This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2014, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Taylorsville • Angela Malae never has liked math.

In high school, "I just did what I needed to pass it and then got out," she said. Now the 31-year-old is laboring through algebra again after returning to Salt Lake Community College to become a physical therapist. She's trying to teach her children, ages 7 and 8, to stick with arithmetic.

"I want to make sure they focus on math and keep going," she said. "I want them to enjoy the harder math classes ... to be excited to go in and make it, and not have anything hold them back."

Malae likes a new recommendation for college-bound high school students from the Utah System of Higher Education that they take four years of math instead of the required three. The guidelines represent a more vocal approach by higher education leaders who hope to boost the state's six-year college graduation rates, which a recent report ranked lowest in the country.

The rates are low partly because too many Utah high school students are unprepared for higher education. Last year, an analysis found 62 percent of graduates who had taken the ACT college placement test weren't ready for college math.

"Many would think that it's pretty seamless ... if you graduated from high school to be ready to move to college. But it's not necessarily so. There's a bit of a gap, particularly in the math area," said Dave Buhler, commissioner of higher education. "Hopefully it'll be a public service we can start to get the word out there, 'Here's what you can do to be really prepared for college.' "

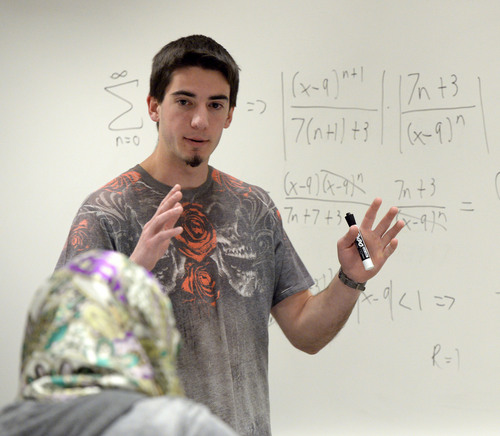

Those who aren't ready for college math usually end up in a remedial or developmental course such as the one Malae is taking. Those courses have come under fire from groups such as Complete College America, which calls them "higher education's bridge to nowhere."

Designed to get students up to speed, the courses can instead be a "graveyard for people's expectations of graduating college," as Buhler has said, in part because students have to pay tuition even though they aren't getting college credit.

And most students placed in remediation don't finish school. According to Complete College America, barely a third of students complete a bachelor's degree within six years. Among community college students that number is even lower — just one in 10 finish a degree in two years.

Graduation rates are a concern in Utah, where the number of educated workers may not be growing fast enough to meet job market demands. Researchers estimate that in the next six years, some 66 percent of Utah jobs will require at least a postsecondary certificate. About 45 percent of residents have that education now.

"Any science, engineering-type job, there are so many jobs out there," said Cami Barlow, a 25-year-old SLCC student. But "you can't fill those jobs because people are scared of math."

Barlow hated the subject so much in high school she wasn't initially going to study science. But a few good teachers and near-daily tutoring at the SLCC math lab changed her mind. She's now a geology major hoping to work in the oil and gas industry.

Barlow's study partner on a recent day at the math lab, 33-year-old engineering major Nile Brewer, said he was more interested in sports than studies as a teen.

"School wasn't a priority, which I still regret because other people have a jump on me," he said. Now, "I think math is so fundamental, the more of it you can get out of the way the better."

More math in high school could help more students avoid remediation and get started on their degrees right away.

"There's a lot of research that shows for every year students [don't study] math, they lose at least a year and sometimes more," said Diana Suddreth with the Utah State Office of Education.

But will high school students take four years of the subject if it's not required?

The Utah Board of Education considered making it mandatory in 2010 at the urging of technology business leaders, but some small school district officials said they didn't have enough teachers to staff the extra courses. Ultimately, the board decided the introduction of the Common Core standards was enough change.

Since then, the idea hasn't come up again, Suddreth said.

The new recommendations, she said, can guide class decisions for college-bound teens — and, perhaps more important, inform parents such as Malae, she said.

"When you're 17, you can't understand the importance of some of the decisions you're making," Suddreth said. "[Some] people think math isn't as important because they either didn't like it or didn't use it. ... The world that students are entering today is different from the world I entered into where you didn't even need algebra."

Twitter: @lwhitehurst