

In fact, the lab clears about a third of the people initially suspected of a crime, Henry said. But funding constraints have reduced the lab staff over the past few years, creating long delays in the kind of analysis that cleared the innocent man. Now the lab is asking legislators for two more DNA analysts to handle the mounting evidence and help mend a lab still limping from a "brain drain" it has experienced for years.

Low wages and state budget cuts have cost the lab about half its staff since 2005, including two computer forensics specialists and its only firearms and toolmarks expert, creating a backlog of cases in a lab that now processes about 10,000 pieces of evidence every year. Ideally, the lab would turn an analysis report in three weeks. But the average completion time has tripled for crimes that don't have the priority of a violent felony. Too much lag time in getting lab results can result in valuable evidence being excluded from trials or force judges to delay them.

—

Making progress • In 2005, state forensic scientists earned starting salaries of $28,000 a year, or about $13.55 an hour, making them the lowest-paid in the country. Some left for better-paying jobs out of state or in the private sector. By 2006, the Utah Department of Human Resources Management (UDHRM) estimated that salaries for Utah's forensic scientists were 28 percent below average for the western United States.

As staffers left, the work load kept piling up until it nearly doubled.

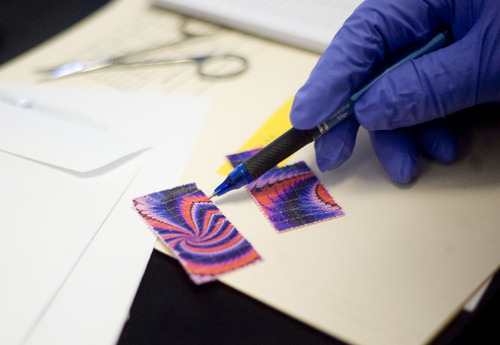

DNA can now be identified from hair samples, or from a surface that was merely touched. The lab can discern DNA profiles from ever smaller amounts of blood: Several years ago, the lab needed a drop of blood at least the size of a dime. Now the same evidence can be extracted from a speck the size of a pinhead. But these advances mean there's twice as much evidence, even though the number of new cases has remained fairly stable at about 15 to 20 per week.

"We've been victims of our success," said Henry.

A decision on new hires for the lab likely won't come until later in the session, but Henry is hopeful. The lab has been slowly rebuilding its team, improving retention with better pay, and this year the state may approve funding for a new facility.

In the past two years, lawmakers have given the lab the money it needed to pay veterans staffers proportionately more than people with half their experience. Now the average pay is about $24 an hour, which a National Compensation Association of State Governments report pegs at about 10.5 percent below average for the Mountain West public sector, according to the UDHRM.

Henry also has been able to replace the firearms and toolmarks expert, and in July, the Legislature gave the lab two chemists to keep up with Utah's newest concern: spice and bath salts.

"That's really been a barn burner for us the past couple years. It wasn't even an issue in 2010, but just a terrible issue in 2011 and 2012," Henry said.

Lawmakers are seeing a return on that investment: In November, they proposed adding new analogs for spice and bath salts — new combinations of legal compounds to produce the same dangerous result, identified by the lab's new hires — to the controlled substance list. Lawmakers intend to vote on adding even more analogs later this session.

—

New lab is needed • While delays in processing evidence can be frustrating for prosecutors, Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill said he understands that the lab serves the entire state — that's 140 agencies — with historically scarce resources.

"I can empathize with [Henry], what his challenges are. Sometimes they can get burdened, but they have never lost their professionalism," Gill said. "They have always done more for the dollars invested in them. The return on investment from the taxpayer has always been good."

But that investment must continue, he added. Under-funding the lab is like giving a law officer a gun but not paying for the bullets, Gill said.

In the future, the lab wants to hire two new computer forensics specialists to replace the pair lost to budget cuts in 2008. Hard drives once measured in gigabytes now store terabytes, and it's taking longer to keep up with the mounting data, Henry said.

Henry also has his sights set on a new $35.6 million lab — not just for his team, but to house the medical examiner's office and the Utah Department of Agriculture labs. The crime lab lacks space for ballistics testing, which has to be done off-site, the chemical storage room is too small, there's no dedicated training and conference space, and its information technology is dated. If a fire ever broke out, the sprinkler system would damage its expensive equipment; a new fire suppression system wouldn't.

On Feb. 5, Department of Public Safety Commissioner Lance Davenport pitched the new lab to the legislature's Infrastructure and General Government Appropriations Subcommittee. Funding for the lab is a priority in Gov. Gary Herbert's recommended budget for 2014.

"It's been a top priority for [the departments that would use it] for five or six years," Davenport said.

Twitter: @mikeypanda