This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2012, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The 845 million active monthly users of Facebook, reading the posts of their friends, seeing their photos, likes and comments at near instant speed — that's made possible in great part by a Utah company.

Fusion-io Inc. didn't exactly burst on the computer storage scene back in 2005, but turns out its founders had the right idea, the right technology and the right execution, so much so that today its products are sold by the likes of computer server makers IBM, Dell and Hewlett-Packard, and used by companies such as Apple, Facebook and Salesforce.com.

Fusion-io and its solid-state memory devices are riding fluffy clouds of change in computing in which companies use large banks of servers to deliver data and services at quantities and speeds not possible even a few years ago.

Facebook relies on Fusion-io's products and could not do what it does without the kind of data storage devices that are replacing the stodgy spinning hard-disk drives, said Fusion-io CEO and Chairman David Flynn, who also is a co-founder. The Utah company buys its chips made on silicon wafers from IM Flash Technologies in Lehi.

"We're taking that, packaging that up, putting a controller and software in front of it, and that's what's running Facebook's data center," said Flynn.

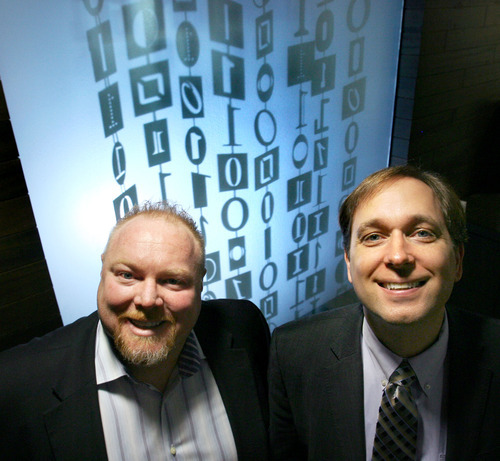

"When you type up your status updates and you're exchanging with your friends, and what you want to do that night," he said in an interview, and just then co-founder Rick White interjects, "That's all in Utah."

Under the radar • That back and forth between the two — they're like the yin and the yang, White says — might just be one of the other driving forces behind Fusion-io. The company is still a bit under the radar in its home state despite its market capitalization of $2.56 billion, sixth among publicly traded companies with headquarters in Utah.

Fusion-io makes solid-state storage drives for servers, the large-capacity computers that work together in banks called clouds that are powering a growing number of company operations. Solid state means their drives are made with small but high-capacity flash computer chips such as those used in digital cameras, mobile phones, iPods and other such devices.

For 50 years, computer storage has been on hard-disk drives that spin as they store and retrieve data for delivery to a processor.

Disk drives have gotten cheaper and are able to store vast amounts of data, and their cost has been going down and down. But as computing speeds have blown up, the speed at which data can be retrieved from disk drives has not nearly kept pace. Hard-disk drives were a thousand times faster than older tape drives, said Flynn.

"The problem," he added, "is that processors are now a million times faster," meaning they are waiting idle while disk drives retrieve and deliver data, reducing efficiency and speed.

That was the opening through which Fusion-io has moved, one also made possible by the production of smaller, bigger-capacity flash storage chips to meet the demand driven by iPods and other consumer devices.

But really, Fusion-io began with an idea — a bad one as was quickly clear.

Hatching the idea • Flynn and White are disparate personalities whose coming together proved highly successful despite a rocky start.

Flynn grew up in Alabama and became a computer nerd with an early Commodore 64. While still in high school, he went to work at Computer Science Corp., helping build missile guidance systems. Computer graphics drew him to Utah, where attended Brigham Young University and married a Utah girl.

Post-BYU, Flynn worked for Oracle, then a spinoff company and finally Linux Network, where he was chief architect for the company's supercomputers.

Flynn is the quieter of the two, more reflective and precise. White is loud, funny and gregarious.

The latter's interest in computers came from an Apple model bought for him at 13 by his father, who was suffering from a terminal illness. White said he loved showing off the machine, and that led him to a career in marketing and sales for technology companies. He also started several of his own.

White grew up in California and came to Utah as part of a sales job.

Flynn and White met when they were contributing to an open-source project. They discussed an idea that would line up small mobile computers and flash memory to create a tiny supercomputer.

"And it took him about 10 seconds to analyze why it was such a horrible idea," said White, namely that such a device would not do math, and supercomputers have to do math.

But, according to White, by the next day Flynn came up with the idea of lining up chips to make storage devices.

"We started thinking about it, and the next thing you know we're talking each other into starting a company," said White.

Off with a fizzle • Fusion-io, though, had two tough years at the beginning, one of which meant convincing its engineers to go without pay for 11 months in return for stock (now quite valuable —shares closed on the company's first day of trading, June 9, 2011, at $22.50 and on Friday at $28.44). They also came to the frustrating conclusion they had to do their own manufacturing, as well as create their own software.

Then, as the company introduced itself to the world in 2007, the very same day computer storage giant EMC Corp. announced it was putting solid-state technology into its existing hard-disk storage systems used by many large customers.

In recounting this story of a shaky startup versus an established giant, Flynn and White point to a book, "The Innovators Dilemma," by Clayton M. Christensen. The author writes about how established companies with a revenue flow from older technologies can be "disrupted" by upstarts that have no need to protect existing revenue streams and, therefore, can create innovative products that push out older ones.

Sure enough, EMC stuck its new solid-state devices into cabinets holding disk drives in order to try to improve performance while protecting revenue. Flynn and White created small cards with flash chips managed by a controller and software that could be plugged into a server.

The advantages of that approach are now obvious in terms of speed, cost, capacity and energy use, the two said.

"The first product we launched, that one little card had the same performance as a thousand hard-disk drives all running together," said White. "It was five refrigerator-[sized racks] of disk drives in these very expensive computer systems replaced by this one card."

When deployed in data centers, the company's storage devices can lower electrical use by about 20 percent and cost perhaps one-tenth as much as a rack of solid disk drives. Data-delivery times can fall from thousands of a second to millionths of a second, said Flynn.

"The amount of efficiency you reap, the amount of computing output you can get done, is immense," he said.

Capital infusion • The company also caught the attention of venture capital companies, including Sequoia Capital, one of the legendary firms in Silicon Valley. Making a deal with Sequoia is every startup's dream, said White, but the firm required that Fusion-io move to California in order to get funding.

Flynn and White said no, kept the company in Utah and instead got a capital infusion from NEA, or New Enterprise Associates.

Now, with cloud computing surging and the demand for speed, lower costs and lower energy use rising, Fusion-io might be poised to sustain high growth for a number of years. Flynn believes annual revenue in the industry, now at about $1 billion, will grow to $40 billion to $50 billion.

Because of potential computing productivity gains of 15 percent to 20 percent and the other advantages of flash storage, venture capital is pouring into the sector, said Dave Floyer, a founder of Wikibon, a Web-based organization that shares technology research and advice among its members. He said Fusion-io is well-positioned to compete.

"Being well-positioned and success are two different things," said Floyer. "It's a tough road and there's going to be a lot of competition in that area."

But he pointed to a announcement earlier this year from Fusion-io that it had used eight Hewlett-Packard servers and eight of its own memory cards to break a computing barrier of 1 billion input and output operations per second.

Previously, "it would require thousands and thousands of servers to do that, and a huge amount of money," Floyer said.

The company employs about 300 to 400 people in Utah and another 200 worldwide. It reported $158 million in revenue in the last half of 2011, up $100 million from 2010.

"We were lucky enough to be at the right place at the right time when there was a sea change going on, away from mechanical-based disk drives to this solid-state storage technology," said Flynn.

With IM Flash chips made from silicon wafers, it is part of the next wave of the computing revolution.

"We're turning from [silicon] sand," said Flynn, then White interjected, "all the way into information."

"From sand to data in Utah," said White. "I like that."

tharvey@sltrib.comTwitter: @TomHarveySltrib #utahtech —

How Fusion-io stacks up

The largest market capitalization among publicly traded companies based in Utah*:

1. Zions Bancorp. • $3.96 billion

2. Nu Skin International • $3.66 billion

3. Questar • $3.43 billion

4. Huntsman Chemical • $3.33 billion

5. Extra Space Storage • $2.73 billion

6. Fusion-io • $2.56 billion

* As of March 30. The Woz comes to Fusion-io

Steve Wozniak, one of the creators of Apple along with Steve Jobs, is chief science officer of Fusion-io. Co-founder Rick White said it was David Bradford, the former Novell executive who served as an interim CEO at Fusion-io, who made the connection between the Utah-based startup and the computing legend.

Bradford met Wozniak at a conference and then arranged a meeting with Fusion-io co-founder David Flynn and White in fall of 2008 in Los Gatos, Calif., where they hoped to convince the computer legend to join their advisory board, according to White.

Wozniak came to the restaurant on a Segway — the two-wheeled electric personal vehicles — and then proceeded to drill them on the technology and their marketing strategy, White said.

"So Steve said at the end of the lunch this is very interesting but I don't know that I'm interested in your advisory board," said White. "We said, 'Well we understand.' He said, 'Well, no, I want a more active role.' "

After flying back to Salt Lake City and considering what they might do, the Fusion-io founders offered Wozniak the post of chief scientist.

"He said, 'Done. My first full-time job since Apple,' " Smith said.