This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Sam Weller haunted his spouse before he ever left this corporeal realm. In fact, it was dread at first sight.

When Lila, the bibliophile, was introduced to Sam, the salesman, "He was an apparition," she says. "He'd been cutting open a wall and he was covered with plaster dust from head to foot."

Sam also had a ghoulish habit of making things — namely, the books Lila was reading — disappear. She bridles at the memory of Neil Morgan's "Westward Tilt," which she thoroughly enjoyed until Sam sold her copy.

"Well, he had immense respect for your opinion," their son, Tony, consoles Lila. "If you said it was good, then he could put his heart behind it."

Her indignation is in jest, of course. Lila and Sam Weller were together for 60 years, both as a couple and as co-workers, and the only matter related to Sam that truly spooks her is the eerie quiet in her exuberant husband's wake.

Lila may be most youthful 98-year-old on our planet. She has clear eyes, smooth cheeks and a sharp mind, and she chides herself when she can't remember minute details from decades past.

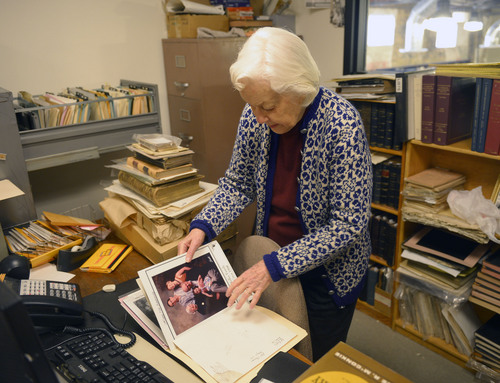

She still works three days a week at Weller Book Works, collating rare books and identifying the people in old photos — which fill a file cabinet in a back room. When she's done with a book she initials it "LN," as she has since Lila (nee Nelson) met Sam at the midpoint of the 20th century.

Their tale has an appropriate storybook flavor.

In 1949, the roommate with whom Lila split her rent was marrying and moving out, and when Lila accompanied an unhappy-in-love friend to a fortune teller, she was asked if she had any questions. She had just one: "Am I going to find a place to live?"

The fortune teller knew a woman who needed a roommate and was thus uniquely qualified to divine the answer. (Yes.) Nelson and the fortune teller's friend met at Owl Drug on 2nd and Main and hashed it out over a Coke, and when Lila moved in, the roomie took note of her affinity for books — "I'm the kind of person that reads the stuff on the cereal box," she says — and told her she simply had to meet a man she knew who owned a local bookstore.

So one night, wearing just Levis and T-shirts (scandalously casual for a woman at night, she recalls), they went to meet the man her roommate knew — Sam Weller — at Zion Bookstore.

In the days that followed, a presumably less demonic Sam took Lila to her first baseball game, and she began to pitch in more and more at the store.

"He was not the best bookkeeper," she says. "I guess after two or three years of helping him with his bookkeeping, he decided I was useful, and he decided to marry me."

Sam would later joke that he'd tried to get acquainted with her so she'd be a return customer, but then she wound up reading his books for free.

"I don't think Sam Weller's would have become what it is without Lila Weller," says Catherine Weller, their daughter-in-law and current co-owner of Weller Book Works at Trolley Square, located at 665 E. 600 South. "Sam was an excellent bookseller, but she took care of the back end. She was the glue that held Sam Weller's together."

It was Lila who named it Sam Weller's. First it had been Zion Bookstore because Sam's father Gustav had wanted a good Mormon name, she says, and Deseret was already taken. Then Sam had named it Weller's Bookstore. But she convinced him that Sam Weller was "a perfectly literary name" — given the character in Dickens' breakthrough "Pickwick Papers" — and a fair bit catchier.

She also established a cutting-edge inventory system. They'd put a slip in each book and have a card at the desk in the back, and as they sold a book they'd pull the slip and match it to the card. Few bookstores at the time were so organized.

The selling, she says, she left to Sam. She was quite shy and he was quite ... not.

Once they were eating lunch on a flight to New York and Sam bit into a cherry tomato, propelling the pulp onto the bald spot of a man sitting in front of him. Sam jumped up with his napkin, wiping off the man's head and striking up a conversation.

"The rest of the trip they sat together and talked," she says.

But Sam's health declined in 1983 after he had bypass surgery on an artery in his left leg, and then in 1992 he had four more bypass surgeries. When he lost his vision to a viral infection in 1997, both he and Lila quit the store.

"For being such a livewire all his life, he was very patient after he went blind," she says. "But he just didn't like to be alone, wanted somebody all the time there with him."

And he asked Lila, who once caught him up on the latest bestsellers as they rode to work, to read to him again.

Often he'd close his eyes and she'd try to gently shut her book when he'd cry out "What's the next thing?"

Lila missed Sam Weller's — as did Sam, who would call his son and now-owner Tony three times each day and say simply "Report."

When Sam died in 2009, Lila asked Tony if she could come back to work.

"I had maybe five friends, where [Sam] had a whole city full," she says. "I missed the store, really. I wanted to be where the action was."

They no longer required a bookkeeper, but Tony set her to collating a heap of rare books. Catherine says it's invaluable to share the company of someone who has survived so many struggles — from a fire that gutted their old building, to a radical restructuring of Salt Lake City that decreased foot traffic along Main Street, to the rise of nationwide chain booksellers.

"She's still an active person with an active mind," Catherine says.

It's a comfort knowing, she says, that times are tough for booksellers, but nothing's ever beaten Lila Weller.

Twitter: @matthew_piper