This is an archived article that was published on sltrib.com in 2013, and information in the article may be outdated. It is provided only for personal research purposes and may not be reprinted.

The most intriguing work on display as part of the Utah Museum of Fine Arts' latest exhibit has no artist's name on the lower right-hand corner of its frame.

As a result, we know no backstory about the artist's life, motivations or unique methods. All that's left to contemplate is the painting itself: the stark beauty of a turquoise sky, the rising cloud that splits its horizon, and a lone American Indian atop a hill, sitting next to his horse, there to behold it all.

It's tempting to view this one image as if it informed all the works included in "Bierstadt to Warhol: American Indians in the West." That's because the painting's title, "What an Indian Thinks," plays thematic flip-side to the exhibit's wider concerns of cultural identity, deconstruction of stereotypes and the appropriation of images from outside native circles.

"We took a large view for this exhibit," said Donna Poulton, curator of art of Utah and the West for UMFA, and also curator of the exhibit. "They're what you might call 'the big themes of art.' And we wanted to do all this in a respectful, educational way."

The exhibit, which hangs Feb. 15 through Aug. 11, is as impressive and dynamic as it is thorough in its examination of how indigenous peoples of the American West have been recorded on canvas and sculpture. It encompasses almost every school of visual art, from realism to pop art, from the early 20th century onward.

The exhibit opens with sweeping portraits of German-American painter Albert Bierstadt, English-American painter Thomas Moran and Utah's own Minerva Teichert. While the quality of these works is never in doubt, their veracity sometimes is. As Poulton points out, the viewer is left to consider whether some of the early representations of American Indians were idealized, or even imagined, rather than rendered with an eye toward reality.

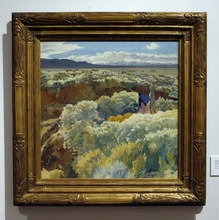

That's especially true regarding the artists trained in Paris- and German-based schools, who traveled abroad to capture images of the American Indians of Taos, N.M. Compared with other tribes and bands, the Taos-area Indians escaped the nation's westward expansion relatively unscathed. Often, as exemplified by Ernest Martin Henning's 1925 work "Indian Horsemen," they produced work more remarkable for the way the natural world was captured.

"They weren't out to exploit," Poulton said. "They were out to find the European ideals of truth and beauty in a people who'd never really been recorded in art."

The more the exhibit progresses through time, the more intrepid and risk-taking the art becomes. Any exhibit about the image of American Indians in art would have been remiss without the inclusion of American Indian artists themselves. "Bierstadt to Warhol" includes several, most notably the vivid works of Navajo artist Shonto Begay.

"My Grandfather's Funeral" depicts a Navajo boy gathering butterflies under a sky pulsing with cosmic energy, the procession in the background. "Helpless" conveys the despair of alcoholism, seen after opening the door into a room of intoxicated men strewn on the floor. The observer's shadow reflected in the light of the room is "a reminder to himself of a path he might have taken." Begay will open the exhibition with a Feb. 15, 6 p.m. artist talk at the museum.

The exhibit's biggest draw may prove to be the screen prints by Andy Warhol — "Sitting Bull" and "Geronimo" from the 1986 "Cowboys and Indians" series — plus Roy Lichtenstein's enigmatic woodcut "American Indian Theme IV." All three play on the ideas of American Indians and native iconography as celebrities and graphic symbols on par with Marilyn Monroe or a soft-drink logo.

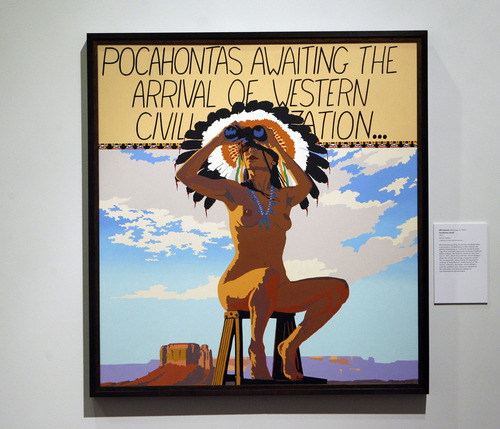

The one work standing as "the big elephant in the room," as Poulton describes it, is American artist Bill Schenck's "Pocahontas Awaits." Deliberately provocative from every angle, the 2012 oil-on-canvas painting compacts almost every myth and anomaly held by white America regarding native culture.

Not stopping at depicting Pocahontas topless and ready for plunder, Schenck places the Virginia Indian in Monument Valley donning a Plains Indian headdress. She peers through binoculars blindfolded, as if she doesn't see what's coming. In a "coup de grâce" stroke of style, Schenck delivers it all in flat, paint-by-numbers style, as if condemning the formulaic way most American Indian culture is viewed.

"When you cross cultures to portray another beside your own, it's a whole different take," Poulton said. "There's an unconscious layer of interpretation that takes place. [Schenck's painting] is a play on stereotypes and clichés so deep, you almost don't know where to begin."

Twitter: @Artsalt

Facebook.com/fulton.ben —

'Bierstadt to Warhol: American Indians in the West'

When • Exhibit hangs through Aug. 11. Museum hours are Tuesdays, 10 a.m.-5 p.m.; Wednesdays 10 a.m.-8 p.m.; Thursdays and Fridays, 10 a.m.-5 p.m.; Saturdays and Sundays, 11 a.m.-5 p.m.

Where • Marcia and John Price Museum Building, 410 Campus Center Drive, University of Utah campus, Salt Lake City.

Tickets • $5 for youth and seniors, $7 for adults. Free for U. students, faculty and staff.

More • Information at 801-581-7332; free admission on the first Wednesday and third Saturday of each month.

Artist's talk • Navajo artist Shonto Begay will offer a free lecture at 6 p.m. Friday, Feb. 15.