This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

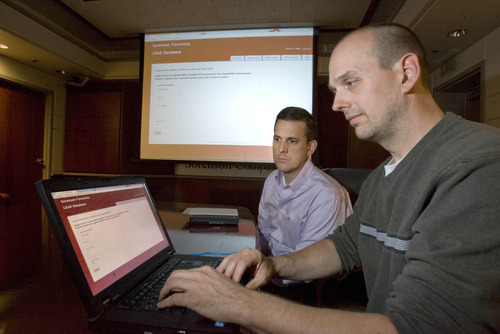

With a few quick clicks, Mark Szczepanski uploads the file from his desktop to a simple, red-and-white web page. A few seconds later, a bar graphic turns green.

If Szczepanski was a police officer, he might have just found a rape suspect.

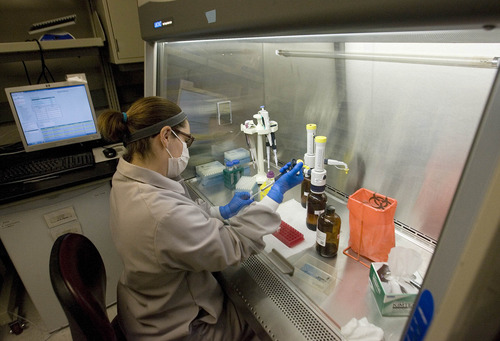

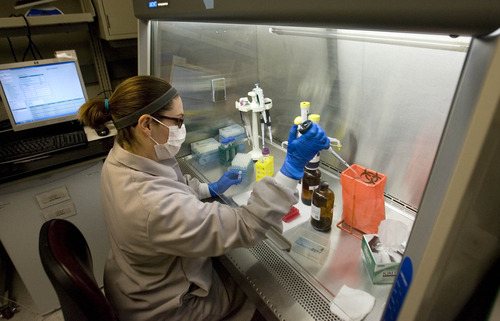

He was using a test version of a new cloud-based DNA database offered by Utah's Sorenson Forensics, a DNA testing company. Simple to use and easy to update, the LEAD (Local Entry Accessible DNA) Database was created for local police departments and almost instantly compares DNA test results — say, a suspect's cheek swab with a semen sample collected at a rape scene.

It has the potential to change the way police use DNA testing, allowing them to access the information more easily and use the technology to investigate more crimes, said Lars Mouritsen, Sorenson Forensics' chief scientific officer.

"It's pretty simple…but incredibly powerful," he said. The product offers a possible solution to state agencies' struggle to keep up with the explosive growth of DNA testing in police work, but concerns privacy advocates who question the security of cloud-based computing and the wisdom of entrusting such sensitive information to a private company.

"How are you ensuring that data would be kept safe?" said Marina Lowe, the legislative counsel for the Salt Lake City chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

—

Explosion of DNA data • Since the firstDNA-based conviction in 1987, the technology has become an essential tool for police all over the country. Scientists can now extract DNA from miniscule collections of cells — even a touch can leave enough evidence.

"DNA, for us, is extremely valuable," said Salt Lake City Police Detective Mike Hamideh, a 17-year veteran who spent eight years in homicide and narcotics. And juries schooled on the long-running hit TV show "CSI" are often looking for such scientific, non-subjective data.

"It's become a standard that investigators are using. The courts are asking for it," Hamideh said.

As the technology allows more DNA collection, laws are also changing to allow investigators to collect samples from more people. In Utah, a state-run database stores DNA information from those convicted of a class A misdemeanor or worse, as well as people arrested for a violent felony with probable cause, said Jay Henry, director of the Utah Department of Public Safety Crime Lab.

"We've got probably almost 85,000 samples in the database," Henry said. The more information a database contains, the more valuable it becomes for police. "What we're seeing is an exponential growth of hits and a real value of these databases to solve crime."

But entering offender information into the database still takes at least a month, and can be as long as six months, Henry said, depending on how much grant money the lab has available.

"If we have the money, we've got the information in the hopper. If not, we get the money in the next grant cycle," he said.

—

Quicker results, faster leads •Sorenson Forensics says their DNA database can help reduce the turnaround time. Instead of relying on state crime labs entering the information into the database, each law enforcement agency could have one or two people authorized to upload profiles, speeding up the process for entering profiles and executing searches.

"There's been a lot of interest because there's a real need," Mouritsen said. Police departments could also use DNA testing in more types of crimes.

"It's sort of up to the agency to decide what goes into the database," Mouritsen said.

The databank doesn't address the cost of DNA testing, which is a large part of the reason police use the technology primarily in crimes like homicide and sexual assault. Each test still costs hundreds of dollars.

"Just to take a DNA sample from a car prowl, that's a significant expense," Hamideh said. "We have to be judicial in the way we use tax money."

Still, Sorenson Forensics hopes that as technology advances and the cost comes down, organizing the data into a form usable by people who don't have years of scientific training will become more important. The price of the service depends on the size of the department, but for a mid-size agency like Salt Lake City, the initial set up would probably be about $10,000, plus about 15 percent of that amount each year for maintenance. No agencies have signed up yet since the product was introduced this month.

"It seems logical that someone should develop this type of product," said Henry, of the state crime lab.

—

What are the safeguards? • But there are potential pitfalls.

One, says the ACLU's Lowe, is the security of cloud-based computing. It's a hot concept for tech companies, and gaining popularity with the masses with applications such as the web-based word processing program GoogleDocs.

"There have already been some concerns about security related to cloud databases in the private sector," said Lowe, whose organization opposes the idea that anyone arrested for a violent felony could be entered into the database, even if they turn out to be innocent. "DNA can reveal all sorts of information, including family history, race, background."

Sorenson Forensics is housing the data on Microsoft servers, said Szczepanski, information systems manager at Sorenson Genomics, parent company of Sorenson Forensics. In addition to being encrypted with an authorized log-on and password, the information isn't stored with any names or identifying information. The database matches, meanwhile, would be used for generating leads rather than being directly admissible in court

State agencies relying on a private company to house such sensitive data is also a potential problem, Lowe said.

"What sort of safeguards are in place on who can access it? Under what circumstances is that information shared?" she said. "There are a whole host of issues that come up in using private companies to help law enforcement in this way."

The proprietary nature of the LEAD database could also be an issue. Utah's state-run database is part of the FBI's nationwide Combined DNA Index System, which allows detectives to compare their suspect DNA with data collected nationally, but agency's private cloud-based database would not be.

"We need [the databases] to talk to each other," Henry said. Though the process might be slower, state lab technicians and the FBI also act as gatekeepers and safeguards for DNA storage, both curating and ensuring the security of that information.

But there is already a flood of DNA information to categorize, and it will only grow as the technology becomes more widely available, cheaper, and in demand in court. In an era of recession-strapped governments, the idea that the state might look to private companies to help make that data more available and usable doesn't seem so far-fetched.

"We're seeing this technological change and it's inevitable," Henry said. "Our policy discussions are behind."

Twitter: @lwhitehurst