This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Ogden • Aron Ralston — the Coloradoan whose story of cutting off his arm to save his life inspired the movie "127 Hours" — turned his efforts Wednesday toward saving the country that nearly killed him.

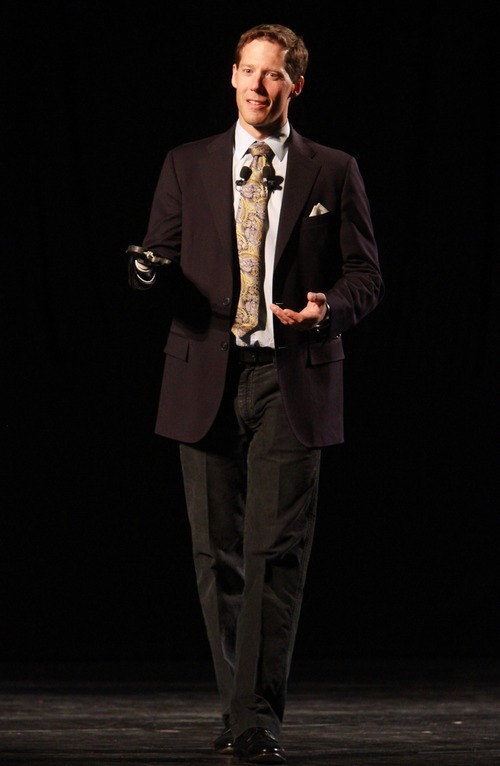

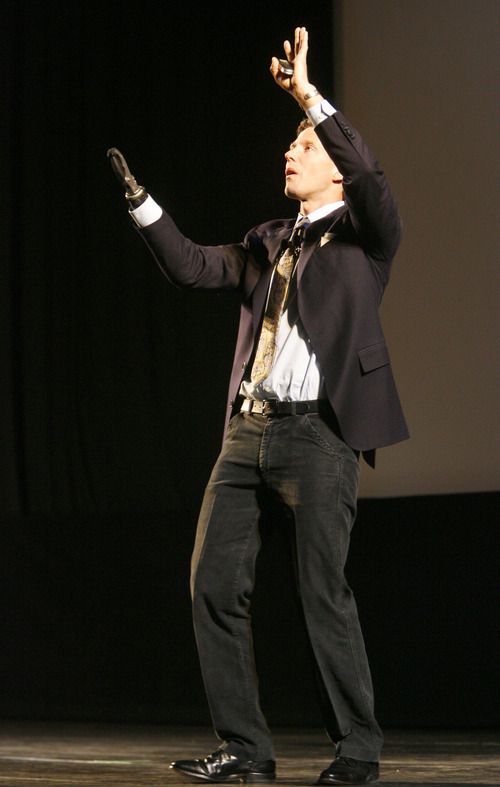

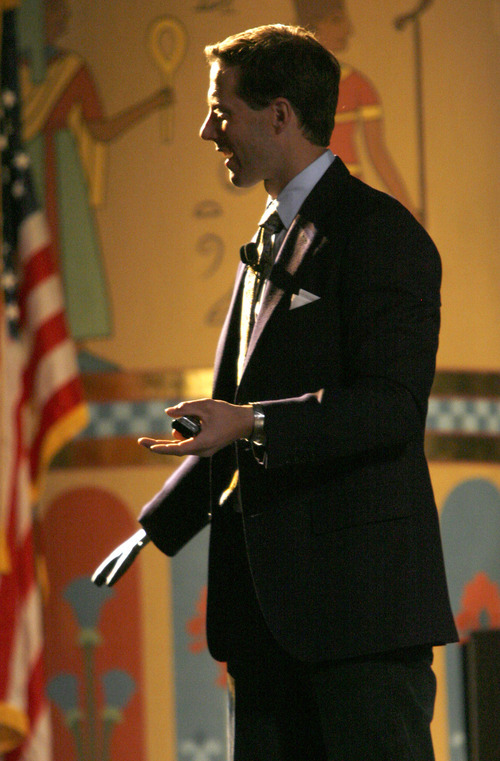

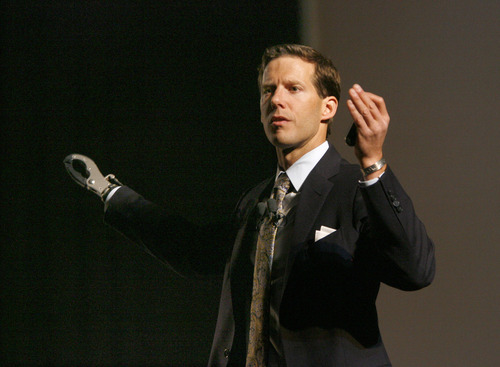

A motivational speaker and outdoor enthusiast, Ralston spoke to about 400 people at Peery's Egyptian Theatre as part of the Grassroots Outdoor Alliance retailers' trade show and as a $13,000 fundraiser for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA). In his speech, he urged President Barack Obama to designate a national monument in southeast Utah, which would include Bluejohn Canyon, where Ralston nearly died. And he called on Utahns to "vote for the canyons."

"Utah has some unique political environments, besides the unique landscapes that we might find," he said. He noted Utah's lawsuits seeking control of roads — some of them rough trails that he called "fake roads" — and a new state law seeking control of the federal lands themselves.

He added that while the nation needs oil and gas, it shouldn't come at the expense of wilderness. Each time he returns to the area where a boulder dislodged and trapped him, he said, he sees a new drilling rig closer to the scene.

Ralston pitched SUWA's Greater Canyonlands initiative to protect 1.5 million acres around the national park, and said Obama should make the area a national monument just as President Bill Clinton did for Grand Staircase-Escalante — the 1996 move that still irks the state's political leaders like few other federal actions.

Ralston said keeping the canyon that took his arm just as it is today is as important as anything in his life, in part because it's where he learned about himself — and what he would do to see his family again.

"It's all potential wilderness," he said of the canyon country, "and yet it's not going to stay that way. It will be [developed] within our lifetimes" without further protections.

In 2003, Ralston was hiking alone in southern Utah — a mistake, he admits, especially considering he didn't tell anyone where he was going — when a boulder pinned his arm against a slot canyon wall. To escape he amputated part of his arm with a pocket knife, and went on to write a memoir that inspired the Oscar-nominated movie.

He has since developed a public-speaking career, and on Wednesday he gave an emotional retelling of the experience: first expecting to die there, then resolving to die on the way out if at all. Recalling the video he took while fearing death, he asked people in the audience to consider what they would say to their own loved ones in such a moment, and to express their gratitude.

He said a vision of himself as a father in the future finally gave him the second wind to wrench his arm against the weight of the boulder and break the bones before carving through muscle and nerve with the dull knife. He used some of his climbing gear as a tourniquet, but said he would have bled to death if a helicopter hadn't spotted him after he emerged from the slot canyon.

He also spoke of his love for the canyons, and the stratification laid down in the ancient Navajo sandstone. He said he sometimes thinks of copying it as wallpaper for his home.

Outdoor industry leaders within Utah, most visibly Peter Metcalf of Black Diamond, have harshly criticized state leadership for pressing to develop minerals in recreation attractions such as Desolation Canyon on the Green River. They've also trashed the effort to take control of federal lands within Utah through a bill passed this year challenging federal rule and setting up a court battle.

The state's rationale has largely hinged on school funding.

Advocates for taking control of federal lands — a sketchy prospect since legislative attorneys flagged the bill as potentially unconstitutional — say federal land managers restrict development that could help pay for schools. Opponents note that there's already a record gas boom on in Utah, and that Wyoming uses a higher excise tax on minerals to fund education handsomely.

Rep. Ken Ivory, R-West Jordan and the bill's sponsor, rejected Ralston's assertions that the state wants unbridled development.

"It's a false premise, this idea that either we develop the energy or close off all access to recreation and our heritage," he said. The state has a $2 billion funding gap to catch other states' per-pupil funding, he said. "We have an opportunity to develop most of our energy and still protect our heritage sites and continue to invite the world to come here."

Gov. Gary Herbert insisted when he signed the bill in May that no one wanted to harm outdoor opportunities — just develop energy sensibly.

"There's no desire from the people of Utah to take public lands and somehow rape and pillage and develop them inappropriately," he said at the time. "We understand there are very pristine vistas that need to be preserved."

But Ralston's call for more federal protections had a friendly reception from an audience that had paid to see him.

"I'm all about it," Ogden resident Angee Farris said when asked about the possibility of a monument surrounding Canyonlands National Park. Preservation is important, she said, "for the generations to come, so they are able to see the beauty and experience Mother Earth at work."