This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

A man who preserved semen while he battled cancer — a disease that eventually took his life — and bequeathed it to his wife did not necessarily intend to become a parent and qualify his offspring for Social Security benefits , the Utah Supreme Court said Friday.

A federal court judge asked the state's high court to answer the question of whether, under Utah law, Michael Burns' signed agreement to donate the frozen sperm to his wife in the event of his death constituted consent to being the parent of any child she later conceived by artificial means. Now that the state court has answered the question, the case will return to federal court.

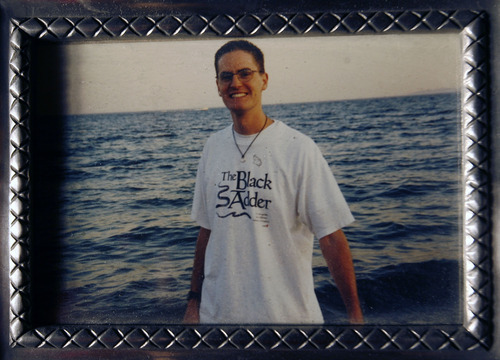

Gayle and Michael Burns had been married about 2 1/2 years when he was diagnosed with cancer. Because the treatment was likely to leave him sterile, Michael Burns contracted with the University of Utah's urology division to preserve his semen. That agreement allowed the semen to be transferred to his wife if he died.

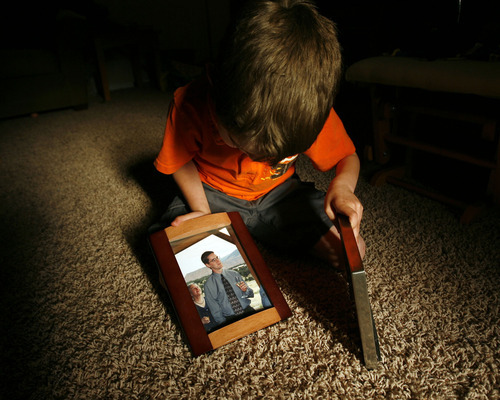

Michael Burns passed away in 2001. Two years later, Gayle Burns gave birth to their son, Ian.

She then applied for social security benefits for herself and the child based on her husband's earnings, but the Social Security Administration denied the applications. An administrative law judge later reversed that decision.

But the Social Security Administration's appeals council later overturned the judge's ruling, finding she was not entitled to the benefits because her son did not qualify as her deceased husband's "child" as defined in the Social Security Act.

At that point, Gayle Burns filed the federal lawsuit that prompted the legal question that U.S. District Court Judge Dale A. Kimball posed to the Utah Supreme Court.

In its decision, the court noted that, under the Social Security Act, benefit decisions depend on applicable laws in the state where a wage earner resided. That has led to varying decisions across the country regarding providing benefits to posthumously conceived children.

Nancy Hart, a Texas attorney, said there are at least 19 children receiving Social Security benefits in the states of Massachusetts, New Jersey, Arizona, Nebraska, Texas, California and Louisiana.

"There are many states that have changed their laws in order to allow posthumously conceived children to be recognized as the legal children of their deceased fathers," said Hart, who fought her own battle to get benefits for a daughter born in 1991 after her husband's death from cancer.

In May, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the right of the Social Security Administration to rely on state law in making benefit decisions.

Under Utah's Uniform Parentage Act, a spouse must agree to assisted reproduction and to be a parent before he or she dies in order to be considered a parent of a child later conceived through artificial insemination.

The statute's definition of parent is "circular and difficult to apply when an individual dies before the conception of a child," the Utah Supreme Court said, but "it is clear from this statute that one's status as a biological father, a status that Mr. Burns held, is legally insufficient to confer on a biological father the status of 'parent.' "

Gayle Burns argued that her husband indicated his consent to be a parent through the signed storage agreement. But the court sided with the Social Security Administration, which said that agreement merely addressed storage and was insufficient to serve as his consent to be a parent. Michael Burns checked a box indicating he was preserving his semen because of cancer treatment, without also checking "prior to artificial insemination," the court said.

While the form then in use addressed at length viability of frozen sperm in leading to a pregnancy, it made no "express declaration" to parent a child later conceived using the semen.

"Something more is required to constitute consent to be a parent of a posthumously conceived child," the court said. "The agreement in question makes no mention of the donor's consent to be a parent of a child using his preserved semen."

Gayle Burns said Friday that the news was "horrible," but not unexpected.

"For two young kids dealing with cancer, we thought that the storage agreement was sufficient enough evidence to show Michael intended to be a father even after his death," she said. "I take heart in knowing that a piece of Mike and I will be here and that Ian has most all of the qualities of his father.

"That the government of Utah and of the United States doesn't recognize the father/son relationship is very disheartening. I know, all who knew Mike know, and Ian knows, that Mike is his father and that Mike intended to be a father, even in the event of his death. That is all that matters."

Twitter: @Brooke4Trib