This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The freshman plugged his radio into an outlet in the wall of his new dorm room. It was the fall of 1970, and the teen turned the dial, expecting to find his favorite station: WDAS in Philadelphia.

Tyrone Medley hadn't traveled much before he left his home in southern New Jersey for a basketball scholarship at the University of Utah. Finding himself some 2,000 miles away from Camden, he heard foreign sounds in a "foreign land," and quickly realized how much his world had changed.

The first time he'd seen anyone wearing a cowboy hat was during his layover in the Denver airport. And as a young, black man from an urban area, he felt out of place in predominantly white Utah. He called his family early that school year and told them he was leaving Utah and returning to the East Coast.

His grandmother told him otherwise.

More than 40 years later, Medley is still in Utah. As he sat in his office in the Matheson Courthouse last week, just days away from retirement, the state's first black judge looked back fondly on a life and historic career that almost never happened. More than once Medley considered walking away from a challenge, only to find success in a second effort.

"Sometimes the difference between being successful and unsuccessful is simply deciding to give it one more try," he said.

—

The court • The atmosphere in New York's Madison Square Garden was "electric" in March 1974.

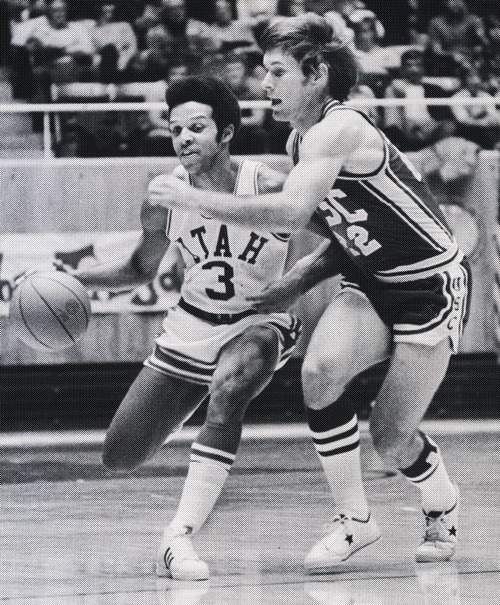

With the help of two of the best basketball players to ever play for the University of Utah, Mike Sojourner and Luther "Ticky" Burden, the Utes led Purdue in the National Invitational Tournament championship game.

For the first time in Medley's college career, his entire family was there to watch him play in the NIT tournament. Medley almost was not.

He describes his recruitment to Utah as an accident. After he helped a first-year head coach named Gary Williams to the New Jersey state title in his senior year of high school, a coach from Temple pulled Medley aside and promised him a scholarship.

He waited for the official letter, but it never came. So, with the other four starters from the team headed off to colleges around the country, a coach made a call to a friend in Salt Lake City. Within a week, Medley had an offer to play for Utah.

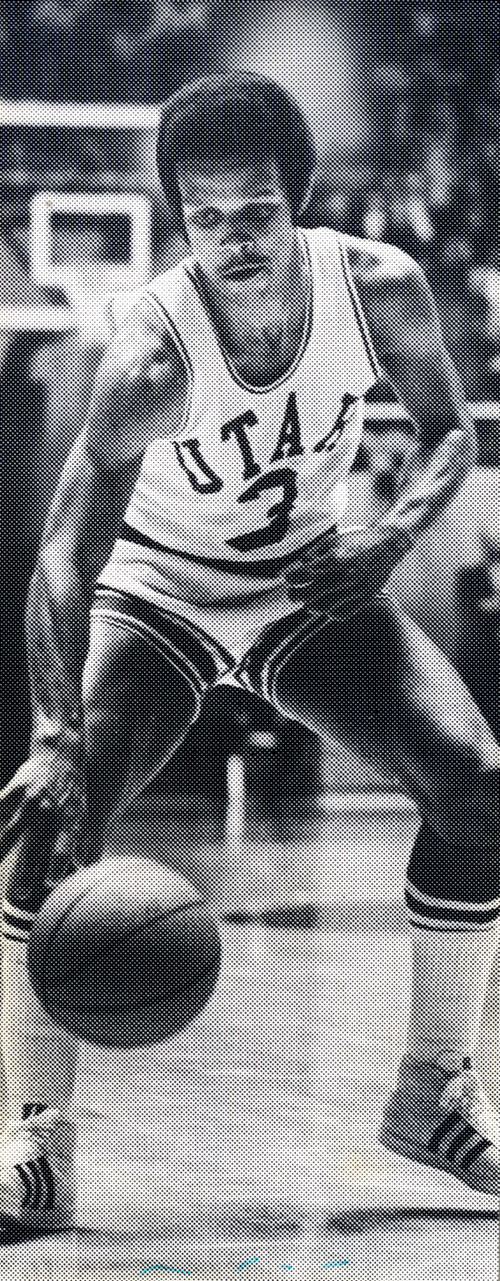

Medley started his sophomore season for the Utes, but was moved to the bench for his junior year for a team that notched eight wins and 20 losses. That spring, he quit the team and told them he would pay his own way for his senior year.

Coaches and teammates talked him back.

"We felt his experience, and with the system we had, Tyrone was the best man for the job," Burden recalled.

With Medley running the floor, the Utes had a fast-paced, high-powered offense and ran through the NIT, beating Rutgers, Memphis and Boston College before making it to the championship game against Purdue.

After Medley fouled out of the game with 13 minutes left, the Boilermakers overtook the Utes for the win. But Medley calls his senior season his most memorable and says the lessons learned on the basketball court — hard work, perseverance, determination — kept him on the path to the courtroom. The following year, as he sat in his '69 Monte Carlo in the parking lot behind the University of Utah law school wondering if he was in over his head, Medley would hark back to those lessons and decide to press on.

"Not quitting and turning away when there are obstacles in the way or the road gets tough — there's no question I've utilized all of those skills to get here," Medley said.

—

The courtroom • If he had stopped to really consider the implications, Medley might never have offered his name for the open spot on the 5th Circuit Court's bench in 1984. Medley knew the state of Utah had never had a black judge, but he hadn't considered exactly what it would mean to be the first.

"I'm confident that I did not appreciate how momentous it was going to be when I applied," he says now. "If I had known that, I'm not so sure I would have applied. ... I've always been a private person. I don't need a spotlight."

Jeanetta Williams, president of the Salt Lake branch of the NAACP, is among those happy to highlight the judge.

"We have a lot of people who look up to him," Williams said. "He shows them that with a lot of hard work, they can be anything they want."

The historic appointment by Gov. Scott Matheson meant a great deal of pressure for Medley to succeed.

"If there wasn't pressure, I had my own pressure-maker mechanism. No question about it," he said. If he failed, Medley worried what the headlines and articles about him might mean for others.

"That piece would really, really hurt me," he said, "because of what it would mean for my race, for my family, not to mention myself."

Medley's appointment and success on the bench has helped make inroads for others, Williams said. But nearly 30 years after his appointment to the bench, Medley says the continuing lack of diversity among Utah's judges suggests a challenge ahead for minority appointments.

Only five of the state's 71 district judges are racial or ethnic minorities, according to the Administrative Office of the Courts. And in his first 24 judicial appointments, Gov. Gary Herbert has failed to appoint a minority.

"I would have hoped that the judiciary over the time that I've been a judge would be more diverse than it is now," Medley said. "But that's the way it is."

He lauds the Utah Minority Bar Association for pushing the issue of diversity on the bench, as the state's minority populations continue to grow. "It's just not something that's going to happen overnight," Medley says. "The community is going to have to hold those in power who make these appointments accountable for a more representative judiciary."

Earlier this month, Herbert appointed two new judges, awaiting Senate ratification, to replace Medley and another retiring judge: James T. Blanch, a Salt Lake civil litigation attorney, and Su J. Chon, an attorney for the Office of the Property Rights Ombudsman, and a Minority Bar member.

—

Off the bench • Those in the legal community say Medley "epitomizes" a good judge, calling him conscientious, polite, and hard working — both on and off the bench.

"He is one of the great judges that we've had here in the last quarter century," said Royal Hansen, the 3rd District's presiding judge. "It's remarkable what he has accomplished and the good will that he has created."

Retired 3rd District Judge Glenn Iwasaki said he became good friends with Medley during 20 years together on the bench.

"From where he came and where he ended up, it's a remarkable journey," Iwasaki said. "He's a wonderful judge and a thoughtful person."

Salt Lake City attorney Peter Stirba said he can always count on Medley to run in his annual charity race.

Medley used to be an avid runner. He ran the Boston Marathon. Twice. New York once. St. George. Long Beach. In all, he's completed the 26.2-mile race more than a dozen times. "That was almost a lifetime ago," Medley says now.

Still, every year, Stirba sees the judge's name among the entrants for the Judgesrun 5k, the charity race Stirba created to honor his wife, 3rd District Judge Anne Stirba, who died in 2001 after a battle with breast cancer.

"I always see him huffing and puffing at the finish line," Stirba says of Medley. "It's not like he was training for it. He would just do it. He'd bring his clerk and some of the court staff. He knew how important it was. It's a real credit to him."

Medley plans to do some arbitration work in retirement. He wants to take on some senior judge shifts. He wants to volunteer. "I'd like to motivate some young folks, to suggest that if I can make it in this community, they can to," he said.

He also wants to get back into running shape.

"I don't know if my body can handle it anymore," Medley said. "It will just shock me if I can get a marathon under my belt."

Still, he wants to push his body, give it one more shot at success.