This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2010, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The haloed silhouette, on a black flag honoring American military members who are missing in action, stands watch on a small balcony overlooking the interstate. Next to the flag is a coffee can, brimming with cigarettes that have been sucked down to the filter.

Neighbors say they often see the soldier who lives here standing on the terrace, staring east over the rugged Wasatch Mountains. Sometimes, they say, he'll wave to them, but he rarely comes down the steps.

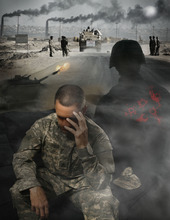

That seems understandable to anyone who has heard his story. Inside his dark and cluttered apartment, he speaks in gruesome detail about a terrible night in the summer of 2005 in the northern Iraqi city of Tal Afar, where a foot patrol of frightened soldiers crept warily through an area crawling with insurgent snipers.

"I heard the bullet whiz past me," he says. "I turned around and saw my friend grab his throat and fall to the ground. I tried to stop the bleeding, but there was nothing I could do. There was just so much blood. I pulled off his night vision goggles, and there was this look of fear in his eyes."

And with that, the soldier says, his best friend was dead.

He has told this story to doctors, counselors, family and friends. It explains better than he could why he has struggled to adjust to life after Iraq.

Except for one thing: It does not appear to be factual. No American military member died in Tal Afar on June 7, 2005. Those who were killed in that volatile city around that time were Marines, not soldiers. Other details simply don't add up.

Under rules imposed this year, veterans no longer have to provide absolute proof of the trauma they experienced in order to receive compensation for post-traumatic stress. Now, just being able to prove they were at war is generally enough. Some fear that is opening the door to fraud. But as the Department of Veterans Affairs attempts to sort the malingerers from the mentally ill, those whose wartime memories have been twisted by time and pain could get caught in the middle.

—

Invisible wounds • Post-traumatic stress disorder touches everyone differently. Some people exposed to the most extreme horrors of war will be psychologically unscathed. Others, who have experienced minimal trauma, may suffer a lifetime of sleeplessness, anxiety and hyper-vigilance. That makes it all too easy to miss those who need help — and all too hard to spot those who are faking it for want of a benefits check.

"Post-traumatic stress is a bit of a sloppy diagnosis, because it basically comes on the basis of self-reporting, as opposed to being able to actually do a lab study," said Duke University psychiatrist Dan Blazer, who co-authored a 2002 study on the connections between post-traumatic stress and other mental health disorders. "In that sense, people can potentially game the system, and they probably do."

Nonetheless, figuring it better to let a few goldbrickers slip through than to exclude those who need help but can't conclusively link their symptoms to their experiences in uniform, Congress and the White House have pushed the Department of Veterans Affairs to settle claims for financial compensation quickly and liberally.

Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, which advocates on behalf of military members and veterans of the nation's ongoing wars, lobbied for several years for the change.

"While the disability claims system overall remains ill-equipped and outdated, this is a step in the right direction," said the group's executive director, Paul Reickhoff. "This change removes a key bureaucratic obstacle to care and will go a long way toward helping men and women coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan with invisible wounds."

But Utah Department of Veterans Affairs Director Terry Schow fears the new rules might encourage fraudulent claims.

"They've liberalized it — and I think it's a credit of the secretary of Veterans Affairs that he recognized that folks were having to jump through all sorts of hoops to get help," Schow said. "But now what they're saying is, 'Just go ahead and pay up, then we'll find out later,' and that could be a recipe for all kinds of problems."

Schow — himself a veteran of the Vietnam War — said that he would happily compare the integrity of those who have served in uniform to any other group in America. "But sadly," he said, "this is a money-driven world, and money drives people."

—

Tracing tangled memories • A single fraudulent claim can cost the government millions of dollars over a veteran's lifetime. So VA officials say they will zealously pursue fakers — a system they call "pay and chase."

But caught in the middle of that chase may be veterans who are haunted by memories of traumatic experiences, which aren't, strictly speaking, true. No one knows how large this group is, but some of those who work with veterans say it's undoubtedly a much larger number of vets than those who are simply liars in pursuit of glory and money.

Some, like the soldier afflicted by his recollection of the best friend who died in his arms, are likely genuine victims of post-traumatic stress. VA officials in Salt Lake City say he's a bona fide veteran of the war in Iraq. Counselors also say they don't doubt the sincerity of his symptoms.

(The Salt Lake Tribune is not identifying the soldier, who could risk losing medical and mental-health care if benefits officials conclude that he has falsified stories about his service.)

So why doesn't his story add up? Loren Pankratz, a psychiatrist who spent 25 years working with Vietnam War veterans at the VA hospital in Portland, Ore., said there's no single answer that explains every person's conscious or subconscious motives for telling non-factual stories.

"People change and, over time, you might become an entirely different person than you were when you went to war," said Pankratz, author of the book Patients Who Deceive. "What can happen is that people will weave new metaphors into their belief system that support their developing ideas about the war and their experiences in it."

Others may be motivated to dissemble by shame, Pankratz said, "and maybe some just want to be more macho than they really were. ... Everybody colors their own memories a little. And if you start going over it, again and again, some people do start believing those things."

Still others may be victims of the psychotherapy process, which under some circumstances can provide moral and emotional "rewards" to vulnerable patients who unveil deeply kept secrets — even if those revelations aren't factual. Pankratz said that group therapy — a popular model for veterans, in which patients are inundated by the stories of others — can be a particularly rich environment for creating muddled memories.

"These false memories, they basically grow in the context of therapy," he said.

Whatever the motive or cause, research suggests the phenomenon could be widespread. In a 1997 study of men and women who served in the 1991 Gulf War, psychiatrists at the VA Medical Center in West Haven, Conn., found that nearly 90 percent of veterans had their memories of traumatic wartime events change. Two years after coming home, more than two-thirds reported traumatic memories that they had not mentioned when they first returned.

Over time, the researchers found, veterans were more likely to report having experienced an extreme threat to personal safety, being stationed close to enemy lines, witnessing the disfigurement of human casualties and seeing others killed.

—

'It wouldn't be war without killing' • Veterans also can have their memories sculpted by others' expectations, said writer and former Army officer Roman Skaskiw, who served tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Whenever he returned home, Skaskiw sensed that those who hadn't shared his experiences only wanted to know about the violence he encountered.

"I'm not sure that's such a horrible thing," he said, noting that it's important that civilians don't just get a sanitized version of the brutalities of combat. "It wouldn't be war without killing."

At the same time, he said, the questions were often difficult to answer. "A lot of people wanted to know if I killed someone," said Skaskiw, who writes at http://www.romanskaskiw.com and is working on a memoir. "That was annoying."

It was clear which experiences people most valued.

"This reverence that veterans get is something that is very real," he said. "And whether they're aware of chasing that reverence or not, many veterans make moves to capture it."

Understanding that war memories can be fluid, some come to question their own stories.

James Holbrook, a Vietnam veteran who lectures at the University of Utah's S.J. Quinney College of Law, recalls with great detail the day he stepped off an air-conditioned airplane and into "a wall of heat and smell in Saigon."

As he walked off the plane, Holbrook recalled, he passed a line of "hollow-eyed grunts who had survived 365 days in the meat grinder."

One of them looked up at Holbrook and said, "Hasta la vista, shitbird."

At least, that's how Holbrook remembers it. That's the truth, as he knew it. But, he acknowledges, he can't be certain that what he remembers about that day in January 1969 is what really happened — even though he says he's never felt any desire to embellish his story.

What Holbrook does know — without a doubt, he said — was "the recognition that I had fallen into the rabbit hole, and I wasn't going to get out for a long time."

But were the men he passed really "hollow-eyed grunts"? Did someone really call him a "shitbird"?

"I'm not sure that is a memory or a reconstructed memory," Holbrook said. "I know it reflects how I felt, because I was so scared."

Holbrook said that as he began trying to write about his experiences in Vietnam, decades after the war, he came to the realization that there was a difference between "literal truth" and "meaningful truth."

"I couldn't really trust my memory to be like a videotape," he said. "But I needed to write about my experiences, so instead of trying to censor what was true, I wrote what I thought was meaningful."

—

A dangerous path • Blazer, the Duke University psychiatrist, said distinguishing between "truth" and "fact" might not be all that important for providing compassionate care for suffering veterans.

"It doesn't help us so much to say, 'Well, let me go back and find out what really happened,' " Blazer said. "Because what really happened on the battlefield might actually be a few steps removed from a patient's suffering."

Blazer said he understands the VA's need to identify fraud. But as the bureaucracy begins to deal with its policy change, he said, it must be wary not to make victims of those who are simply expressing the truth as they know it.

"We have to be very careful if we actually are accusing people of not remembering things correctly or faking symptoms," he said. "That can lead us down a pathway that can potentially be very dangerous because we don't want to be denying care to individuals who are really suffering. I'd much rather err on the side of being inclusive."

Help for veterans

Mental health resources at the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Hospital

11 a.m. Tuesday • Free no-appointment mental health examination clinic. (Veterans should bring a copy of their DD-214 discharge form.) For more info, call 801-584-1255.

Online • suicidepreventionlifeline.org/Veterans/

Combat Veteran Call Center • Staffed by combat veterans 24 hours a day, 877-WAR VETS (877-927-8387).

Vet Center • For confidential readjustment counseling, vetcenter.va.gov. —

An obvious forgery

Utah Department of Veterans Affairs Director Terry Schow knows of many veterans who have made false claims about their service in search of attention and compensation.

And sometimes, Schow said, untruthful claimants had other aims.

He recalled one recent case in which a man who had been accused of child abuse tried to mount a defense based on post-traumatic stress, providing as evidence a discharge document that was clearly forged.

"It said he had received a Silver Star," Schow said. "And it was signed by a General Abrams."

Creighton Williams Abrams was chief of staff of the Army during the waning years of the Vietnam War. He had three sons, all generals. "And, you know, general officers don't generally go around signing discharge papers," Schow said.

But the kicker, Schow said, was that the form was submitted in 14-point type, which is much larger than the typeface usually used by the military.

"That one was easy to catch," Schow said. "Not everyone makes it so simple."