This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Three weeks ago, Occupy SLC set up camp in Pioneer Park. Now, as the coldest night of fall begins, protesters are trying to iron out their relationship with the park's homeless and are watching as their counterparts in other cities clash with police.

Salt Lake Tribune reporter Erin Alberty will be spending the next 24 hours at Pioneer Park, observing day-to-day activities, meeting the people there and learning how the Occupy movement plans to shift into a new season.

If you have questions for Erin's consideration, leave comments on this story, direct message her on Twitter (@erinalberty) or email her at ealberty@sltrib.com.

Stay tuned for updates throughout Wednesday night and Thursday.

Latest tweets from Erin Alberty (newest at the top)

Latest update:

6:50 a.m.

The kitchen seems to be the heart of volunteer enthusiasm at Occupy SLC. It also seems to be a place where the large homeless presence isn't an issue. For the many points of disagreement and dissent, everyone here seems to agree that food should be shared. Cooks and servers arrive well before dawn to light the propane stoves. Bread and peanut butter and jelly are set out. Volunteer Michael O'Hare scoops simmering oatmeal into bowls and greets Occupants with a "good morning" while Angelo Dion vigorously cleans up the equipment.

"It reminds you of the old pioneer days," Michael says. "They all stayed in Pioneer Park."

Early in the morning, nearly all the breakfasters are familiar faces from the Rescue Mission, where Michael lives. Angelo, a 49-year-old truck driver who is on home leave, says he came to Occupy SLC with his wife because he is frustrated with imbalance of power.

"You have a tiny percent of people that have been allowed to manipulate a lot of things that affect all of us," he says.

But he is most moved by the community solidarity. A rancher brought a cow's worth of meat a few days ago, Angelo says. Today, a man drops off a collection of industrial tarps. When Angelo asks his name, the man glares at me and warns me not to write it down.

"A lot of people work for people who benefit from the system we're against, so they be public," Angelo says.

Many of the kitchen workers, like Michael, come from the shelters to the park only to volunteer. Stacey Allen, 55, moved to Salt Lake City a month and a half ago from California with her steelworker husband because they heard there were more jobs in Utah. Neither found work and they moved from motels to a shelter. She shows up to manage the camp kitchen every day for one reason: "I heard they needed help in the kitchen." Her husband used his construction skills to rebuild the camp kitchen.

At breakfast, it is a little hard to imagine other cities' Occupy camps, the ones that are farther removed from their homeless centers.

The harmony in the kitchen doesn't last all day. Before 8 a.m., a domestic dispute between two homeless Occupants leads to a shouting match, threats to blow up someone's tent, and a trip to the courthouse for a restraining order. Volunteers step out of the kitchen and shake their heads.

"I hate to see that because there have been good people who have come along. They want to help," Angelo says. "I don't want this to implode because of stuff like that."

The group goes back into the kitchen tent, where people are waiting in line for their oatmeal and good mornings.

2:36 a.m.

It seemed mostly quiet here after midnight. At least for tonight. Freezing temperatures will do that. Sasquatch perked up for another round about 1 a.m. Someone woke him up, and then someone else made the mistake of telling him to lighten up. This turned into an argument over whether the protest was too prissy and nice.

"This is how you protest!" Sasquatch bellowed over the park. "I'm protesting for the 99 percent, and I've got a big mouth! If nobody likes me being awake, stop being [expletive]!

"[Expletive] the homeless! And them!" he shouted, pointing to the quiet-hours zone. "I bet half those tents are empty! This is why this protest is a joke. Everyone is here for their own reasons."

Now another person is up and about. A man is standing in the Sacred Space, mumbling about heaven and hell. He leaves the circle, which is marked with caution tape and a paper heart, and starts bobbing and weaving down the sidewalk, shouting incoherently.

It isn't clear whether the man is on drugs, mentally ill, marching to his own drum or an active part of the Occupy demonstration. I want to ask, but someone already has stopped him from following another reporter to her van. That got him agitated about lost opportunities, and I decide an interview can wait until morning.

Previous updates:

5:15 p.m.

To start my Pioneer Park overnighter, I ask demonstrator Adam Lund for a quick tent city tour. There's a kitchen, library/school, info booth, first aid tent, sacred space (open circle for meditation and worship), a "quiet space" tent community to the west and a "night owl" tent community to the east.

And then there is a smaller cluster of tents to the north. Those are "I don't know, the nonconformists?" Adam speculates.

About this time, a shouting match breaks out among some men near the Night Owl zone.

"Are they part of the group?" I ask as one of the men storms off. Adam doesn't know. When you claim to represent 99 percent of everyone, you can't really exclude guys who fight in the park or say they don't speak for you.

"I wouldn't even try to," Lund says.

6:04 p.m.

The 6 p.m. march starts a little late. Occupant Daniel McGuire wants to go to the Salt Lake City police station to have a vigil in honor of the Oakland, Calif., demonstrators who struggled with police Tuesday, and to thank SLCPD "for not shooting us." He proposes a route through downtown.

"Consensus check?" McGuire asks the 20 or so people holding signs.

Several hold up their hands and wiggle their fingers.

This is Occupy's version of Robert's Rules of Order. A poster at the free school/library tent shows some of the hand signs used for discussions. Upward wiggly fingers mean you agree. Downward wiggly fingers mean you disagree. Forearms crossed in front of your chest means "nuke," one demonstrator tells me — "Stop talking that way or I'll leave." Pointer finger raised means you have a point of information, two raised fingers mean you have a question. Fingers in an "O" mean you're off-topic.

7:37 p.m.

About two dozen people are marching to the police station. There is one dad with two children. A middle-aged couple. Several men and women in their 20s and 30s. A guy in a gorilla mask. A woman named Moonflower.

The group chants "Hey, hey! Ho, ho! This corporate greed has got to go!" and carries signs with such messages as "Socialism for the rich, socialized debt for the 99%?" A woman suggests "1-2-3-4, Obama is a corporate whore" and then disclaims, "But I don't mean to insult whores." One man stops to pick up a floundering butterfly that has apparently been struck by a car. He's just moving it to the grass, he says.

But the march is to focus on the relationship between protesters and law enforcement after clashes in Oakland. A motorcycle officer passes the group at 200 South and State Street.

"We love you!" shouts Daniel McGuire, who suggested the police-station march. "Thanks for not shooting at us!"

At the police station, candles are lit and Moonflower plays "All Along the Watchtower" on her guitar. McGuire calls the group together to discuss the Oakland police action, which he watched on YouTube.

"I saw total brutality," he says. "But we haven't had any police violence in Salt Lake."

"Yet!" two people interrupt.

On police friendliness, like many issues, some Occupants disagree.

"Wait until they get the order to fire," one woman grumbles.

After the Lord's Prayer and a Jewish blessing, an officer comes outside. McGuire tells her the group wanted to thank police for not being violent.

The officer brightens.

"Oh, this is a friendly thing?" she asks. She says she saw placard-carrying protesters gathered outside the police station, "but I heard you playing guitars and thought, 'Well, they don't seem unhappy.'"

Some Occupants recognize the officer from the department's previous visits to Pioneer Park.

"Thank you for not killing us or shooting us," McGuire says.

"Right now there's nothing planned," she assures them. McGuire invites the officer to take off her badge and join the Occupants if she is ever ordered to use force against peaceful protesters. She says she'll always represent the city and would ask only that the candles not be left burning next to the decorative planters because it's a fire hazard, and that doesn't look good in front of a public safety building.

"We agree to that," McGuire says, as others approach the candles to collect them. But some of the demonstrators hesitate.

"Don't agree to anything," one woman warns.

"Don't talk to the cops," another calls out as she walks away. A few people offer to wait outside the station until the candles have burned out and collect them, as a compromise.

McGuire says dissent is part of the movement, and he's fine with it.

"None of the group speaks for me, and I don't speak for the group," he says.

9 p.m.

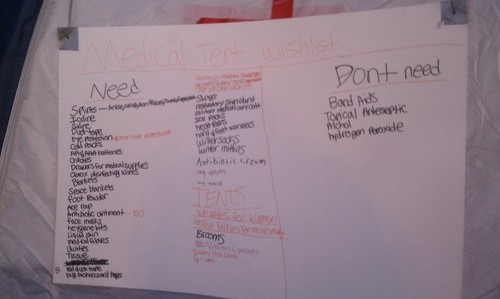

Back in Pioneer Park, Cynthia Cook is seated behind a table with a walkie talkie in hand. A week ago, she was living at The Road Home shelter. Now she fields donations for the camp and keeps inventory of medical supplies.

Cynthia says she came to Pioneer Park because this is where her wheelchair battery died, but she stayed for the cause. She and her family — who also lived at The Road Home — missed a TRAX train and came to the park to recharge her chair at the bathroom outlets before rolling back to the shelter.

"I saw some people I knew, and they asked me if I wanted to help," says Cynthia, 52. She got a donated tent and has been at Pioneer Park since then. Although the temperature is dropping toward 30 degrees, she says she is happier at the camp — for now.

"It's better than having my personal belongings spat on," she says. When her friends lost their Rose Park apartment in April, the Road Home "was like a family" Cynthia says. But shelter life is up and down; it all depends on the other residents.

So does life in the camp. The drunk people are annoying, Cynthia says. But she, her adult daughter and their boyfriends have a good patch of park near the health shelter. They are the cluster of tents previously described to me as maybe "the nonconformists."

"The quiet hours people are over there, the party people are over there, and we're right in the middle. We try to defuse the situation."

The campers here help out in the medical tent, gather and disburse donations, work security, and collect lost-and-found items, Cynthia says. They use the walkie talkies to call people to help gather donations, break up fights and get supplies.

"I wouldn't say it's fun here, but I feel like I'm helping with a worthy cause," she says. "The preamble of the Constitution says 'We the people.' Not 'We the muckity mucks.' Not 'We the rich people.' Not 'We the middle class.' Not 'We the poor people.' It's 'We the people.'"

10:45 p.m.

It would happen that the first brawl of the night interrupts my interview with an Occupant who is focused on unifying the disparate people and causes at Pioneer Park.

Jesse Fruhwirth, of City Weekly fame, is also probably the most media-savvy person in the group. When the Occupants heard the city would be suspending their permits last week, he says he started Tweeting to reporters right away. By 2 p.m. the next day, the police chief said the whole thing was a rumor, and the permits would still be issued. Jesse thinks it was all about pressure.

The latest PR challenge has been friction within the Occupation as to how to interact with the homeless people who have been in Pioneer Park for years.

"It was disconcerting and difficult for some people who didn't have any experience with street life previously," Jesse says.

Also, the permit is for public demonstration, not just camping for camping's sake, Jesse says. That begs the question of whether non-demonstrators (i.e. the homeless) should be pitching tents under the Occupy SLC permit. From a black-and-white policy standpoint, the easiest answer might be "no." But that's just not very 99-percenty.

Instead, Jesse has been trying to legitimately involve the homeless in the demonstration. Of the 150 people or so who are camping at Pioneer Park, about 100 are actively protesting, Jesse estimates. About half of those were homeless when the Occupation began, he says.

The 50 or so nonparticipants camping in the park mostly have substance abuse or mental health problems, "or really heavy chips on their shoulders from years of being victimized," Jesse says.

At this moment, the chips start to fly. Yelling can be heard from the no-quiet-hours side of the park, and a teenager runs over to get someone to help break up a fight between two drunk guys, one of whom is called Sasquatch.

Volunteer watchmen block the two men from each other and then escort them to separate corners of the park. Jesse talks with Sasquatch while he cools off.

"It's interesting to talk to people who have never seen a nonviolent solution to a conflict," Jesse says a few minutes later. "What we're doing with poor and homeless people doesn't stop at questions of food and shelter."

11:20 p.m.

Nathan Clark, 18, runs over to the quiet-hours section of camp to get Hawaii, the volunteer security guard.

"Cowboy dropped a guy," he says, referring to a fight on the far side of the park, where there are no quiet hours. Also known as "the party side" or "the night owl side." Right now it's the yelling side. A guy called Sasquatch got into it with someone else. Cowboy, another volunteer security guard, has tried to break it up, but now he needs help. Enter Hawaii.

By the time we get there, Cowboy is escorting one fighter away, presumably the one he just "dropped," but Sasquatch tries to chase after them. Hawaii blocks Sasquatch and holds him back, so Sasquatch goes to the curb to cool off. Cowboy can be heard telling the other guy, "I'm just trying to help you!"

"This always happens," Nathan says.

"What happens?" I ask.

"Well, that guy's drunk and that guy's drunk," he says. "That's basically it."

From the curb, Sasquatch is yelling again.

"[Expletive] the homeless!" he shouts.

"You're homeless, too," Nathan retorts.

And so is Nathan. He says he's been on and off the street since he was 7 and moved to Salt Lake City from New York State two months ago. He says his mother, now dead, was involved in the occult. He raises his shirt to display the faint scar of a pentagram on his torso. He says his mother was ill for a long time, and he was her caregiver. Now he volunteers at the medical tent. His camp walkie talkie begins to squawk. It's Cowboy, asking where to find the band-aids.

"I had a bed at the Road Home, but I lost that to be here with the cause," he says. "In my opinion, the government sucks. Politicians suck. The president is stupid, and the health care law is terrible. It all needs to be fixed, but Wall Street is the place to start."

12:54 a.m.

Security seems to be the single biggest issue for Occupy SLC. In message, it's corporate greed. But in day-to-day talk, I've heard more about law and order than anything else at Pioneer Park.

Not that I feel unsafe here. I am sitting in my car with my key in the ignition, the doors unlocked and the overhead light exposing a pile of expensive electronic reporting tools. No one has bothered me.

But it is Pioneer Park. It was Pioneer Park before the Occupants occupied it. Every city has a difficult spot, and this is ours. The people who live and work nearby mostly have learned to live with people sprawled on the 400 West median, the regular appearance of police lights, the jaywalking, the occasional broken glass, and the behavioral quirks — staring, staggering, shouting, hunching, muttering, frequent peripheral glances, and the ability to sit perfectly motionless on a bench for a really, really long time — that, in sum, make a lot of Utahns brace for something weird and probably bad to happen here.

It's pretty tame compared to what we'd find in many cities. But I have to admit, it's hard to know what to do with myself when someone who is howling "All You Need Is Love" walks out of the Sacred Space, stops 18 inches in front of my face and tells me I look like John Denver.

This, of course, isn't a security problem. It only gives me a sense of the vulnerability that comes with staying out here. That vulnerability may be part of why crime seems like a pretty big deal at Occupy SLC.

The group came up with a security patrol, but that fell through when various campers complained it was like "the gestapo," said a volunteer guard who goes by Hawaii.

Now Hawaii is trying to figure out alternatives. He's planning a de-escalation seminar and developing a mediation team. Coming from one of the willowy hippies here, words like "de-escalation seminar" and "mediation team" might not be taken seriously. But Hawaii is one of those stout, rectangle-shaped men who can de-escalate stuff using only their eyes. And, he said, heavy-handed protection is almost never necessary.

"I play more Dr. Phil than I do actual security," he said.

The worst of it came a few days ago, when a man urinated on a tent and then tried to stab Hawaii with one of the tent stakes, he said. That was unusual.

The group also is looking at tent layout as a way to keep a better eye on the village, said Occupant Jesse Fruhwirth. The tallest tents are at the outside, campers have tried to create sight lines from all directions, and everyone is encouraged to keep their doors facing the same way.

"It's ongoing city planning," he said.

He said nonviolent examples and norms also have created positive peer pressure.

"We do the best we can to remind people what the laws of the park are, but we don't have any authority as law enforcement. So we're in this zone where all we have is our peaceful means," he said. "In three weeks, we haven't had a crime here that's newsworthy, and that's a pretty good run for Pioneer Park."