This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

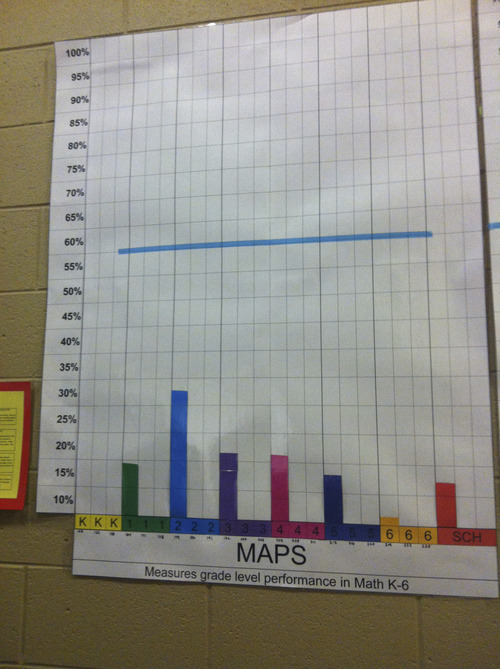

Ogden • Brightly colored bar graphs line the hallway at Odyssey Elementary, charting students' progress in reading, math and attendance. In most grades and subjects, the bars stop far short of a blue line marking the goal.

"When you're at 15- or 20-percent proficiency, that's not an easy thing to publicly own," said Ogden Superintendent Brad Smith. "On the other hand, it's important and it's imperative. … If you don't acknowledge where you're at, there's no way to know where you're going."

For Smith, who has never been an educator, the only option for Ogden schools is up.

In his first five months as superintendent, Smith announced bold goals for Ogden — one of only two districts in Utah facing federal sanctions for failing to meet student achievement goals district-wide.

He came to the job at a tenuous time. In August, former Superintendent Noel Zabriskie abruptly resigned. Teachers were still smarting from a summer standoff with the school board that left them without a negotiated contract.

The board looked no further than its own membership in quickly choosing Smith — an attorney with no teaching experience. Smith, who did not vote on his selection, resigned from his board position.

"There will always be people looking at the superintendent and saying, 'You're a non-educator.' For those who can overcome that, there are great things that can be learned from his experience," said Ogden Board President Don Belnap. "He is just taking the baton, and he is running as fast as he can to make things better in the Ogden School District."

Smith, with the help of district and school administrators, has rolled out a list of "guarantees" or promises of what the Ogden district will deliver to students, parents and taxpayers "come hell or high water," he said in an interview.

Starting this year, Ogden will score above the state average on standard exams known as CRTs. And in two years, it will be the highest performer on the Wasatch Front, Smith pledged. That means in just one year, Ogden has to move from 52 percent of students scoring proficient in math, language arts and science, to 74 percent. To have the highest scores on the Wasatch Front, Ogden will need to gain another 11 percentage points, Smith said.

"Wow. That's a very rigorous goal," said John Jesse, director of assessment and accountability at the State Office of Education. "At a district, to see a 20 percent change, something significantly different has to happen. You can't fake it."

Smith also plans to boost the district's lackluster graduation rate — 63 percent in 2011 — to above 90 percent in 2013. And he wants 95 percent of kindergarten through third-grade students reading on grade level by May 2013. In 2011, 54 percent of Ogden's third-graders were reading on grade level at the end of the year. He also hopes to stop the annual net loss of 1,200 students who choose to attend schools outside Ogden district.

Ogden's poor performance, at least in part, has been seen as a sign of the district's challenging demographics. It has the highest poverty rate among Utah school districts, with 74 percent of students qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch. More than a quarter of its 12,652 students are English language learners.

Smith plans to accomplish his goals without boosting the district's budget, which includes $6.9 million in federal grants to be spent over three years for five low-performing schools that face sanctions under No Child Left Behind. But he insists there will be no excuses if Ogden falls short.

"We will not use poverty, race, funding, morale or prior history to excuse things within our control," his list of guarantees noted. "We know that history is not destiny."

—

Reaching out to teachers • To craft the comeback he wants, Smith needs teacher buy-in. In fact, when asked how he will get the dramatic gains, his first answer is to change district culture so everyone feels accountable for student achievement. That includes publicly sharing test scores by teachers, which is already happening at Odyssey and Dee elementaries. Odyssey shares classroom data at community council meetings and will begin adding it to the hallway charts in the next few months.

"I think it is great," said Cara Nielsen, a fifth-grade teacher at Odyssey, of posting such data. But she believes it's there to motivate students more than teachers. "Here at Odyssey, we're pretty motivated to do the best we can with the students we teach," she said. "We're trying to do more and more to have these kids take ownership of their work and their scores so it's no longer a secret in a binder. Parents can see it, too."

Smith is still working to mend a sometimes-rocky relationship with teachers. As a member of the Ogden school board last summer, he was among the most vocal defenders of the board's decisions to phase in performance pay for teachers and ditch negotiations for a 2011-12 contract with the Ogden Education Association (OEA). Hundreds of teachers rallied in protest, and 2,000 people signed a petition urging negotiations. But ultimately teachers agreed — under threat of losing their jobs — to sign a take-it-or-leave-it contract by July 20.

Many remain skeptical of Smith.

"[Board members] didn't even look for someone with any educational experience at all. They simply put in one of their own," said Max Ferguson, a former fourth-grade teacher at Lincoln Elementary. Ferguson, now retired, said he felt like an "indentured servant" after the summer contract dispute. A few days after the board appointed Smith, Ferguson gave Lincoln Elementary 30 days' notice.

"I didn't care to work for someone with less [qualifications] than I had as far as educational experience or university credits," Ferguson said.

Some teachers privately refer to Smith as "the emperor," said one Ogden teacher who asked not to be named because she feared repercussions at work. Teachers were startled when, in his second week on the job, Smith shuffled several administrators at the district's junior and high schools.

"It's left a sense of instability," she said. "Many people are afraid to speak up because they're afraid they're going to get transferred as a punishment."

But OEA President Doug Stephens, a Ben Lomond High teacher, gives Smith credit for resuming negotiations for next year's contract. Communication has improved, Stephens said, now that both sides have attended trainings on bargaining and the superintendent and board members participate directly in meetings.

"We've made some great steps forward. [Smith is] willing to listen, and he's willing to work with us," Stephens said. "We realize that there's a scab there that got ripped open. We've got to make it heal."

Smith also has sought input from teachers and administrators on how best to implement a board mandate to begin phasing in a performance-pay system in two years. The district has a task force of about 30 members, including two board members but mostly teachers, who meet monthly to look at performance-pay models nationwide and discuss what pieces might work well in Ogden.

"It feels like our voices are being heard," said Nicole Lovell, a fourth-grade teacher at Taylor Canyon Elementary who is on the task force. She said Smith attends most meetings, asking thoughtful questions and listening intently to others' comments.

"One of the things I like about him is I like the idea of high expectations," Lovell added. "As a teacher, I have high expectations of my students so that's something that's welcome."

—

Making the grade • Besides a focus on student achievement, Smith hopes to strengthen leadership at the school and district level. That's why he shuffled several principals at the start of the year, he said. He felt the changes, proposed by district staffers, ensured effective leaders in every slot.

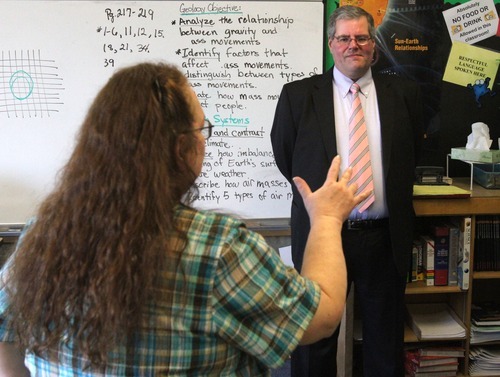

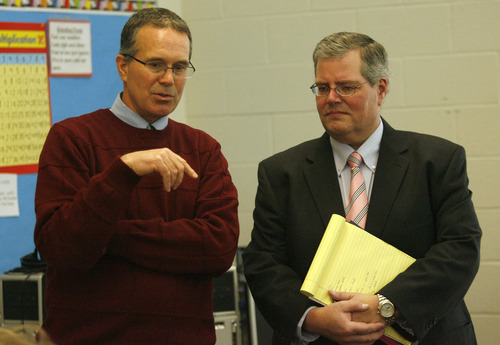

Smith, along with some district administrators and principals at Ogden's lowest performing schools, is getting coaching from the University of Virginia's school turnaround program, which offers business executive-style training for educational leaders. The university also sends specialists to the participating schools — Ogden High, George Washington High, Odyssey Elementary and Dee Elementary — twice a year to evaluate practices and offer suggestions.

"We absolutely believe — and research backs this up — that a high-impact, strong leader at the school level is absolutely critical, especially in a turnaround situation," said LeAnn Buntrock, executive director of the University of Virginia's Darden-Curry Partnership for Leaders in Education. "We're looking for people who can create a vision and communicate that, who can start to change the culture and raise the expectations for everybody."

Buntrock has been impressed by Smith's openness about his lack of knowledge of education and his eagerness to learn.

"There's no doubt in my mind that he is very passionate about this, that he is in it for the right reasons. He really cares about the kids and the teachers and the parents," Buntrock said. "He also brings a very fresh perspective."

Maria Mendez, PTA president of Odyssey Elementary, said she feels the district is offering more support to teachers at her school. She is hopeful that an after-school program, efforts to get more parents involved, and such incentives as a student-of-the-month award will help improve performance at Odyssey. She has met Smith once, at a PTA meeting.

"I think that time will tell" if he is a good fit for superintendent, she said in an interview in Spanish. "On the other hand, I noticed that he wants all kids to graduate from high school. He does not want any child left behind. And that, by itself, is very important."

Ahora Utah Editor Josie Pereira contributed to this report. —

About Brad Smith

Age • 45.

Family • He and his wife, Debbie, have three children.

Education • Smith, a self-described "product of Utah public schools," graduated from Cottonwood High and earned his bachelor's and law degrees from the University of Utah.

Career • An attorney, Smith has worked as a Brigham City prosecutor and started the Ogden law firm Stevenson and Smith in 1997. He joined the Ogden school board in 2007 and was named superintendent in August 2011.

Salary • $120,000 a year, plus up to an additional $30,000 if he meets goals set with the board.

Fun fact • Smith loves to cook and has helped Scouts cook a dutch-oven lobster dinner at camp. At home, he and his family enjoy making sushi, Chinese food and Italian dishes.