This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Salt Lake City teacher Tim Bailey was sitting in the White House Rose Garden nearly a decade ago when President George W. Bush gave an early speech about No Child Left Behind.

Bailey immediately had concerns about the education law. He worried because it didn't take individual student progress into account. And it expected 100 percent of students to reach proficiency in math and reading by 2014.

"I had great trepidation over No Child Left Behind [NCLB]," said Bailey, who was at the White House because he was Utah Teacher of the Year. "If you were trying to get rid of public education, some might see this as a way of proving it doesn't work, if you don't meet those goals."

Now, nearly a decade later, with students far from that 100 percent goal, President Barack Obama's administration is gearing up to change the law dramatically.

Obama wants to take student progress into account when measuring school success. His plan would reward high-poverty schools and districts that show improvement, but it would also require states and districts to identify and intervene in schools that persistently fail to close achievement gaps. The lowest-performing 5 percent of schools in each state would be required to implement one of four turnaround models — which, in some ways, may be more severe than current sanctions that struggling schools face under NCLB.

And the law's new goal would be to make sure students leave high school ready for college and careers.

Obama laid out the plan in a 41-page blueprint released last year. The president has called on Congress to fix the law, also known as the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, before the start of next school year. Some have called that timeline overly ambitious.

The U.S. Department of Education has estimated that, under the current law, 82 percent of America's schools could fail to meet NCLB goals this year. In Utah, more than 20 percent of schools failed to meet goals under NCLB last year, and it's likely that percentage could rise as the goals get loftier.

"I think what the [U.S.] Department of Education is hearing is there isn't anybody that can be perfect," said Brenda Hales, Utah associate superintendent. "You have a certain amount of kids where what you have to do is concentrate on making their life better and challenging them and expecting a whole lot ... but it's not reasonable to expect 100 percent."

—

Setting goals • State leaders, however, aren't waiting for the reauthorization of NCLB to chart Utah's educational course. Many of the goals adopted by state leaders in recent months aren't that far off from what Obama is proposing for the nation as a whole.

The Governor's Education Excellence Commission recently adopted a goal that two-thirds of Utahns earn postsecondary certificates or degrees by 2020. The commission would also like to see 90 percent of third-graders proficient in reading and 90 percent of sixth-graders proficient in math. The state Board of Education has been discussing similar goals.

A number of Utah groups have joined together to support a Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce initiative called Prosperity 2020, which also has the two-thirds goal and aims to see 90 percent of Utah students achieve proficiency in reading and math by the end of elementary school by 2020.

"Ninety percent is still a challenging goal, but it's more realistic," Hales said. "It will make everybody stretch in the system."

Hales said it's not that Utah has abandoned the 100 percent goal of NCLB but rather that the state is working toward both sets of goals. Utah will also soon start assigning schools letter grades based on students' proficiency and progress in a number of subjects, graduation rates and measures of college and career readiness.

Hales called the blueprint for rewriting NCLB "a good starting place because it allows us to have discussions about what we want to keep, what was good about No Child Left Behind."

For example, many educators praise NCLB for forcing schools and teachers to dig deep into student performance data and focus on struggling groups of students.

But many educators have decried the law's expectation that every student achieve reading and math proficiency by 2014. And they say NCLB's system for judging schools can be demoralizing. In order for a school to meet yearly goals, each student group within a school — grouped by ethnicity, income and ability — must meet goals. If one group fails to meet a goal, the whole school is deemed as having failed to make Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP).

"I'm not sure I've ever been enamored with that system because I think that there's a lot of really good things going on in the schools," said Dale Wilkinson, principal at Odyssey Elementary in Ogden. "I know in our school district, there are just incredible things going on, even in schools struggling to make AYP."

Odyssey received a federal grant last year intended to help the struggling school improve. The grant required the school to choose one of four reform models: replace the principal and half the teachers; convert the school to a charter; close it; or replace long-serving principals, improve the school through curriculum reform, training for educators, extended learning time and other strategies. Odyssey, along with 10 other Utah schools receiving the grant, chose the fourth option.

If Obama's proposals become law, more struggling schools would likely be asked to choose among those four options.

—

Mixed feelings • Many Utah educators are pleased with the prospect of NCLB undergoing major editing. But those who have looked at Obama's proposals also say they are no panacea.

Jacque Conkling, a U.S. government teacher at Highland High, said she's skeptical of making low performing schools choose from among the four reform models. When Conkling's last school, Glendale Middle, received one of the grants last year, she decided to leave.

She said reform efforts should be focused on improving student attendance, lowering class sizes, increasing access to technology and improving teacher pay.

"[Teachers] need to be given credit in a positive way, instead of always being told how much better they can do," said Conkling, who taught at Glendale for 15 years, noting the socioeconomic challenges many schools face.

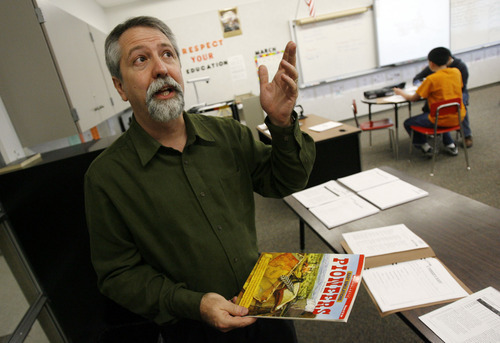

Bailey, the teacher who sat in the Rose Garden during the NCLB speech, has mixed feelings about Obama's proposals. When Obama released the blueprint last year, federal education officials asked Bailey for his feedback after hearing him speak when he was named National History Teacher of the Year in 2009 by The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Bailey, who now teaches U.S. history at Northwest Middle School in Salt Lake City, responded with a five-page analysis of pros and cons. For example, he likes that the plan focuses on college and career readiness and would measure students' academic progress.

Under cons, he listed the proposal's emphasis on performance pay for teachers, saying it can be a difficult thing to execute especially when comparing teachers of different subjects. He also wondered why schools must be labeled as "reward schools" or "challenge schools," saying that seems to create winners and losers.

"In some ways I think it's much better," Bailey said of Obama's proposal to overhaul NCLB. "Do I think that it's where it should be? No. I think there are things that could be changed."

See the proposals

To see President Barack Obama's blueprint for changing No Child Left Behind go to http://tinyurl.com/yzhkddy. Or to see a fact sheet on the proposal, go to http://tinyurl.com/3kcpnpg.