This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Magna • Serena Mounts needed to get vaccinated against whooping cough before she could start seventh grade. Her family has health insurance, but she didn't go to their doctor for the shot.

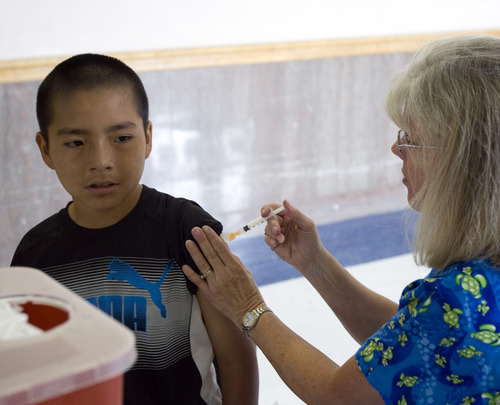

Instead, she recently waited in line at Brockbank Junior High for the immunization.

Starting this fall, the school will be the go-to place for health for the Mounts family, along with many others.

With money from the state Department of Human Services, Salt Lake County is creating a health clinic at Brockbank to treat not just the physical health needs of the community, but mental health ones, too.

A nearby health clinic will offer well-child checks, treat minor illnesses and injuries and manage chronic diseases such as diabetes, which is on the rise.

And the county's Division of Youth Services will double the mental therapy it already provides to the students.

Both services will be available to students and their families, with the idea that taking a holistic approach will improve students' health and academics.

"We build up the entire population with stronger academic support, really building healthy behaviors," said Kelly Colopy, associate director of the county's Community Services department, in describing the county's goals. "It gains its own traction as it moves forward and it becomes a stronger community."

The county also received a five-year grant through the state's 21st Century Community Learning Centers program to expand after- and before-school programs — homework help and social skills classes for kids, parenting and classes to learn English for adults — to two of Magna's five elementary schools, both junior highs and its high school.

The county focused on Magna — it also provides similar services in Kearns — because of the city's huge unmet need.

Adults in Magna have some of the state's highest diabetes, heart disease and cancer death rates, according to Utah Department of Health data. It also has the state's highest percentage of obese adults, at 38 percent.

Magna youth report higher levels of binge drinking and school suspensions than the rest of the county. And the graduation rate at Cyprus is 69 percent, lower than the state average by 7 points.

—

Offering access • Access to health care is the problem, said Cescilee Rall, who has worked at the school as a nurse for nearly a decade and is part of the new efforts. She said few employers offer insurance that covers mental health, and there are few health resources in Magna.

Health data also show that compared to the rest of the state, more Magna families report not going to a doctor because they can't afford it. Half of the students at Brockbank qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.

"I have a lot of hard-working parents. Access to health care is not always easy for them," she said. "This is going to help parents tremendously."

Utah Partners for Health, a nonprofit, will pay the health care costs of uninsured families. Treatment will be provided by the Exodus Healthcare clinic in Magna, which will offer evening hours for working families.

"Diabetes is just becoming more and more prevalent within the community, with lack of nutrition," said Kurt Micka, executive director of Utah Partners for Health, which focuses its efforts on Kearns, West Valley and Magna.

He recalled a 40-year-old father of two who visited one of the Partner mobile clinics. The father didn't know he was diabetic and couldn't afford his blood pressure medication.

"He was a walking time bomb" who "is not going to make it without intervention," Micka said. While that father was from Kearns, "that is repeated every day in some form."

Joey Young took his 12-year-old son to Brockbank for the immunizations provided by Community Nursing Services because he doesn't have insurance. He said that when his family gets sick, they head to the emergency room.

Told about the new health clinic, he said he will use it.

"It would be less expensive to come here," he said.

—

'See beyond today' • Roberta Mounts, Serena's mother, is already a fan of health care in schools. Serena, now 12, was born with a heart defect and had a stent inserted. But a school nurse and teachers noticed she was falling asleep in class, which led to Serena getting surgery to add a valve.

"I would have waited until the annual checkup and she would have lost six months. I'm really pleased with the health care from the schools," Roberta Mounts said.

Serena also has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, so Mounts is happy to know there will be additional therapy available at Brockbank.

"Anxiety is huge with teenagers. Depression is huge with teenagers," said Rall, the school nurse. "Those teenage years are just hard years. We're doing as much as we can to help kids see beyond today."

The county will add 20 more hours a week of behavioral health services, including at night — individual, group and family therapy, and screening and assessment. Those with severe problems will be referred to Valley Mental Health.

The students' problem may be chronic, such as those with a family history of depression, said Carolyn Hansen, director of county youth services. "It could be situational, where mom just lost her job or dad just lost his job or they just got divorced."

The county will track whether students who use the health services or the after-school programs do better in class.

National data suggest attendance improves on the days treatment is available, said Dinah Weldon, administrator for youth and family services at the state Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health, which gave the county the health grant.

"Kids want to access the treatment, " she said.

hmay@sltrib.com Schools and mental health

Brockbank Junior High is one of four schools provided money from the Utah Department of Human Services to create clinics that treat physical and mental health.

Typically, existing school counselors focus on educational needs. The mental health services funded by the state are instead "focused on being able to treat mental illness, trauma, things that if we can get in and involved early won't become a more significant issue," said Dinah Weldon, administrator for youth and family services at the state Division of Substance Abuse and Mental Health.

James Madison Elementary in Ogden, which already had a health clinic funded by Intermountain Health Care, is adding mental health care.

Two-year grants for Canyon Heights High School, an alternative school in Kaysville, and Provo's Dixon Middle School ended this summer. The schools aim to find other partners to continue the efforts.

At Canyon Heights, where the students served are either teen parents or are considered "emotionally fragile," absences due to medical appointments dropped, and 71 percent of students who went to therapy were considered in recovery or made reliable improvements, according to Davis Behavioral Health.

Jody Lee, the social worker at Canyon Heights, said her therapy groups that provided coping skills "were the best-attended of most classes in the school. They were really able to feel like there were other people going through similar things and not feel so alone."

DHS also recently awarded $1 million to agencies around the state to offer mental health services at schools to students who haven't been diagnosed with a mental illness. Insurance won't cover undiagnosed children. But students whose parents are divorcing or have experienced some other type of trauma may still need help, said Weldon.

"It's just like a skinned knee or a [sore throat]. If we can treat it early it won't get infected it won't become something more serious."