This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

Bruce Norris' "Clybourne Park" contains so many scenes designed to self-destruct at the slightest touch, and treats its characters so mercilessly that the prospect of commenting on it at all induces a stark, creeping dread on the skin of any self-respecting theater critic.

And surely that's part of Norris' point. Taking sides with almost anyone on display — from the well-meaning but condescending Bev in Act I, to the patient but ultimately volatile Lena in Act II — means subjecting your own smug self-respect to Norris' sharp, churning blades of bitter sarcasm.

"Clybourne Park" plants its feet firmly in a rhetorical neighborhood where everyone speaks whole or partial truths at some time, but most of the time they're all entirely or partially wrong. It seemingly mocks any naive concepts we might hold about "importance" when we sit down to watch a play advertised in advance as dealing with such meaty issues as race, class and society. That's what happens when you win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, as Norris did for this particular script in 2011. Consider yourself warned.

The play's singular invention is that it bolts straight from the starting gate of Lorraine Hansberry's classic 1959 drama "A Raisin in the Sun." Starting in the white household of Bev (Celeste Ciulla) and Russ (David Manis), who've just sold their middle-class American property to Hansberry's Younger family, Norris creates brilliant characters from whole cloth, even as he reintroduces us to Karl Linder (Brian Normoyle), the insistent but simpering neighborhood council representative who warned the Younger family against moving into a white neighborhood, but lost.

But where Hansberry was more interested in revealing the bravery and tenacity of black people in the face of racism, Norris makes it clear his concerns aren't so specific. Still recovering from the loss of their son Kenneth after the Korean War, Russ takes little interest in the fact that selling his family home to a black family might help or harm anyone's fortunes. What matters most in a domicile is that you may hear only what you want.

"You can't live in a principle. You live in a house," Linder reminds him in words repeated in Act II. Russ knows as well, showing the door to anyone who dares take up the topic of his son's demise,including Linder and his deaf, pregnant wife Betsy (Tarah Flanagan).

Meanwhile, wife Bev muses over the geographic origins of words including Neapolitan. It's all a preamble to extended musing between characters about how choices of diet and recreation define us. "It's nice, in a way, to know we all have our place," Bev says.

The play's second act jets forward to 2009, 50 years later, reprising many of the first act's same themes and ideas, but in an altogether different, more confrontational tone. The battlefield, however, is slightly altered. Where red-lining and racial integration set the terms in 1959, this time the concern is a neighborhood's historic character and creeping gentrification. Even with pages of carefully defined zoning code to guide Lindsey (Flanagan in her second role) and Steve (Normoyle, also in second role) through a real-estate transaction in which they hope to demolish the home for new construction, everyone involved strays from their course into tense, often hilarious, bickering.

Pioneer Theatre Company's production under the direction of Timothy Douglas is tart, prickly and moves at a tempo expertly timed to let us revel in its energy, even as it makes just enough room for the audience to exhale in contemplation, or laugh out loud.

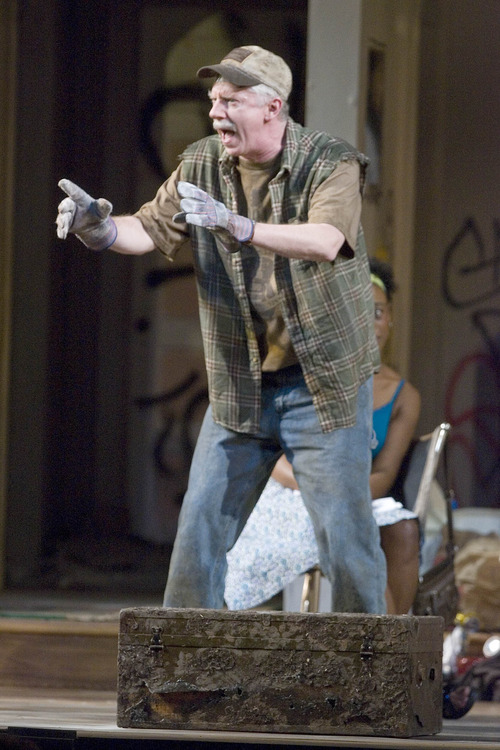

While hard to single out a single cast member in an ensemble that flows and stalls through all the right notes of this jagged script, Manis' portrayal of Russ stands near the play's center, if not its heart.

The triumph of "Clybourne Park" isn't the way it does, or does not, deal with issues of race, territory and class. It's instead the subtle line Norris draws from the heart of an aching father to a graceful coda at play's end in which the overlooked tragedy binding the play's two acts is revealed. Anyone can bicker over hurt feelings and historical injustices, the plays seems to say. Far more rare is the careful eye that sees tragedy coming before it hits, and after which we might at last find the opportunity to inch forward.

Twitter:@Artsalt

Facebook.com/fulton.ben —

'Clybourne Park'

Pioneer Theatre Company presents Bruce Norris' award-winning follow-up to Lorraine Hansberry's classic "A Raisin in the Sun."

When » Feb. 15-March 2. Mondays-Thursdays, 7:30 p.m.; Fridays, 8 p.m.; Saturdays, 2 and 8 p.m.

Where » Simmons Pioneer Memorial Theatre, 300 S. 1400 East, University of Utah campus, Salt Lake City

Tickets » $25-$44; at 801-581-6961 or pioneertheatre.org.

Bottom line • A robust, finely rendered drama by Pioneer Theatre Company about all-American anxieties that bites you in the conscience when you least expect it. Two hours and 10 minutes with one 15-minute intermission.