This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

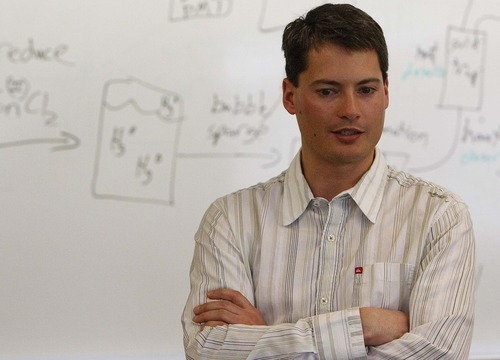

Chasing spiders and pulverizing them sounds like kid stuff. But for Westminster College undergraduates like Jim Goodman, it's scientific research that will get his name on peer-reviewed studies and open doors to graduate school.

Goodman is among a cadre of science students investigating the movement of mercury through Great Salt Lake ecosystems. His project, one of several mercury-related studies led by Westminster faculty, measures levels of the industrial toxin in orb weavers, those big-bodied spiders that proliferate near the lake's shorelines in pursuit of brine flies. Preliminary data indicate far greater mercury concentrations in spiders found at the lake's Antelope Island than those at Utah Lake.

"You can see these spiders bio-accumulating mercury like gangbusters. The next question is, what eats the spiders? No one knows," said Bonnie Baxter, director of the college's Great Salt Lake Institute. "It's this amazing place and it's so understudied."

To advance this line of research, the 4-year-old institute recently landed a $250,000 grant from the W.M. Keck Foundation, tripling its resources.

"It's so competitive. You can't just apply. You have to be invited," Baxter said. "It's an honor to be recognized by [Keck]. They follow the top trends in science education. If we have the Keck seal of approval, others will be willing to take a chance on us."

In other research, the institute is studying brine shrimp genetics and the microbiology of the lake's hypersaline waters, which contain no fish. A biology professor, Baxter investigates the bacteria that inhabit the lake's North Arm, rendering the water a rusty red.

—

Why mercury matters • For years, scientists have documented elevated mercury levels in the Great Salt Lake, primarily deposited from mineral smelting. Analyses of lakebed sediments indicate deposition levels increased sharply from 1900 to 1950, according to Utah State University biologist Wayne Wurtsbaugh.

"Since then it has been decreasing and we think that it is improved smelter technology. The levels are one-quarter to one-fifth of their peak in 1950," said Wurtsbaugh, a professor of watershed sciences. But the mercury remains in the lake where microorganisms convert it to its toxic form, known as methyl mercury, which can be absorbed into organic tissues.

"People wonder what does it matter. We don't get fish out of the lake. We don't drink it," Baxter said. "If [mercury] is bio-accumulating in birds and flying somewhere else, it enters another food chain. We have to be responsible citizens because we are a part of a bigger picture."

Yet not much is understood about what happens to mercury once it gets in the lake. And few seem to notice except when it appears in game birds that can wind up on people's dinner plates. Mercury is linked to birth defects and nervous-system damage in humans. Methylmercury already has been documented in ducks, prompting the Utah Department of Health to warn against eating too much goldeneye, cinnamon teal and northern shoveler.

"We have just touched the tip of the iceberg in regards to mercury cycling in the lake. Bonnie's expansion into the terrestrial systems is a good idea," said David Naftz, a biochemist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Prior research has documented high mercury levels in the lake's two aquatic invertebrates, brine flies and brine shrimp.

The spider study is the "creepy" brainchild of Great Salt Lake Institute coordinator Jaimi Butler, who has been intrigued by the plague of orb weavers that blooms every summer near the lake.

"I see this incredible biomass out there but I couldn't find any information about it," she said. Orb weavers, named for their round webs, make up the largest spider family, known as Araneidae, with more than 3,000 species.

Because they inhabit the top of the invertebrate food chain, orb weavers would be the bugs exhibiting the greatest mercury accumulation.

Spiders dine voraciously on brine flies that hatch in the lake and swarm the shoreline by the billions. Butler's idea is to quantify the movement of mercury, taken up by fly larvae, from adult flies to the busy spiders. She recruited Goodman to gather spiders and assist Frank Blank, a new professor of biochemistry at Westminster, in processing the samples.

—

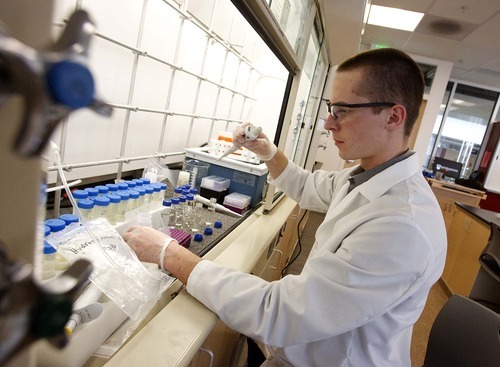

It's about birds • In the lab, the team smashes up the spiders with a Teflon-coated rod and dissolves the material in an acid solution. After this mixture is vaporized, the team records concentrations of elemental and methylated mercury with a device called a cold vapor atomic fluorescence spectrometer.

"The data we've collected is significant enough that we need to do something with it," Black said. "It will be one of the few times demonstrated that you have substantial biomagnification of methylmercury in terrestrial ecosystems. Ultimately we are interested in what happens to the birds."

The lake is a major stopover and breeding ground for migratory birds, which winter here by the millions, as well as a home for many year-round residents.

"The bushes start to move, there are so many spiders out there. It's a buffet for some of these birds. You can potentially have the biomagnification [of mercury] we see in the aquatic species," Naftz said.

Westminster biology professor Christine Stracey hopes to determine which birds eat the spiders. This spring, she and her students will study western meadowlark, redwing blackbirds, cowbirds and other land-dwelling birds on Antelope Island. After catching them in nets, they will draw blood samples and attach uniquely patterned bands to their legs so they can be identified by sight. The team will compile winter survival rates, determine whether a male and female pair stay together, and track birds' movement between Antelope Island and the mainland.

In a related study, Westminster students are helping discover how mercury in the lake becomes methylated. Scientists believe microorganisms that thrive in anaerobic conditions combine elemental mercury with a hydrocarbon molecule, but no one knows which Great Salt Lake bacteria are responsible, although Baxter has some suspects in mind.

Her student Tom Stevens isolates microbial species recovered from lakebed samples, kept in canning jars in a lab fridge. This group hopes to sequences these organisms' DNA and culture them in the lab. Collaborators at Rutgers University will then observe how these isolated microbes interact with mercury.

Mercury and the Great Salt Lake

Metal smelting has left a toxic legacy of mercury contamination in the Great Salt Lake, but not much is known about how this substance moves through the ecosystem. Armed with a new grant, Westminster College is conducting research that may shed light on how mercury moves up the food chain. One project is quantifying the levels of mercury accumulating in spiders that dine on the lake's brine flies.