This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Jay Henry looks forward to the day he no longer has to cover up air vents with cardboard.

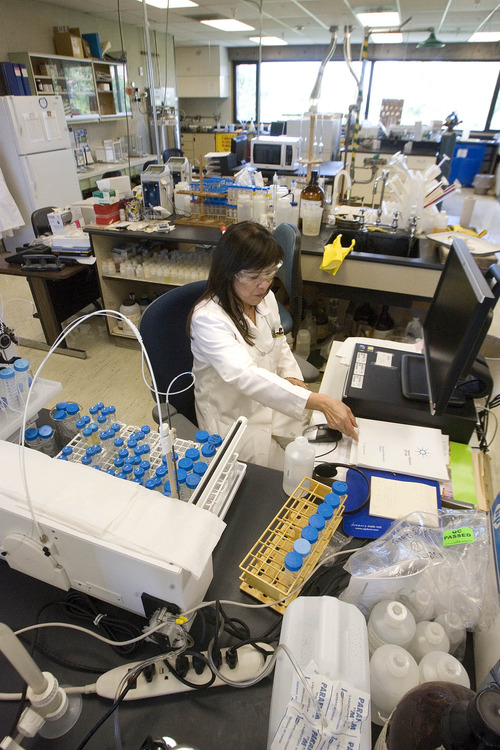

The patchwork is not only meant to help control temperature in an office never intended to be Henry's state crime laboratory, but it is also a precaution against the air suddenly kicking on, hard, and blowing a suspect's hair around the room.

Weston Judd, director of the Utah Department of Agriculture and Food labs, faces similar issues in his offices-turned-labs.

A few miles away, Henry's partner in crime solving, state medical examiner Todd Grey, looks forward to a bigger morgue. The spaces are cramped to their limit — not only for his employees, but for the dead, too. In worst-case scenarios, they have to put two bodies in a space meant for one.

"You don't want to be treating the [deceased]as just lumber," Grey said, "both for their own dignity and for their relatives."

The burdened scientists agree: They could go for better space — and more of it.

Relief may be in store, and soon. Late last month, Henry, Judd and Grey met with an architecture firm to design a big, modern laboratory for all of them, to solve crimes, tend to the dead and make sure products are labeled honestly and made safely.

The Utah Legislature approved funding this past session for the three agencies to pursue a design, which they have spent the summer doing. Henry added that he is keeping his fingers crossed that once they settle on a proposal in time for the next legislative session, lawmakers will approve funding for its construction. The bill is estimated at $35.6 million.

The three-story building in the works, near 4500 South 2700 West in Taylorsville, would house the state medical examiner and some crime labs on the first floor, the rest of the crime lab on the second and the agriculture department on the third. The building is actually the second half of the Unified State Lab project, which broke ground May 13, 2008. The first building primarily contains labs for the Utah Department of Health.

Henry looks forward to the much more efficient teamwork that will come from putting the crime lab and the medical examiner's office under the same roof. "[We'll] be able to speak with the doctors about how the person died and have our scientists work with them, with the [police] investigators watching," Henry said. "It just adds to the whole efficiency of funding, combining all these facilities."

The new building also would unify Henry's scientists with the ballistics-testing group, which for now has had to work off-site. The crime lab's chemical storage room is also too small, there's no dedicated training and conference space, and its information technology is dated. If a fire broke out, the sprinkler system would damage its expensive equipment; a new fire suppression system would not.

Judd and Grey recognize that Henry and his people have it worse, but the two have their fair share of concerns. Judd, for one, would not call his division's retrofitted office space ideal.

"It's not optimal for laboratory work. The building [at 350 N. Redwood Road] is getting older, like drafts and things like that," Judd said. "A new building would improve the overall laboratory working areas, like ventilation with fume hoods."

And Grey's morgue is quickly running out of space. He and his staff moved into their building at the University of Utah in 1991. The state population — and, naturally, the dead — have shot up about 30 percent since then.

"Our workload has exploded," Grey said.

The usual spaces filled, they have been forced to store bodies on racks, which is cumbersome since some of them are 8 feet up. When that fills up, Grey said, they have to store two bodies in a space meant for one.

More bodies also require more autopsy staff, and at this point six of them have to share a 10-foot-by-15-foot office space. The new building hopefully will double the dead-body capacity from 30 to 60, and provide individual space for up to 15 staffers, Grey said.

"That will be a big improvement [for] storage of supplies and equipment," he said. "Right now, they are jammed into whatever nook and cranny we can find."

Whenever the new building is finished, Henry hopes to open his labs to public tours for a week, the same way Salt Lake City police did with its new Public Safety Building.

Funding for the lab is a priority in Gov. Gary Herbert's recommended budget for 2014, an encouraging sign. The budget recommends transferring some of the $44.7 million the state saves from reduced Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program caseloads to help pay for the construction.

For several years, the new lab has been a top priority for the three agencies that would call it home, Judd said. The agencies had asked to start the project session after session, and money to begin finally coming through last spring was encouraging, Judd said.

"I'm cautiously optimistic," he said.

Twitter: @mikeypanda —

Crime lab ramping up

Funding constraints have reduced the staff during the past few years, creating long delays in a lab that processes about 10,000 pieces of evidence every year. Ideally, the lab would turn an analysis report in three weeks. But the average completion time has tripled for crimes that don't have the priority of a violent felony.

In spring, legislators granted the lab's request for two more DNA analysts to handle the mounting evidence. The new hires are well educated, but the on-job training takes a long time to get them to a level where they are "really comfortable" with case work — especially more complicated cases, like a knife fight with a lot of blood splatter patterns to interpret, said lab director Jay Henry.

"It's a challenge because it's complicated and time-consuming, and there is not enough of us right now until we get everybody online," Henry said. "It will take a while for us to ramp up."

A big contributor to the growing mountain of evidence is the lab's improved technology. Devices that collect DNA can pull a lot more DNA than they used to — a blessing and a curse.

"Everybody says that's great; it can detect perhaps the perpetrator, but the [downside] of that is you are able to detect anybody else who handled the item," Henry said. "We're spending more time analyzing samples."

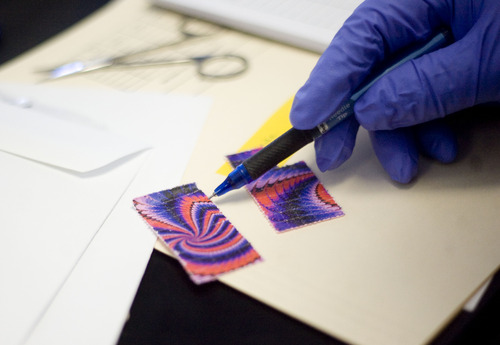

Still, the lab has successes to celebrate amid its challenges. Improved technology helps the lab workers keep up with the synthetic drug spice faster than they used to. The drug hit the Utah market in a big way in 2011, and even through 2012, the lab workers were struggling to keep up with constantly changing formulas. Now they can decipher the drug's makeup quickly and pass that information on to lawmakers to ban the ingredients as soon as the legislative schedule allows.

There is also the lab's DNA database, collected mostly from convicts, which leads to more solved cases. Henry remembers a time when it was a big deal to get a match in the database twice a year. Now, the hits come in each week. The lab is hitting a ton of singles now — it takes a lot, like a hit on a 40-year-old cold case, to feel that grand-slam rush again, Henry said. To date, the database has solved more than 300 cases.