This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

In February, Wasatch High wrestler Koen Hyde competed in a tournament in Ogden. The best possible outcome, it seemed at the time, was a Region 10 title. The worst was that the 15-year-old would be acknowledged for participation and have fun along the way.

But when the weight of the opposing wrestler's body pressed against his head, Koen confronted a reality he never anticipated: He suffered a concussion.

"I looked at him and said, 'Honey, I'm here,' " his mother, Rebecca Hyde, said. "He looked up at me and didn't know who I was."

Months have passed, but Hyde said her son — now a junior — still experiences fits of anger, memory loss and severe headaches. Also a football player, he watches his school's varsity games from the sidelines because he's unable to play.

Not long ago, coaches and parents may have largely dismissed Koen's injury, urging him to stay tough, shake it off.

But as researchers learn more about concussions and other traumatic head injuries and their possible long-term effects, school officials, coaches, trainers, medical professionals and even lawmakers are pushing for change aimed at making it safer to participate in youth athletics.

"Do [concussions] affect Utah? Yeah, they do," said Lisa Walker, a teacher and certified athletic trainer at Springville High School.

State-specific concussions data are hard to come by, but nationwide, concussions were the most commonly diagnosed sports injury in 2010-11, according to a National Children's Hospital survey.

Football is a primary culprit and has garnered the most attention as pros such as retired BYU and NFL star Jim McMahon have shared stories of early dementia they attribute to repeated head trauma. Alex Karras' death last week brought new focus to the issue because the retired Detroit Lions defensive tackle was among more than 3,500 former players suing the NFL for failing to protect them from head injuries.

Make no mistake, though, concussions are not just a football issue, according to Utah State University head athletic trainer Dan Mildenberger. "They're a human activity issue. Anytime humans are active, the brain is at risk."

The injury afflicts a range of athletes, from wrestlers to skiers to soccer players. A single blow can cause the injury, but so can the accumulation of lighter hits to the head or body.

Recognizing the risk, the Utah High School Activities Association (UHSAA) in 2010 established a policy that emphasizes education and spells out a process high school athletes must follow before returning to play after suffering concussions.

The 2011 Legislature followed with a law that requires all amateur-sports organizations to adopt and enforce concussion and head-injury policies.

Some fear neither measure goes far enough in protecting young athletes, but Sen. John Valentine, R-Orem, called Utah's approach "a step in the right direction."

"It's not possible to legislate everything," Valentine said. "What you have to do is give a framework so people make responsible decisions."

—

The brain in 'panic mode' • Concussions are complex injuries that can affect both the structure and the function of the brain. Blows to the head can stretch or tear brain cells and cause chemical changes that result in disorientation, delayed verbal and motor response, nausea, slurring of speech and dizziness, among other symptoms.

"The brain goes into panic mode to try to put these things back where they belong," Walker said.

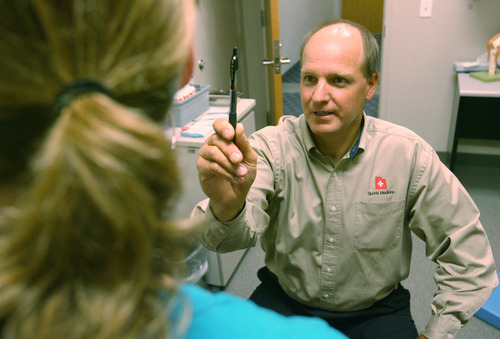

If an athlete reinjures the brain when it has not yet fully recovered, the potential damage is even greater, added Provo physician Karl Weenig.

"The brain needs time to recover. … It's not like a broken arm that you can see a fracture on an X-ray and then you see bone healing," he said. "It's more of a subjective test."

—

Allowing time to heal • Requiring adequate recovery time is key to the UHSAA policy.

An athlete diagnosed with a concussion may not play for the remainder of the day, then must follow a return-to-play plan outlined by a health care professional who also must sign a clearance form.

Return-to-play plans detail steps athletes must follow that include graduated activity, from rest and recovery to light aerobic activity to noncontact drills.

Schools have adopted the policy without major snags, UHSAA executive director Rob Cuff said, and they're largely responsible for seeing that it's enforced.

"We're in constant communication with our principals and our [athletic directors] about protocols and procedures that are happening in their sport," Cuff said. "Word of mouth travels pretty good. Opponents let us know [about an injury], especially if it's an elite athlete. We follow up with the principals and the schools."

Some schools adhere to the policy as it's written. Others take it further.

The UHSAA recommends but does not require baseline testing of student athletes. Through a computer-based series of memorization questions, baseline tests capture a look of an athlete's brain functioning normally. If an athlete suffers a concussion, the test can be retaken and the results compared.

The policy also does not require schools to employ athletic trainers, instead saying athletes should be evaluated by a licensed trainer or "other appropriate health-care professional."

Walker believes trainers, who are also teachers, are best equipped to ensure students who suffer concussions return to play only when they're ready.

Because she is both a teacher and a trainer at Springville, she can observe how an athlete with a concussion is progressing in the classroom as well as on the field.

She knows many schools don't have funding for trainers, but she said professional and college teams always find ways to pay for them.

"Somewhere there needs to be a question in people's minds: Why do we protect professionals and why do we protect adults, yet we don't make it mandatory to protect children?"

Wasatch High, where Koen is a student, is among schools unable to fund a full-time trainer.

Heather Harling contracts with the school to serve as its certified athletic trainer. She said she wishes she could be at Wasatch more often to follow up with concussed athletes and their coaches.

Even though the school can't fund a full-time trainer, keeping the contract position is a priority, said Jason Watt, student-services director.

"I would hate to be in a position where we don't have a trainer," he said.

Watt added Wasatch does now encourage baseline testing for student athletes but doesn't require it because parents have to pay for it.

"We think [baseline testing] is important," Watt said. "[Concussions] are something schools can't ignore anymore."

—

Lawmakers step in • The 2011 Utah law requiring concussion and head-injury policies of all amateur-sports organizations is similar to laws passed in more than 40 states modeled after Washington state's 2009 Zackery Lystedt Law.

It requires organizations to inform parents about concussions and procure signed statements before children can play. Children must be removed from play if a concussion is suspected and cannot return to play without medical clearance.

Valentine and Rep. Paul Ray, R-Clearfield, sponsored the Utah measure that became law because both have firsthand experience with concussions, Ray as a coach and Valentine as an emergency medical technician.

The law's focus on education and process is intentional; it doesn't carry either criminal or civil penalties for failure to comply.

"We didn't want to bully anybody [with the law]. I think it's a good bill," said Ray, who along with Valentine does not plan to push for more restrictive legislation.

The Utah Youth Soccer Association's Bryan Attridge appreciates the framework the new law created and the education about concussions that came along with it.

UYSA has 45,000 children playing soccer on 1,000 teams and "what we know about [concussions] has only been more clear in recent years," said Attridge, director of risk management.

The new law has helped UYSA take concussions more seriously, as the organization should have in the past, he said.

"We're doing a lot better at educating and at least training our coaches," Attridge said. Also, "If the referee suspects a head injury, then they stop play immediately and get the player off the field."

Like the UYSA, other organizations seem to have adopted it with ease, Ray said.

"I think overall it's been accepted very well."

—

More restrictions to come? • Is the Beehive State doing enough?

Some, such as Kearns High junior Colton Grossaint, believe so. The linebacker suffered a concussion when he hit his head trying to sack a Riverton quarterback in a sophomore game last fall. He scored a two-point conversion before exiting the game, but he realized something was wrong.

"Everything just kind of flashed," Grossaint said. "It was really fast and then you just get all loopy."

He missed two games and went through a variety of footwork drills and conditioning tests before returning to action. He thinks that while the new policy has made standards for return appropriately stringent, much of the onus still rests on the judgment of players and families.

"If you go any further, you're trying to force kids," Grossaint said. "Even with the guidelines we have now, there are going to be kids who try to go back too soon. You're talking to a brick wall with some of these kids. Some of them aren't going to listen."

Cuff agreed some athletes and parents still struggle to comprehend the seriousness of the injury.

"We have parents that go out and doctor-shop until they get a doctor that releases him," he said. "That's not the spirit of the rule."

For mothers like Rebecca Hyde, more needs to be done. She recalls signing a form at the beginning of last wrestling season, glancing over information and not thinking much of it.

"I didn't give it a lot of attention at all," Hyde said. "I just thought, 'Yeah, we'd go pick him up,' but I never thought it would ever happen."

Koen didn't take a baseline test before his concussion, so there is no way to know whether he has fully recovered.

"I'm still in the dark waiting to know if Koen is back where he should be," she said.

Brennan Smith and Michael Appelgate contributed to this story. —

UHSAA concussion management policy

Education • Schools are required to educate student athletes and their parents about concussions. Coaches must educate themselves and be familiar with the Utah High School Activities Association (UHSAA) policy.

Baseline testing • UHSAA recommends but does not require baseline testing every two years for student athletes. A concussion history also is recommended as part of students' physical exams.

Action plan • Athletes who show signs of concussions must be removed from practice or games immediately and evaluated by a health-care professional.

Athletes diagnosed with a concussion may not return to play for the remainder of the day, then are required to follow a return-to-play plan outlined by a health-care professional who also must sign a clearance form.

Read the policy online at sltrib.com. —

Protection of Athletes with Head Injuries Act

The act passed by the 2011 Utah Legislature requires amateur sports organizations to:

• Adopt and enforce a concussion and head-injury policy.

• Inform parents of the policy and obtain their signature on the policy.

• Remove children from play if a concussion is suspected.

• Prohibit return to play before children receive medical clearance.

Read the law online at sltrib.com