This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2011, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

If the Olsens of Utah County are any indication, the dysfunction among the nation's banks who service mortgages runs long and deep.

Three members of the same family have experienced mounting frustrations, dislocations and months of stress in trying to renegotiate loans on their homes after they had financial setbacks. Each had bought or constructed homes near the height of the housing market only to see their finances and homeownership threatened for a variety of reasons in the economic meltdown.

Each at some point made decisions about their loans and their dealings with the banks out of frustration or naivete about negotiating with large and, based on their experiences, what appears to be poorly administered processes at the institutions.

Thousands of Utahns may have experienced many of the same problems in trying to modify loans taken out during the boom, a frenzied run-up in housing prices that according to a congressional commission was created in part by the very entities with whom they are now trying to negotiate. Dozens of lawsuits document similar frustrations.

—

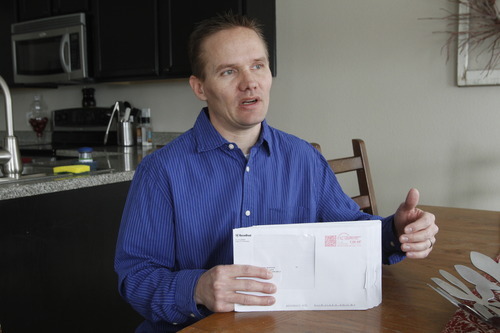

In the beginning • Mark Olsen said he bought a home for his family in a new subdivision of Lehi in 2007 for $300,000, putting up $60,000 as a down payment and for fees. His loan from Countrywide Home Loans came with initially low monthly payments that were to rise dramatically in five years, at which time he believed he could refinance.

But after losing his job and trying to start a home-based Internet marketing company in 2008, Olsen ran into financial problems and knew he couldn't make his full mortgage payment. So he called Bank of America, which had acquired Countrywide after it went bust, to try to make new arrangements.

That, he says now, was a mistake.

The call initiated a back and forth between Olsen and BofA representatives over his desire to lower the principal and the size of payments.

"Every time they would say something like, 'Yeah, let's do something to help you,' " he said. "But every time they would jack the payments up higher."

Then, in the midst of negotiations, a foreclosure notice was tacked to his front door. The family decided to move out of its now significantly devalued home and try to do a short sale, in which a lender agrees to accept less than is owed on a mortgage.

Despite what Olsen said were several significant offers, BofA never agreed to a short sale. At the suggestion of the bank, the family moved back in with the prospect of qualifying for a loan modification.

"They gave us the hope we were going to be here long term," Olsen said.

As the family was putting away silverware, the Olsens found a FedEx package with a loan-modification agreement that had been sent to the vacant house months after they had moved out, Olsen said. Another round of negotiations faltered, and on Feb. 15 a new foreclosure notice appeared on their door.

So Olsen called BofA, "and they said there's no sale date on your house. I said, 'Really, I have a notice of trustee sale set for March 19, and I've been trying for seven months, plus the three-year span, to get something going for us.' "

That led to more discussions and then on a recent Saturday a phone call from a bank vice president who asked for copies of paperwork but appeared to be unaware that a senior negotiator had also been working with them.

Finally, this. Olsen said he received details of a new offer — a 40-year loan for $362,000 on a home he said is worth around $220,000, though a senior vice president recently got involved.

—

'Contagion and crisis' • Amid these years of negotiations by Olsen and many others, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission established by Congress in 2009 has determined that entities such as large banks and Countrywide were largely responsible for the creation of the real estate bubble and its eventual burst.

Lenders loosened loan standards and sold subprime mortgages — such as adjustable-rate mortgages where payments ballooned after a few years, or loans with interest-only payments — to many people who either could not afford them or whose credit worthiness could not bear the risk, the commission said in a recent report. The loans were then securitized by bundling them together and selling them to investors around the world.

From 2001 to 2007, national mortgage debt nearly doubled, and the amount of mortgage debt per household rose more than 63 percent, from $91,5600 to $149,500, the commission said.

"Lenders made loans that they knew borrowers could not afford and that could cause massive losses to investors in mortgage securities," the report said.

It concluded that "collapsing mortgage-lending standards and the mortgage securitization pipeline lit and spread the flame of contagion and crisis."

—

Frustration abounds • Marshall Bare of Saratoga Springs is Mark Olsen's brother-in-law, and he got caught up in the inferno, too. Self-employed as an Internet programmer, he said that in September 2009 he had a "difficult financial month" that led to issues with his mortgage.

"I'd always heard it was better to communicate with the bank."

Bare said Wells Fargo representatives told him they would not agree to a partial payment and then put him on a path toward the Obama administration's Home Affordable Modification Program.

He said he made three monthly payments, even though "I didn't want to be on the Obama modification because I didn't believe in anything he does."

After months of frustrated communication, he said last June Wells Fargo insisted that within a week he had to submit a large amount of documentation. He missed the deadline, saying the bank had taken nine months to get to that point and he wanted more time.

"I guess it doesn't work that way," said Bare. "I didn't get it done in time and they said because of that you're kicked off the program. You now owe us $7,000, which I didn't have."

In December, a trustee sale was set, but Bare was able to get a postponement.

"They finally said, 'OK, we'll do that if you can make the full original payment for three months,' " he said. "Now the full amount to pay my debt and all the late fees they tack on is $14,000."

Bare said he has been unable to pay the $14,000 and that talks have continued.

"I see that they are taking forever to get me a modification because I started in August and now it's six months later and they're saying it's going to be another three months and probably another six months," said Bare, who is still expected to continue to make payments in the original amount.

—

Finance barriers • The quagmire confronting Olsen and Bare should come as no surprise. As the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission concluded in its report: "The system that created millions of mortgages so efficiently has proven to be difficult to unwind. Its complexity has erected barriers to modifying mortgages so families can stay in their homes and has created further uncertainty about the health of the housing market and financial institutions."

Among those barriers are knowing who exactly holds the mortgage note. Mortgages were sold to pools of investors that could include hundreds of individuals and funds.

Howard Headlee, president of the Utah Bankers Association, recently said it is virtually impossible for homeowners trapped in a foreclosure process to try to renegotiate terms of their loans.

Note ownership is fractured and loan servicers who gather payments on their behalf are under contractual restrictions that make negotiations extremely difficult, he said.

He likened the process of renegotiating a loan with the actual owner of a mortgage note to "unscrambling an egg."

—

Agreement or not? • Melvin Olsen, father to Mark Olsen and father-in-law to Bare, knows that all too well. The Lindon resident is in a financial pickle for what he readily admits was a "stupid decision."

At the height of the real estate boom in 2007, he decided to finance the construction of an upscale house in the Deer Crest development at Deer Valley in hopes of selling it for a tidy profit.

Olsen said he couldn't get a loan from Countrywide for the lot he wanted but that it did extend a loan on his Lindon house, which had been free and clear of debt.

Then the dowturn hit and he could sell the spec house for the cost of construction but not for the amount of the loan on his house. His retirement income was not sufficient to cover the monthly payments.

So in August 2009, Olsen tried to get a loan modification from BofA.

By December he had reached an agreement and last March he started to make payments of $4,530 based on the modification agreement. Then a letter came saying his payments would increase to $5,060.

Olsen rescinded the loan-modification agreement and started negotiations anew. In August, Olsen said he was told a new deal had been approved at the vice president level but that the bank's legal department needed to sign off.

Then, he said, he received a notice of default and intent to sell his home unless he paid $26,363. The bank negotiator also cut off contact.

In December, after a letter to the CEO of BofA, Olsen said "things lit up" and he received a new modification proposal with a monthly payment for $2,511 for five years before it increased. He signed and sent it back.

He made a first payment. Then BofA sent him a statement showing he owed payments of $2,695, or $184 more a month than the modification agreement spelled out.

Olsen said he got mad and rescinded the second agreement.

"I would like to modify the loan but seek honesty from Bank of America," Olsen wrote to the institution. "Please send me a proposal you're willing to abide by. I expect the actual loan payments to match the amounts in the loan modification document."

Olsen said a negotiator did admit to errors in the loan agreement and that he would get a new one. On March 1, Olsen received a "new" package, but it carried the date Dec. 29, 2010, and was supposed to be effective Feb. 1, 2011 — and be sent back to the bank by Jan. 8.

Olsen believes BofA has failed to negotiate in good faith, but he still is trying to work out something.

"The banks need their comeuppance. They need to face the music, just like I need to face the music on my poor investment. I think the wrongs they have done are far worse than the wrongs the homeowners have done."

—

Banks respond • Chris Peterson, a University of Utah law professor and expert on legal questions surrounding foreclosures, said millions of people around the nation are in the same boat as the Olsens and Bare.

"Bank of America needs to do a better job of providing loan modifications to the families that need help and they need to use their more profitable lines of business to cross-subsidize that," said Peterson. "That's the obligation they have to the families but also to the investors that own the securities that are drawn out of those mortgage loans."

In response to queries about the Olsens' experiences, a BofA spokeswoman said, "We apologize to our customers that have not experienced the level of service they have come to expect from Bank of America. We continue to dedicate unprecedented resources to improve that experience."

Jumana Bauwens also said the bank has completed more than 775,000 permanent loan modifications, including more than 100,000 through the Home Affordable Modification Program.

In an e-mail, she said the bank recently took steps to improve its modification and foreclosure practices, including opening customer assistance centers, establishing a case management process and addressing the confusion caused by modifications processes that continue, even though a sale is about to take place.

Wells Fargo spokesman Jason Menke said the bank was continuing to work with Bare "to explore options that would allow his family to remain in their home. Foreclosure remains an option of last resort, and we work to prevent it whenever possible."

Fines possible for banks

The largest mortgage firms in the U.S. — Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co. — say they could face action by federal regulators. › E2