This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Ogden • Will Calton almost died on Mount Everest three months ago, but now that his battered, bruised and frost-bitten body is healed, he's certain of two things.

No. 1: "I was so close to not making it back."

No. 2: "I would go again."

The 51-year-old owner of an Ogden landscaping company on Thursday recounted the harrowing climb to and from the summit of the world on May 19, a day when four other climbers died on the same route from Nepal.

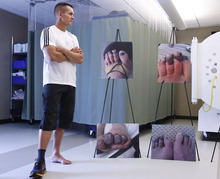

In June, Calton spent 15 90-minute sessions in a hyperbaric chamber at Ogden Regional Medical Center's Wound Care and Hyperbaric Center. His five frost-bitten toes — as well as a collapsed lung, failing kidneys and liver, severe bruises and two broken ribs — are now healed; the father of three children and three stepchildren said he ran eight miles on Thursday.

Some 150 climbers were trying to reach the summit on May 19, a small window of good weather, and some of those toward the end of the "traffic jam" ran out of oxygen, energy and time.

But Calton's small group was ahead of the crowd, leap-frogging from the back by sleeping less than two hours on May 18. They reached the 29,029-foot elevation summit at 8:45 a.m. on May 19. It was windy, 10 degrees below zero and a blue-bird day.

Calton recalls clouds in the valleys below and the elation of reaching the top, but little else about that day.

After five or 10 minutes on the crowded summit, they began climbing down.

Calton was alone when he fell, just 20 minutes out of the highest camp. He speculates he was hit by a rock or passed out from high altitude brain swelling, but he really doesn't know.

Someone — he doesn't know who — cut his rope from the only line for climbers going up or down and used a razor to cut his backpack from his hips. They dragged the unconscious Ogden man 15 feet from the climbing route.

"I don't know why they did it," says Calton, who nonetheless is not bitter. "It's survival of the fittest up there. You have absolutely no extra energy to help anyone."

He likely would have died had his small group's leader, Jeff Reynolds of Santa Fe, N.M., not been descending later and recognized his black and red parka.

For the rest of that day and the next two days, Calton climbed with a Sherpa roped close on either side, his backpack knotted to his frame. His mittens had disappeared; he borrowed a pair from a Sherpa.

Calton recalls one thing clearly: the frequent yelling by those who stayed close, motivating him to keep moving — climbing buddy Tom Burton, of Ogden, Reynolds and the Sherpas.

Burton has since told Calton that he would walk for a minute and rest for 30 seconds. "I remember thinking, 'Why are they so mad at me? What did I do to upset everybody?' " Calton recalls.

It was a slow descent.

A Sherpa arranged for a helicopter rescue, and Calton was lifted off the mountain just above Camp 2, about 22,000 feet in elevation. He was told by the crew that it was the highest helicopter rescue ever.

Calton was flown to Kathmandu, where he was treated for eight days at Ciwec Clinic, and then flew a grueling 23 hours home on commercial flights.

He arrived in Ogden on June 2 and began treatments in the hyperbaric chamber on June 5.

Peter Clemens, director of clinical services, says Calton's recovery in just 15 days of treatment was remarkable.

He and Calton's physician hope to document his frostbite recovery in a medical journal, since it's an ailment for which hyperbaric treatments are still considered "investigational."

"You can work your entire life and not be involved in a story half this cool," Clemens said Thursday.

Calton's insurance paid for his $8,000 clinic bill in Kathmandu and half of the cost of his hyperbaric treatments, nearly $4,000. But Calton and the insurance company are still negotiating who should pay for the $24,000 helicopter ride. —

Hyperbaric therapy

A hyperbaric chamber heals by giving the blood — and thus all the body's organs and tissues — a big dose of 100 percent oxygen. Pressure is increased to two-and-a-half times regular atmosphere — about what a scuba diver feels at 40 feet — and 100 percent oxygen is pumped in.

Most of the Ogden Regional Medical Center Wound Care and Hyperbaric Center's patients are diabetics with lower-limb trouble, carbon monoxide poisoning victims and those with deep wounds that aren't healing well, said Peter Clemens, director of clinical services.