This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The knife was wedged five inches into her back, but the pain wasn't resonating.

After years of pledging undying loyalty to a violent criminal street gang and even becoming a leader, of sending money to fellow gang members in prison, of taking the fall for crimes she didn't commit, it had never occurred to the victim that her gang family might turn on her.

"When I got stabbed, I didn't even feel it," she said.

But with the knife in her back, it became clear to her that it was time to get out.

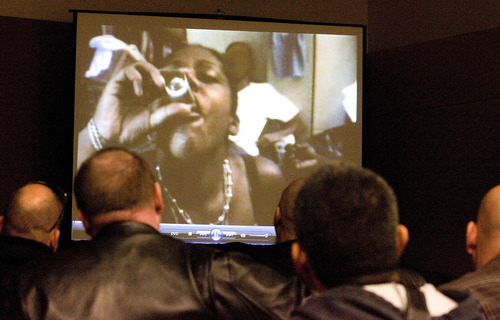

The woman described her time in the gang and the betrayal by the people she considered friends at the 22nd Annual Utah Gang Conference on Wednesday at the South Towne Expo Center in Sandy.

"I started [in the gang] thinking it was cool. And before I knew it, someone was being murdered and I was right in the middle of it," she said.

She spoke on a panel of former female gang members during a session titled "Home Girls Don't Cry," describing the struggle over the past two years to leave gang life behind. She continually changes her phone number, as former gang associates track her down upon leaving jail and prison, wanting to pull her back into the methamphetamine business that kept her afloat financially. She's faced death threats after testifying against a fellow gang member who fatally shot a stranger in Sandy in 2010 during a home-invasion robbery gone awry.

Her family avoids her, worrying about trouble her past may bring to their present lives. Her three children took a backseat to her gang activities, and she's now working to rebuild those relationships. Her heart stops when she runs into old associates, who sometimes surprise her in places she considers safe, like the college she now attends.

"I'm terrified to leave the house at night. All those gang members lurk in the shadows somewhere," she said, declining to provide her name for fear of retribution from her former gang in Utah.

"My biggest fear is that I'm going to befriend the wrong person ... and end up dead. I'm probably more in danger now than I've ever been."

Her story highlighted the perils of gang life for women on the first day of the gang conference, which drew more than 750 participants from law enforcement, the court system, schools and community groups.

The two-day conference is designed to teach the latest gang trends and introduce ideas for combatting gang activity across the state. The annual gathering comes at a time when gangs in Utah continue to evolve in the way they operate, said Rick Simonelli, a U.S. marshal and detective with the Metro Gang Unit, which hosts the conference.

He said a current trend is for gangs to ignore traditional boundaries between each other and collaborate with one-time enemies to advance in the drug trade.

"In Utah, we're seeing more hybrid gangs. It's all about the dope and the money. Wherever they can get the drugs and money to make a profit ... they don't care if you're red or blue," he said.

At the session on female gang members, instructors focused on why women fall into the gang life — and what their role typically becomes in the organization. Of and estimated 1 million gang members in the U.S., about 7 to 11 percent are women, according to statistics and studies from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Utah reports a fairly low number of documented female gang members with only approximately 60 to 100 on the books. But more females are likely involved in gangs. Many girls and women are classified as "gang associates" — which distinguishes them from being called a full-fledged gang member. But they are still participants in gang crimes by serving as lookouts or luring victims to the gang, said Nanon Talley of the state's Juvenile Justice Services, who works with young female offenders.

Talley and Shannon Cox, a supervisor with Utah Adult Probation and Parole, said that girls and women join gangs in four traditional ways: they are "jumped" or undergo a beating to join the organization; they commit a criminal act as part of a "mission" to join; they are "sexed in," or are gang-raped by several men before being declared a member; or are "blessed in," which means they are allowed to join the gang because they have family members who are a part of it.

Talley and Cox said the number of girls and women "sexed" into Utah gangs is low; that most female gang members report other initiations into gangs.

But that doesn't mean sexual violence against female gang members doesn't occur. Cox recalled a client who decided to leave her male-dominated gang after a prison stint. She was taken outside a halfway house and held hostage for three days and raped by more men than she could count, Cox recalled.

Cox said a disturbing trend in Utah is the growing number of multi-generational gangs. At the Utah State Prison, there are grandmothers, mothers and daughters who are all incarcerated at the same time because of gang involvement, she said.

"You're looking at a cycle that will keep perpetuating itself unless we do something," said Cox, adding that community intervention is essential. Once law enforcement becomes involved, it is often too late for some gang members, she said.

The woman on the panel who spoke of being stabbed said she became involved with her gang in 2005, after growing up in an abusive home and ending an abusive marriage. A cancer scare led her to abuse drugs, and her gang-involvement fueled the habit. She thought she found love with another gang member, but soon learned the relationship wasn't real and had been orchestrated to make sure she wasn't sharing information about the gang with police.

Rebuilding her life is an ongoing struggle, she said.

"I was pretty cocky. But at the same time I was pretty naive," she said. "There are plenty of times I could have ended up dead and it's just from being around these people."

"I'm still working at trying to better my life," she said.

Twitter: @mrogers_trib