This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Many Utahns know or resemble a family like the Scheffners.

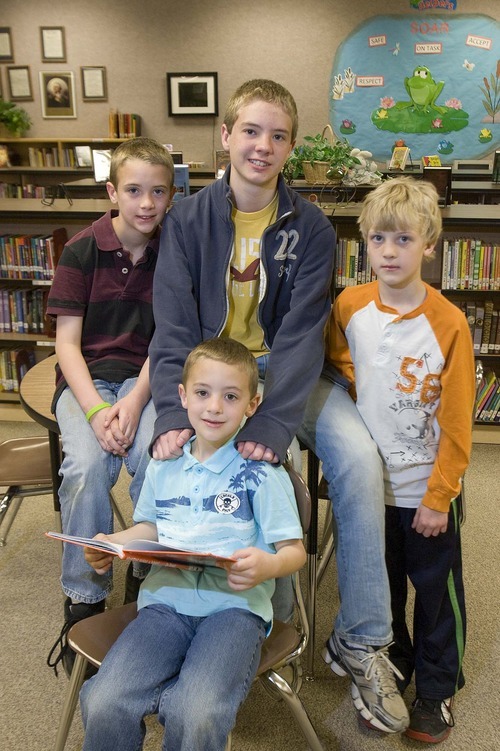

Gary and Jennifer Scheff-ner have lived in Utah all their lives and now reside in the popular suburb of Sandy. They live in a four-bedroom house and have four children. She's active in their schools' PTAs, and he's on a school community council.

Many Utahns, according to polls, also share the Scheff-ners' views on education funding: They'd like to see schools get more money, especially to reduce class sizes.

"I personally am amazed with what teachers are able to do with the funding," said Jennifer Scheffner, whose four boys attend schools in the Canyons district. "These class sizes are huge, and they're able to accomplish so much. It also makes me wonder how much more they could accomplish if they didn't have such large class sizes, if there were more resources available."

In Utah — a state with a high proportion of children and the lowest base per-pupil spending in the nation — school funding is a perpetual concern. But it's often misunderstood. Utah's system for funding schools is a complex web of programs, formulas and terminology that can make it difficult for average Utahns to understand exactly how their tax dollars pay for education.

Most Utahns have heard that the state has the lowest base per-pupil spending in the nation, largely because of its high proportion of children and large amounts of public land. But what to do about that situation, how it affects classrooms and whether it can be overcome is less clear.

"It's terribly complex," Sen. Lyle Hillyard, R-Logan, Senate budget chairman, said of school funding in Utah. "The way it is now, you look at a budget and you have a hard time, unless you really study it, understanding where the money is going and how it compares to where it ought to be going."

The Scheffners are happy about many of the things their children's schools offer: technology, music programs and an achievement coach who was hired in the elementary school to bolster academics.

But Gary Scheffner said he wishes Utah schools had more money to deal with such issues as class size.

"A lot of people would maybe even be willing to pay more taxes to get it up a little higher," he said, "especially if they know that's where it would go."

—

The class-size conundrum • It's an issue that affects classrooms statewide, including those of the Scheffner children. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, Utah had the highest student-to-teacher ratio in the nation — 23.7 students per teacher — in 2008-09, the most recent data available.

The Scheffners' oldest son, seventh-grader Ben, is one of 31 students in his sewing class at Indian Hills Middle School.

To handle the challenge of instructing so many students at once, his teacher, Connie Mayer, only teaches half the class how to use sewing machines at one time. The other half crochets until their turn.

"It's night and day for teachers," Mayer said of the difference between larger and smaller classes. "I feel there should be 20 to 25 max in a classroom, especially when it's a lab situation."

Twenty-eight students fill Sam Scheffner's fourth-grade classroom at Sunrise Elementary.

On a recent day, teacher Tamra Fuhriman moved from student to student as they arranged words written on colored strips of paper into different categories as part of a spelling lesson.

Fuhriman is grateful for the many things Sunrise has that other schools might not: enough textbooks, desks and technology such as a document projector that she says she uses daily. But she says class sizes make a big impact.

"Last year, I had a class of 24 and it was great," Fuhriman said. "Some people think, 'What's one or two kids?' It makes all the difference."

When districts face budget shortfalls, as many did this year, they sometimes raise class sizes to deal with that. Canyons chose not to raise class sizes this school year, instead opting to implement furlough days as one way to handle a projected $13 million shortfall.

Keith Bradford, Canyons chief financial officer, said it's not so easy to lower class sizes. It's an issue for many districts.

"If we decreased class sizes by one, it would cost us $2.2 million," Bradford said. "You're talking about a huge amount of money in a time we're being cut."

—

Will Utah always be last? • Many Utahns say they'd like to see more money for schools, but some budget experts say it's unlikely the state will ever be able to move up from its last-in-the-nation per pupil funding status.

"It's not ever going to be overcome unless somehow we double the money," said Michael Kjar, policy and budget analyst with the Governor's Office of Planning and Budget. "It's really an issue of how much do the citizens of Utah want to tax themselves."

Hillyard said Utah's population is growing so rapidly compared with many states that "we'll never catch up."

"I see raising taxes right now as being counterproductive to what the governor is pushing with economic development," Hillyard said, noting that improving the economy will result in more tax revenue.

Others, however, say the funding situation could be improved by changing Utah's tax structure.

"The changes we've witnessed over the last 10 years have reduced our funding dramatically," said Sharon Gallagher-Fishbaugh, Utah Education Association president.

Stephen Kroes, president of the Utah Foundation, said property tax reductions, implementation of the flat tax, and a constitutional amendment passed in 1996 that allowed higher education to share income tax revenue with public education have "done more to reduce the education funding effort over 15 or 16 years than anything."

Utah, which once ranked among the top 10 states in the nation for proportion of personal income going toward education, ranked 25th in 2008, Kroes said.

Some Utahns have also been critical of the state's child tax credits, which they say keep Utah's largest families from paying their fair share into the system, though Kroes said such credits are common throughout the nation.

Pam Perlich, a senior research economist at the University of Utah, said that when it comes to school funding, there's definitely room for improvement.

"It's a matter of public policy and community priority," Perlich said. "As households, we afford lots of things. One could question whether all the things we consider necessities are really more necessary than public education."

She said as time passes and the state becomes more diverse, that relatively low funding will affect achievement more.

"We don't have a homogenous population and we don't have stay-at-home moms, so the old model is broken," Perlich said. "More and more, students will not be able to succeed with the lower funding because schools delivering the same kind of curriculum won't be able to reach them."

The Scheffners said they don't believe more money alone can improve education. Jennifer Scheffner said money must be spent wisely and parents need to do their part to help their children and schools.

But they said they would be willing to pay higher taxes for schools.

Many Utahns feel the same way. Sixty-nine percent of Utahns surveyed in a recent poll conducted by Dan Jones and Associates for the University of Utah's Center for Public Policy & Administration and the Exoro Group said they would "probably" or "definitely" be willing to pay more in taxes to reduce class sizes.

But the Scheffners feel that their district generally makes good decisions with the funding it does get.

"There's always room for improvement," Jennifer Scheffner said, "but, overall, I'd say we do very well with what we have."

School funding: How one district makes it work

Here's an example of where the Canyons School District got— and spent— its money last school year: