This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In another era, Kellie Madsen might have worn a ring of jangling iron keys.

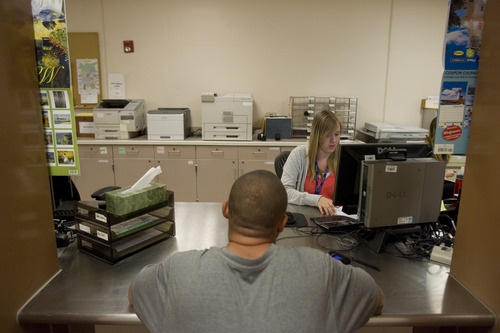

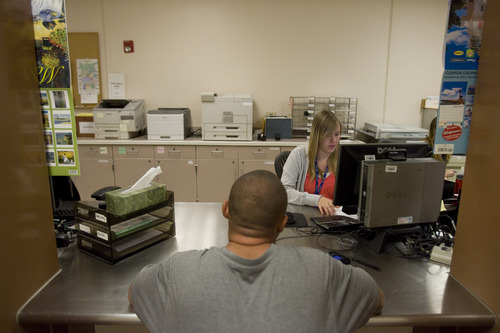

These days, her tools are a computer and a telephone, but the effect is the same: Madsen, a screener for Salt Lake County's pretrial-release program, can set people free from the county jail.

County officials say the pretrial-release program is essential for relieving jail overcrowding and treating fairly people who are innocent until proven guilty: They don't deserve to be stuck in jail simply because they can't afford bail. In Salt Lake County, about 30 percent of inmates haven't gone to trial, compared with 61 percent nationally in 2011.

"In other jurisdictions, individuals are often kept in jail before trial simply because they can't afford bail," said David Litvack, director of Salt Lake County's Criminal Justice Advisory Council. "Our [goal] of a fair, just and humane system is to make sure that doesn't happen."

But two recent studies point to problems with the program: The rate of people who are arrested again before trial is more than double the national average, and a higher-than-average number of people don't show up for court.

Authorities plan to revamp the program starting next year. It's an important step, not least because it could affect the county's bottom line. The jail is the county's single largest expense, and each inmate costs about $84 in tax dollars every day. Rising jail expenses are part of the reason behind a 16.2 percent tax hike recently approved in Utah's most populous county.

But while lowering the number of inmates could reduce jail expenditures, the tight budget could also limit the scope of how much the jail can do to keep people out for good.

—

An imperfect system • When Madsen screens an inmate, she's looking for jobs, families, friends — connections to the community that make it more likely the inmate won't commit another crime and will show up for a court date.

New arrivals take a seat on the stainless-steel stool in front of her or another screener, answering questions that begin with basic information, such as age and address, and grow more probing, including mental health, debts, addictions.

The answers can win low-risk offenders a reprieve from cash bonds, saving an inmate or family hundreds of dollars that would typically go to a bail bondsman.

Not everyone makes the cut.

"At this point, we can't release you without a judge's order," Madsen told a dark-haired, tired-looking woman with deep-set eyes who was brought in on a drug-possession warrant on a recent afternoon.

The woman nods in resignation. A sheriff's deputy leads her away.

"With her history, she'll be kind of iffy," Madsen said. The woman has more than 20 prior arrests and several "failed releases" when she didn't appear in court.

The county's pretrial-release program was started in 1974 to alleviate jail overcrowding, part of a wave of such programs that were established beginning in the 1960s in a reform effort to move the nation toward a jail-release system based on more than money.

The U.S. cash bond system is based on the idea that people arrested for a crime can be released before trial, but must leave something of value to ensure their return. For a fee, usually 10 percent of the bail set by a judge, bail bond companies assume the risk. If the defendant doesn't show for trial, the bondsman forfeits the bail money unless the subject can be found. If the defendant does show, the bondsman keeps the 10 percent.

But the cash bond system is imperfect, according to a study by Brigham Young University law professor Shima Baradaran. She analyzed more than 100,000 cases over 15 years and found U.S. jails often release the wrong people. Half of those held in the country's jails before trial are less likely to commit a violent crime than those who are released.

Time in jail can also make a person more likely to re-offend by damaging the bonds that give them a reason to stay on the straight and narrow.

"Spending a lot of time in jail breaks up the support structure: job, transportation, car. It ends up breaking a lot of the things we would like to fix," said Mark Crockett, a former Salt Lake County councilman who brought up the jail recidivism issue this year during his failed run for county mayor.

—

Working with the system • Letting inmates out of jail is one thing, but getting them to the courthouse on time — and ensuring they don't commit more crimes — is another.

"We need to begin to understand that, without some support, people will continue to fail," said Salt Lake County Sheriff Jim Winder.

Along with the pretrial-release program, the county's Criminal Justice Services division, which has a budget of about $8 million, also supervises people who are awaiting trial.

Some are asked to check in with an automated phone system every day, others are given periodic drug tests, and still others are sent to counseling or courses to help them deal with underlying issues, and hopefully address their problems.

Allison Coleman was among those people.

The blond self-described soccer mom with a bubbly voice is also a recovering methamphetamine and alcohol addict with a court record that stretches back to 1995. She gave up the drugs several years ago and later kicked alcohol after a 17-month stay in prison.

"Prison is what changed my life," said the 43-year-old Coleman. "All of a sudden, I lost everything."

In October, though, she relapsed and was arrested for drunken driving. Terrified of a return to prison, she threw herself into the county's supervision program, checking in, attending classes and passing her drug tests.

"I hadn't ever had to deal with stuff like that," she said. "I came to the point where I was working with the system instead of against it."

But it isn't clear the program works any better than cash-bail release. Of those who post bond but are ordered by the court to pretrial services, as Coleman was, 64 percent wrapped up their cases without a failure to appear or a new arrest, according to a 2010 evaluation of the program by the Utah Criminal Justice Center. Of those assigned to pretrial services at the jail, 71 percent complete the program successfully.

Meanwhile, 67 percent of the people who post a cash bond managed to do the same thing on their own, without the program.

In 2011, another study, the Criminal Justice Action Plan, found the portion of people arrested again while awaiting trial, about 45 percent, is more than double the national average.

Those numbers are a concern, said Gary Dalton, director of the county's Criminal Justice Services. "We try to watch that."

As for Coleman, despite her progress and a flurry of letters in her support, she was sentenced last month to another stay in prison.

—

Moving forward • Litvack said he's aware of the issues, and improvements planned to begin next year should begin to fix them.

It's "really to try to clean up at the front end of the system, both in terms of failure to appear and rearrest while on pretrial," he said. "FTAs [failures to appear] are not healthy. … It's not just an issue for the pretrial-service process, it's not healthy for the entire system."

One step, poised to begin in January, is a set of more objective questions for jail inmates. The new questions are more wide-ranging and are based on a two-year process of determining what makes someone a risky bet for release. It's not always intuitive. For example, cash bail is usually set based on the seriousness of the crime, but it's often those accused of less serious crimes who fail to show, according to Baradaran's research.

One way to keep someone from being arrested while awaiting trial is to reduce the wait. An Early Case Resolution program that rolled out last year seeks to cut the time from arrest to case resolution — sentence or acquittal — from six months to one or two.

Prosecutors identify cases that are easy to resolve, such as property, drug and public-nuisance cases, and make a plea offer at arraignment.

Though the jury is still out on whether the program is effective, Litvack said prosecutors make an offer about 70 percent of the time, and up to 35 percent of those are resolved through the program.

"You reduce the opportunity of some to commit a new offense while on pretrial [release]," he said.

But the broader solution is more difficult. It involves creating a new Community Corrections Center that would concentrate on rehabilitation.

"Essentially, it's an opportunity to bring people into an intensive program to make sure that they have a support system on the outside," Winder said. Inmates would have access to a series of mental health, drug treatment, job training and other rehabilitative programs to ensure they have a reason to obey the law once they're released.

The center is planned for a future unit of the county's recently reopened Oxbow Jail, but reopening a new section would cost money — at least $500,000 to start, Winder said. And that's tough in an economy just beginning to crawl out of a recession.

When might it happen? "I just don't have the answer to that," Winder said.

But the sheriff says he knows what won't work. "What segment of our population still believes we can incarcerate our way out of these social problems, these crime problems — I think they need to disabuse themselves of that notion."

Twitter: @lwhitehurst