This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Boeing. Hill Air Force Base. Oxford and Harvard universities. American Aerospace Advisors. QSI Corp.

The commonality? They've all hired or been started by former Utah State University students who created experiments that flew aboard the space shuttle or International Space Station.

But as the expected Friday launch of Atlantis will mark the end of NASA's space shuttle program, the opportunity to send student experiments into space will be severely limited.

For Troy Munro, who just finished his undergraduate degree at USU and will enter a master's program focusing on mechanical and aerospace engineering, that likely means a change in his academic pursuits. During his undergraduate work, Munro studied the effects of boiling various substances as a means of releasing heat while in microgravity environments. USU previously sent up a boiling experiment on an earlier shuttle mission. Munro was also involved with a group of students who were able to go on NASA's zero-gravity plane, commonly called the Vomit Comet, to test the experiment in 30-second bursts.

"I'm going to have to switch. Rather than studying boiling, I'll have to study some kind of energy field I can do experiments on the Earth," Munro said.

Ryan Martineau, an incoming junior studying mechanical and aerospace engineering, also worked on the boiling experiment and rode aboard the Vomit Comet. The plane flies in high arcs, and for 30 seconds everything inside the plane floats. After making several arcs, researchers get a total of about 15 minutes of weightlessness.

"It just isn't the same as being in space," Martineau said. "We can get close to the effects for our short-term research, but to get into space, our group would have to look elsewhere."

NASA still could launch rockets carrying experiments that don't need a person to conduct them, but space on those can be extremely limited. Private companies are willing to take payloads into space on private rockets, but the costs for reaching the stars are indeed astronomical.

To place an experiment on the shuttle, the cost was about $50,000 per kilogram. NASA would fill 50-gallon drums with student experiments to use essentially as ballast. The government would cover nearly all the costs. But after the explosion of the Columbia space shuttle in 2003, NASA canceled the program. Private companies charge between $10,000 and $15,000 per kilogram, said Martineau, meaning the experiment he and Munro took to Johnson Space Center in Houston for its flight aboard the Vomit Comet would have cost between $1 million and $1.5 million.

NASA is committed to continuing its program to send student experiments into space on future U.S. spacecraft and current international spacecraft, said NASA Deputy Administrator Lori Garver during an Internet broadcast June 28 in which she answered questions from Twitter users.

"We will continue to send student experiments in space. It's been done since the beginning, and it's absolutely critical that we continue to involve students in this program," she said. "With new transportation modes, cargo programs with commercial companies will carry student payloads into space, and we'll continue with our international partners to do the same."

But if a government-subsidized program isn't ready to go for several years, that means the likelihood of sending an experiment into orbit or onboard the International Space Station is nearly nonexistent.

For Mike Wirthlin, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Brigham Young University, that may mean he won't be able to continue working with Sandia National Laboratory in New Mexico to create circuits that resist the damage caused by radiation.

Sandia may have to resort to using military rocket launches to get their experiments into space, and it may be impossible to obtain clearance for Wirthlin and his students because of the amount of bureaucratic red tape and necessary security clearances.

"There are opportunities, but they are not as flexible and not as convenient as the space shuttle was," Wirthlin said.

It's a situation that leaders at USU — the school that has sent more experiments into space than any other university — are sadden to see.

"The bottom line is that the kind of programs we've been used to doing require regular access to space flight," said Jan Sojka, head of the USU physics department. "For four years, if there's no opportunity to put an experiment in space, that will be a damper to build something that you never see fly."

But he touts the small cubesats that USU has been creating and planning to launch soon. Most satellites are the size of a Volkswagen Beetle, but these newly designed nanosatellites are about the size of a Rubik's Cube.

Launching one of those costs about $40,000 aboard a NASA rocket, and a team of students and researchers hope to launch one this fall. With that expense, it means students will be more closely supervised while making a cubesat because Sojka, and others who find funding for a launch, would hate to put it up into space and have it fail.

Sojka is also hopeful that students will one day soon have options to send experiments back into space.

"There is a future, but it all comes back to what vehicles are available and who is providing this launch capability," he said.

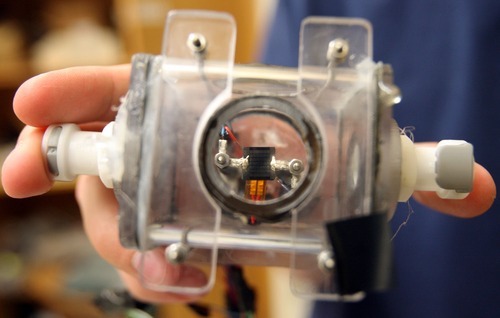

J.R. Dennison, a USU physics professor, had an experiment launch in 2008 and it spent about 18 months on the International Space Station. He and several students designed an experiment that placed several types of material on the outside of the space station to see how they held up against the rigors of space, such as atomic oxygen and charged particles in solar wind.

A former alumnus of USU, David Yoel, is the president and founder of American Aerospace Advisers. He was able to work out a deal with private company Space Adventures, which sends up private citizens who pay millions of dollars to be a space tourist, to have the company take up and perform experiments ranging from simple to complex.

Space Adventures has yet to have a space tourist take up an experiment, but Dennison hopes it happens soon.

While NASA figures out its next steps, Dennison said he has faith in his students' abilities to find a way to the heavens.

"These kids are so creative and motivated that they're going to figure something out. They're smarter than we are," he said. "I don't know what they're going to figure out, but they're going to figure it out. They're not going to let it go."

smcfarland@sltrib.comTwitter: @sheena5427 —

NASA spinoffs

The space shuttle program has led to more than 100 technology spinoffs resulting in new products on Earth. Some of those include:

A new artificial heart pump being tested in Europe

Insulation in NASCAR vehicles that protects drivers from the engine's heat

A compact instrument that analyzes blood in 30 seconds instead of 20 minutes

Infrared cameras that can scan for fires

An exploder that uses rocket fuel to detonate land mines safely

A hand-held device that can extricate people from crunched cars without a power source

Source: NASA