This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Little has happened in the quest to determine more precisely what caused the Crandall Canyon Mine disaster, leaving many loved ones of the nine miners who died nearly four years ago wondering whether justice will ever be served.

Their doubts are fueled by the fact that three years have passed since the federal Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) released its investigatory report on the disaster, which began on Aug. 6, 2007.

The report blasted Murray Energy Corp., whose Utah subsidiary ran the mine, for recklessly disregarding safety in pursuing a mining plan "destined to fail" and fined the company $1.34 million for violations contributing directly to the massive Aug. 6 implosion that killed the first six miners (three rescuers died in a second implosion 10 days later).

But the company cannot even respond to MSHA's allegations because the U.S. Attorney's Office for Utah is quietly conducting a criminal investigation at the behest of MSHA and Rep. George Miller, D-Calif.

That criminal probe halted all legal discovery into the substance of the citations, delaying an administrative process that usually gets closer to the truth as attorneys on both sides zero in on pertinent details. It's a proceeding, though, that often relies heavily on human memory, something known to falter over time.

The prolonged probe also is a heavy weight hanging over Laine Adair, who was general manager of Crandall Canyon and Murray Energy's other Utah mines. Miller singled him out for criminal review, questioning whether Adair "individually or in conspiracy with others, willfully concealed or covered up [or made] false representations" to MSHA about dangerous conditions in the mine before the walls blew in.

Those others could be Adair's managers at Crandall Canyon or his superiors with Ohio-based Murray Energy, on up to the boss, Robert Murray.

Adair and his Washington, D.C., attorney, Gregory Poe, declined to comment, citing the ongoing criminal investigation. Murray Energy spokesman Rob Murray also had no comment.

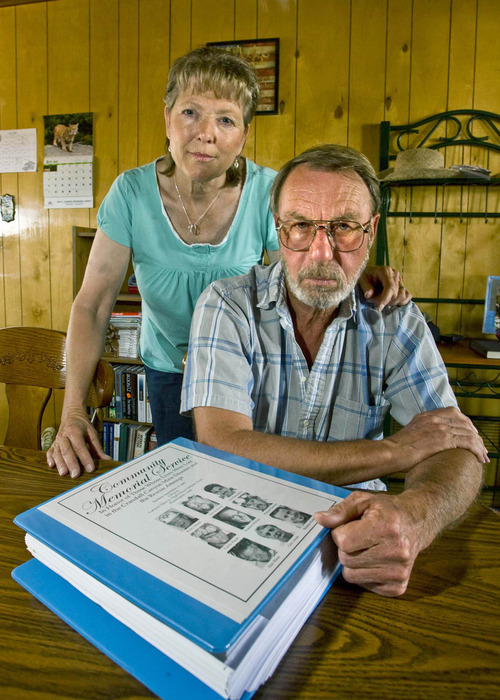

For Frank Allred, whose brother Kerry died in the initial implosion, the longer that questions of responsibility for the disaster linger, the greater his dread that they will just fade away unresolved.

"I don't understand all the legal stuff," the Price resident admitted. "But, yes, it bothers me. It's very frustrating and very sad that this kind of stuff has to go on.

"Everyone wants to get on the bandwagon when it happens. As long as it's a popular thing to do; they showboat," Allred said. "But in the end, what gets done? Nothing. I've given up hope. I don't know how many others have."

Arturo Sanchez lost his dad, Manny, in the initial implosion. Like Allred, he feels "like the longer it goes, the less that's going to get done."

—

Discouraged, but not out of hope • Other victims' relatives may not yet be without hope but they are discouraged, said Ed Havas, a Salt Lake City attorney who helped represent heirs of the first six victims and two injured rescuers in a civil wrongful death and injury lawsuit against Murray Energy and Crandall Canyon's other owners. That suit was settled for a large but undisclosed amount of money in May 2009.

"It is a source of some frustration that it is taking a long time to come to an end. … There's still an aspect of this tragedy left unfinished," Havas said, adding that clients have told him that "though they wish the process had not taken this much time, they are concerned that the process be done well more than it be done quickly.

"They are concerned that if anything does come from the criminal probe, those truly responsible will be called to account [for their actions], and that responsibility not be avoided or placed on a scapegoat just to get a result," he added.

That's the goal of the U.S. Attorney's Office of Utah as well, said its spokeswoman, Melodie Rydalch.

"Even though we received referrals from other agencies on the Crandall Canyon matter, we must conduct our own investigation," she said. "Working with the agents assigned to the case, we must look at things independently before we bring criminal charges. These investigations can, and often do, take a substantial amount of time."

Rydalch acknowledged that her office, which has not had a U.S. attorney since Brett Tolman resigned at the end of 2009, asked MSHA earlier this summer for "what we anticipate will be the final extension of a stay" on the administrative proceedings involving violations cited in the agency's disaster report.

A grand jury has been seated to hear testimony about the criminal case. But Havas and Fred Silvester, a Salt Lake City attorney who represented another group of disaster victims or their survivors, said prosecutors have not contacted any of their clients.

And Lola Jensen, whose husband, Gary, was the MSHA inspector killed Aug. 16 in the ill-fated rescue operation, said she has felt abandoned, receiving only brief responses to her inquiries to the MSHA's victim liaison about where matters stand.

"I get a one-line email back" from the victims' liaison with the U.S. Attorney's Office saying 'the FBI is investigating,' " she said. "I don't know whether to push it [because] we're trying to move on with our lives. Is it my responsibility or someone else's?"

Jensen is convinced that what happened was not merely an accident. If MSHA had been properly informed about how hazardous conditions were in the Crandall Canyon mine, she said, lives would have been saved.

"If there had been some coming forth, at least three others wouldn't have been killed," she said, referring to her late husband and fallen rescuers Dale "Bird" Black and Brandon Kimber. If MSHA had more information about sizable "bounces" that had dislodged big chunks of coal from the mine's walls in the months and days before the deadly implosion, Jensen said, the rescue operation likely would have been conducted differently — and she would not be a widow.

But according to MSHA's disaster investigation, agency officials did not learn until too late about the true extent of a major bounce in March that ended mining operations in a section of the mine about 900 feet from where the deadly implosion occurred five months later. Nor did the company inform MSHA, as it was legally required to do, about a large bounce three days before the fatal collapse.

Those omissions are central to the criminal referrals involving Adair and possibly other Murray Energy officials.

Said Miller in a May 2008 memorandum to members of the House Education and the Workforce Committee: "Adair and others at [Murray Energy] may have purposefully misled MSHA about the severity of the March bump fearing MSHA would close the mine, and [they] continued to adhere to the mischaracterization after the August incidents in an effort to downplay the foreseeability" of the catastrophic failure on Aug. 6.

After Miller made that statement, Adair's attorney Poe called it "deeply disappointing and utterly unjustified," contending "the facts will show that Mr. Adair's conduct was entirely proper."

Adair's alleged actions also figure into the citations later issued in MSHA's investigation. In addition, the report accused the company of violating its approved roof-control plan by removing up to 5 feet of coal from the mine tunnel's floor and hacking into a barrier pillar that was off limits, having been left behind specifically to help hold up the mountain over the mine.

Weakened by these extra cuts, "a sudden and violent failure of the overstressed coal pillars occurred, instantaneously releasing large amounts of accumulated energy," MSHA's probe determined.

—

Memories of event fading • Even if the criminal investigation ended tomorrow and an administrative law judge began hearing arguments immediately on appeals of the 18 citations and orders issued by MSHA, two former agency heads agree the passage of time will make it harder for the process to pinpoint accurately what happened.

Dave Lauriski, a Carbon County native who ran MSHA under President George W. Bush, said "it will be difficult because a lot of things change. The inspector who issued citations may no longer be around. Somebody on the company side might not be around, either. It could go either way."

He feels sorry for Adair, a member of a mine rescue team involved in an unsuccessful effort led by Lauriski to save the 27 victims of the 1984 Wilberg mine disaster, which, like Crandall Canyon, was in Emery County.

"With a strict liability statute like MSHA's, you're guilty until you're proven innocent," Lauriski said.

Davitt McAteer, who preceded Lauriski as MSHA's boss during the Clinton administration, said "it's a shame, just a damned shame" the U.S. attorney's investigation has dragged on so long.

"Unfortunately, it suggests that in the end, it will peter out. The longer these things go, the more likely they are to be resolved without prosecution. That's an accepted fact in criminal work or civil matters," he said.

While the criminal probe has languished, the whole issue of mine safety has become more contentious.

Lauriski noted that political pressure from Miller and others in Congress drove MSHA to beef up enforcement, enact stiffer penalties for infractions and crack down on mines with poor safety records.

Those tough tactics compelled mining companies to fight back, contesting most if not all citations.

MSHA's online records clearly show that's true, including at Utah mines. Between 2000 and 2011, Utah operators paid 37 percent of the $11.7 million in fines issued by MSHA. From 2007 to the present, that rate dropped to 27 percent.

To Lauriski, this approach detracts from mine safety. "When compliance drives safety, it always takes away from miners' ability to identify and eliminate hazards and mitigate risks," he said.

McAteer supports the more punitive approach against mine operators who shirk safety for the sake of production, otherwise the ultimate sacrifices paid by miners — such as those at Crandall Canyon — are forgotten.

Too often, he said, "the poor men and women who work in the mines don't see the improvements that should come as a result of a disaster. That's been the history of mine disasters and miners' lives lost in this country."

Twitter: @sltribmikeg